Though, ‘Overshoot’, is ostensibly a book about biophysical limits, the theme that runs through it is about the human propensity for denying obvious facts: Our ability to deceive not only others, but more importantly, ourselves.

Though, ‘Overshoot’, is ostensibly a book about biophysical limits, the theme that runs through it is about the human propensity for denying obvious facts: Our ability to deceive not only others, but more importantly, ourselves.

As with the first review in this four-part miniseries, ‘Farewell to Growth’ (2007), any book that posits the ‘end of affluence’ will inevitably attract the misanthrope, and their arch-enemy, the Cornucopian.

There’s a lovely exchange from one of the more comical ‘X-Files’ episodes that’s very descriptive:

“I wanna be abducted by aliens.”

“Why, whatever for?”

“…I just wanna be taken away into some place where I don’t have to worry about finding a job.”

Those who celebrate the book are as equally interesting as those who hate it: Celebrating the ‘end of society’ can be just as escapist as the cult-like belief that ‘technology will save us’; yet, as Catton describes, both misanthropy and Cornucopianism are a means of denying the demonstrable trends unfolding before our eyes.

Catton summarises the scope of the book in the Preface:

“In a future that is as unavoidable as it will be unwelcome, survival and sanity may depend upon our ability to cherish rather than to disparage the concept of human dignity… I have tried to show the real nature of humanity’s predicament not because understanding its nature will enable us to escape it, but because if we do not understand it we shall continue to act and react in ways that make it worse.”

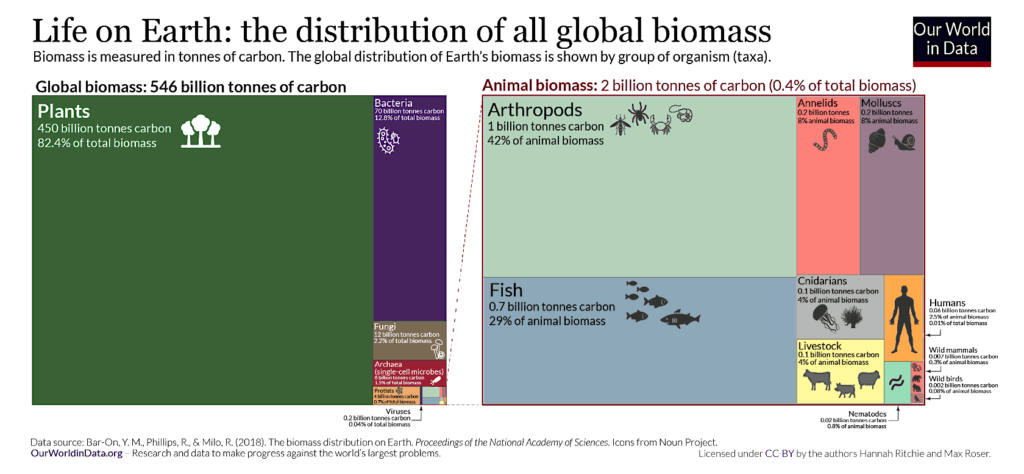

Click for a larger version of this graphic

That’s why this book has as many ‘haters’ as it does devotees: It attacks people’s ‘cult-like’ belief in the innovative power of technology; and disturbs the ‘comfortable classes’ by reminding them of the impermanence of those comforts.

As Catton says:

“The belief held that great technological breakthroughs would inevitably occur in the near future, and would enable man to continue indefinitely expanding the world’s human carrying capacity. This was a mere faith in a faith, like stock-market speculation; it had no firmer basis than naive statistical extrapolation… Such a faith overlooked the fact that man’s ostensible ‘enlargement’ of the world’s productivity in the past had mainly consisted of successive diversions of the world’s life-supporting processes from use by other species to use by man. It failed to see that ‘progress’ must stop when all divertable resources have been diverted.”

As demonstrated by that quote, the book touches upon one of the most sensitive issues at the heart of the contemporary ‘culture war’: The idea that the ‘power’ and ‘greatness’ exhibited by Western society is based not upon the innate superiority of Western culture, but their historic expansion, take-over, and expropriation of the resources of other cultures.

