This is the final post of a three part series on the existential problem of degrowth in a world that still believes in perpetual economic growth. Part 1 was published on Resilience.org here, and Part 2 was published here.

If we’re not going to voluntarily enter an era of planned, controlled degrowth, what are we going to do instead? To answer that question, we need to return to a statement highlighted in Part 1 of this series:

As a general rule, deeply-held mental models are only abandoned when the pain they inflict finally outweighs the psychological comfort they provide.

As noted in Part 1, we do not abandon our deeply-held mental models easily. The point I want to make here is that we don’t abandon them when they start failing to explain a changing world. Rather, our first instinct is to deny the evidence and reaffirm the model: the world isn’t really changing at all. Our second instinct is to (grudgingly) acknowledge that the world is changing, but to call the change temporary, declaring that things will come back into alignment with the mental model eventually. As long as the gain exceeds the pain, these efforts at denial and delay will continue.

Only when the pain exceeds the gain — that is, when the pain is undeniably severe, universal, immediate, and with no end in sight — will the model finally be abandoned. By that point, of course, the world is in much worse shape than it would have been if our leaders had acted when the mental model first started failing. But sadly, that’s not how humans are wired and not how human societies operate. So here we are.

One of the ways the perpetual growth model distorts reality is that it doesn’t take resource depletion seriously (source. It assumes that supply can always be found, either through exploration or substitution, to match demand. It has to assume this, because if supply could run out, then growth could stop. But growth cannot stop (because the mental model says it can’t), so supply can never actually run out. As a consequence of this tautological logic, our leaders tend to focus on demand-side interventions to deal with the effects of climate change and resource depletion.

If we put these ideas together, we begin to see the broad outlines of how our future is likely to unfold.

What is involuntary degrowth going to look like?

This is the point where one traditionally quotes Hemingway from The Sun Also Rises:

“How do you go bankrupt”, Bill asked.

Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”

“Bankruptcy” is a very apt metaphor for our current situation. The word describes what happens when an individual’s “supply” can no longer meet their “demand”. A bankrupt individual is, in effect, in overshoot. And that is where our civilization is today. We quite literally don’t have the resources to pay the bills we have run up with Planet Earth (source). That’s bankruptcy on a global scale. And if Hemingway’s metaphor holds up, we can expect our bankruptcy to play out in a similar way: gradually, then suddenly.

By definition, involuntary degrowth is unplanned. It is what actually happens while we pretend we are doing something else, like maybe saving the planet with “green growth”.

Involuntary degrowth is, in Donald Rumsfeld’s famous phrase, an “unknown unknown”. As such, trying to predict its course beyond a few early warning signs is foolhardy. But we know what some of those warning signs are likely to be, even if we don’t know the exact order in which they are likely to appear. We also know that if some things happen, then other things are likely to happen as a result. This gives us some basis for anticipating how and when we are likely to experience involuntary degrowth, at first gradually and then suddenly.

Here are some developments that are more likely than not to accompany our descent into involuntary degrowth.

Prices go haywire

In our global economy, we really have only one real early indicator of trouble: prices. When the system is in relative equilibrium, consumption and production are roughly matched, so prices remain stable within a narrow range. But when either demand or supply get interrupted by “externalities” like wars, pandemics, or resource depletion, prices become highly volatile, economic planning becomes more difficult, economic actors become more cautious, and economic growth becomes more difficult (e.g., source). According to the International Monetary Fund, a leading promoter of economic growth and neoliberal capitalism, price volatility is already here, creating serious challenges for both rich and poor nations:

“The surge in food and energy prices during the past few years has fueled inflation and hurt growth. Prices of food and energy commodities increased steadily following the onset of the pandemic and reached historic highs after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. While international prices have since moderated, they have nonetheless contributed to upward pressure on domestic inflation. Moreover, high energy prices have increased input and transportation costs, weighing on economic activity and feeding into higher food prices through production linkages. The result has been a cost-of-living crisis, with the most vulnerable economies and people particularly hard-hit and with a marked increase in food insecurity.” (source, emphasis in original)

Central banks get more interventionist, bank failures become more common

When prices go haywire, central banks get involved. Their traditional approach, which they are not deviating from today, is to raise interest rates to dampen economic activity and bring inflation (prices) back down. As noted above, this is a demand-side solution that may be inappropriate if what we are facing is basically a supply-side problem, which is what it appears to be (source). One consequence of these central bank actions has been to expose weaknesses in other banks’ investment practices, resulting in bank failures like the recent demise of Silicon Valley Bank, the selling off of First Republic Bank, and the collapse and fire sale by the Swiss government of Credit Suisse to UBS. Overall, these tremors in the financial sector may be temporary, or they may be harbingers of further troubles ahead (source). As Nobel Prize winner Joseph Stiglitz has observed:

“… such increases in interest rates [i.e., “too far and too fast”] will not substantially lower inflation unless they induce a major contraction in the economy, which is a cure worse than the disease. An economic downturn like that is likely to have long-lasting adverse effects, and the most marginalized in society will bear the brunt. Volatile energy and food prices are largely internationally driven and not under the control of the Federal Reserve. The recent aggressive hikes have not remedied these price increases and are unlikely to do so in the future.” (p. 5)

This is sounding more like a contributor to involuntary degrowth than a solution.