That’s made explicit where Catton says:

“Invading and usurping lands already occupied by others was essentially what mankind had been doing ever since first becoming human. Each enlargement of carrying capacity… consisted essentially of diverting some fraction of the earth’s life-supporting capacity… to supporting our kind. As the expanding generations replaced each other, Homo sapiens took over more and more of the surface of this planet, essentially at the expense of its other inhabitants. At first those displaced were creatures with teeth and claws instead of tools, with scales or feathers or fur instead of clothes.”

The precise statistical basis for this argument was fairly sketchy in 1980. It’s the way the book creates a mental framework to interpret humanity’s dynamic relationship to the Earth that’s insightful – and which spurred research to fill these knowledge gaps.

‘Humans make up just 0.01% of Earth’s life – what’s the rest?’

The book introduces terms which define the boundaries of our ‘development problem’, and our inability to accept and deal with those issues: ‘Take-over’, ‘carrying capacity’, ‘trade acreage’, ‘cosmeticism’, ‘energy slaves’, ‘drawdown’, ‘exceptionalism’ – and many more.

As Catton says:

“The advancement of knowledge increases man’s ability to manage the forces of nature to his own ends. Developments of human organisation also raise our power to extract abundance from a fixed quantity of land. The carrying capacity of a continent is thus neither fixed nor easy to calculate – but that does not make it infinite. For a given quantity of land… the population that can be supported must vary inversely with the standard of living. During an era of increasing productivity this inverse relationship between population density and human well-being seems not to apply. In due course, it will.”

There’s so much I’d love to review here, but that’s not going to fit into a five minute summary. To end, I believe that Catton is making a positive argument for change, rather than misanthropic framework to label our predicament:

“The paramount need of post-exuberant humanity is to remain human in the face of dehumanising pressures. To do this we must learn somehow to base exuberance of spirit upon something more lasting than the expansive living that sustained it in the recent past. But, as if we were driving a car that has become stuck on a muddy road, we feel an urge to bear down harder than ever on the accelerator and to spin our wheels vigorously in an effort to power ourselves out of the quagmire. This reflex will only dig us in deeper. We have arrived at a point in history where counter-intuitive thoughtways are essential.”

The value of ‘Overshoot’ is not simply as a warning for humanity’s ecological fate. It provides a mental framework for how we define our relationship to the issue, and map that to a practical basis for change. That, ultimately, defines the imperative for change more clearly than just the statistics for why change is necessary.

Afterthoughts on ‘Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change’

This is the second of four related reviews, the relevance of which, I’m almost certain, will escape the perceptions of quite a few – and annoy a few more who do accept the underlying theme of this series. Therefore, I think it’s worth being clear why I’m grouping these works together, which is something I’ll develop in the ‘afterthoughts’ section of each review.

Put simply, ‘Overshoot’ is a book on the sociology of economic collapse: Of how societies choose to deal (or not) with the ‘overshoot’ of the human economy; and, as with any species that exceeds its carrying capacity, how collapse must be the inevitable result of ecological overshoot.

However, whereas ‘natural’ species do not have the wherewithal to control their population collapse, the ability of human society to anticipate, study, and understand the nature of ecological collapse, gives us a unique ability to change that outcome… if we collectively choose to do so.

Therein lies the problem – which is what this book describe

Contrary to the popular dialogue – again, the product of the ‘magical thinking’ which inherently plagues complex human systems – The Enlightenment did not end the role of mystical or religious belief in the conduct of human affairs. Instead, the role of mystical thinking itself became ‘reductive’, ‘technological’, creating narratives that, while settling for human material satisfaction, cannot be substantiated through objective method.

For example: The ‘Laws of Physics’ state that the environment is finite, and that entropy can only increase; yet at the same time, the basic principle at work in contemporary economics is that economic growth can, on average, continue forever.)

In general, this book is not well-known enough to receive the ire of the Cornucopian lobby on a regular basis; certainly, not to the level of the bile directed towards ‘Silent Spring’ or ‘The Limits to Growth’. From my reading of both supportive and critical comments, though, I think there’s a disconnect between how people perceive: Catton’s presentation of the physical collapse of the human system; versus his observations of how humans comprehend and react to the knowledge of this imminent collapse. It’s a subtle difference, but important in terms of Catton’s greater body of work, and the legacy he has created for us today.

To understand ‘Overshoot’, it’s worth reading the paper Catton co-authored the year before which defined the principles of ‘environmental sociology’. Or, as the Wikipedia page most helpfully summarises:

“Environmental sociology is the study of interactions between societies and their natural environment. The field emphasises the social factors that influence environmental resource management and cause environmental issues, the processes by which these environmental problems are socially constructed and define social issues, and societal responses to these problems.”

For me, this is the stumbling block I perceive many encounter when reading the book: It is not about the ecological processes of ‘overshoot’ and ‘collapse’ specifically; it is about us!, and how we collectively react to those issues.

At a time when the world seems incapable of addressing itself to the issue of climate change, ‘Overshoot’ provides a valuable framework to understand our predicament. For example: Simply swap ‘consumption’ for ‘emissions’, ‘tipping points’ for ‘overshoot’, and ‘climate breakdown’ for ‘collapse’, and book’s arguments easily map to the climate debate; and thus how the world is, but practically, is not, adapting to the objective ecological realities of climate breakdown.

The difficulty is, if you do transpose ‘Overshoot’ onto the ‘climate crisis’, the results are not exhilarating. That’s because – as a sociological work – you can see how the denial and deflection methods that ‘Overshoot’ outlines at length run throughout the climate change debate today; and more importantly, that addressing those obstacles has little to do with the technicalities of climate issues, and everything to do with the self-delusion, and short-term, magical thinking that plagues human reasoning.

Perhaps more critically, the way ‘Overshoot’ addresses ‘Cargo cultism’, or the belief that technology can insulate the individual from radical systemic change, can equally be seen as critical of the environmental movement itself. Environmentalism arose as a ‘deep ecological’ focus on the relationship of humans to their environment. Unfortunately, as the issue became adopted into mainstream society, that insightful focus was distorted by cultural forces into responses such as ‘green consumerism’ or ‘green technologies’ – which operate, as Catton outlines in the book, as a very effective distraction from the deep systemic change which is actually required.

For those who choose to read, ‘Overshoot’, I suggest that you keep this distinction in your mind: Between the ‘phenomena’ of ecological collapse; and the human interpretation of that phenomena. When the book is read as a description of how humans respond to existential threats, rather than how those threats evolve, Catton’s work provides a really useful set of tests and tools to pick-apart the environmental debate today.

Finally, to bring this full circle, a key part of interpreting ‘Overshoot’ is to understand how individuals relate to such complex issues in general. In particular, the seemingly unbridgeable gap between misanthropes and Cornucopians which I outlined at the beginning.

In practise, the problem is best defined in terms of how we quantify people’s responses across any issue, and whether we use a single, or multiple indicators to measure that.

For example, political beliefs are not simply a measurement of libertarianism verses authoritarianism; it’s also strongly influenced by a person’s views on state regulation versus market determinism, or social conservatism versus social freedom. Likewise, people’s response to ecological issues isn’t a simple metric for whether they deeply identify with nature, or with human progress; it is also mediated by their introvert versus extrovert nature, or their desire to practically create their lifestyle versus a willingness to passively consume – framed, inevitably, by that complex political belief system noted above.

How we solve the ecological crisis cannot be a ‘one size fits all’ approach. It has to engage with humans, ‘as they are’, rather than assuming that everyone will willingly be corralled into one strategy or another. In other words, we need a strategy for misanthropes, another for Cornucopians, and a more general set for everyone else.

The dominance of ‘magical’ economic or technocratic thinking restricts our options for change, and provides a powerful basis for the rejection or denial of facts – which Catton describes at length. It may be, to solve the many psycho-social obstacles Catton defines, and overcome the deep denial exhibited by many, that to achieve change quickly we need a parallel set of options. In reality, though, whatever the approach, unless people can accept that their cherished ‘normality’ is over, change will never be able to take place on a sufficiently prompt time-line to avoid the inevitable outcome of ecological overshoot.

Teaser photo credit: Photo by Max Felner on Unsplash