Recession, then depression

If inflation-fighting fails, recession is the likely next step in our descent into involuntary degrowth. From a purely environmental point of view, a recession has one redeeming feature: it slows down economic activity, which slows down energy demand, which decreases the rate at which we release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, which decreases the rate at which we cook the planet (source). But this benefit is achieved at a significant economic and social cost, as Stiglitz and others have warned.

If the global economy slides into a recession, what might keep it from sliding into an even deeper depression? We know how recessions normally end: interest rates go back down, businesses start hiring again, wages and consumer spending rebound, businesses record higher earnings, the stock market and GDP tick up. Everybody’s happy again. But what if business growth is thwarted not by inadequate demand, but by inadequate supply? That’s what resource depletion is all about, a failure of supply. In an earlier post, I documented how many basic commodities are already showing signs of depletion:

“On the supply side, we are beginning to experience shortages and disruptions in the availability of many critical materials and commodities: sand, cement, copper, other “critical” minerals like lithium and cobalt, along with microprocessors themselves. In addition, climate change, COVID, and the war in Ukraine are having a significant effect on global food supplies, producing shortages in wheat and other grains. Even coffee beans.”

Should any of these shortages fail to be alleviated by discovering new supplies or inventing new substitutes, we may not have the ability to climb out of the next recession before it transitions into a longer-term, more severe depression (source). This danger is likely to be exacerbated by the biggest resource depletion issue of all: the decline and eventual disappearance of fossil fuels as our civilization’s primary energy source.

Also, note that when supply disappears, consumption automatically declines, regardless of the level of demand the consuming public might entertain. Americans may not stop eating meat when asked to do so, but they will definitely stop eating meat when meat is no longer available at their local markets, or priced so high as to be unaffordable. That’s how involuntary deconsumption works. And there is one thing we can say about it with certainty: it’s going to make people very, very angry.

Escalating extreme weather events disrupt economic flows and destroy resource stocks

All of the developments described so far are functions of resource depletion. They are all current or potential byproducts of the declining supply, quality, and cost of fossil fuels and other nonrenewable resources. They would be problems today even if fossil fuels did not cause global warming. But they do. And global warming is not to be ignored.

Rising temperatures are already significantly disrupting the global economy. A recent article in the New York Times observes:

“Of all of climate change’s threats to supply chains, sea level rise lurks as potentially the biggest. But even now, years before sea level rise begins inundating ports and other coastal infrastructure, supply chain disruptions caused by hurricanes, floods, wildfires, and other forms of increasingly extreme weather are jolting the global economy. A sampling of these disruptions from just last year suggests the variety and magnitude of climate change’s threats:”

I won’t repeat the sampling of disruptions here. Suffice it to say that 2022 was a horrific year for climate catastrophes (e.g., source, source). But it’s just the beginning (source), and it’s producing feedback effects that are magnifying the economic impacts of resource depletion. The Times article continues:

“As the ripple effects of what are likely to be ever-increasing and intensifying climate-related disruptions spread through the global economy, price increases and shortages of all kinds of goods — from agricultural commodities to cutting-edge electronics — are probable consequences.”

Extreme weather events can be expected to exacerbate and accelerate price volatility, central bank interventions, and ongoing pressures on GDP. This will seriously inhibit the flow of goods around the world.

But the effects of climate change on the world’s economy will be felt first and most devastatingly in the Global South, where heatwaves, floods, droughts, coral reef die-offs, sea level rise, disease, and inadequate infrastructure in large parts of Africa, Asia, and South America are likely to put the lives of billions of people at risk, rendering those regions at first unproductive and eventually, depending on how hot it gets, uninhabitable (source, source).

If citizens of the Global North think these effects can be confined to the Global South, they are sadly mistaken. A recent study quantified the extent to which consumption in the North is dependent on the resources, land, and labor of the South. According to this analysis, the North’s dependence on cheap products and labor from the Global South adds up to an appropriation of approximately 12 billion tons of “free” raw material equivalents every year, making up 43% of the North’s total annual material consumption. In other words, nearly half of the North’s annual material consumption is net appropriated from the South.

Should this source of cheap products and labor dry up (literally), the effects on consumption in the North will be devastating, far greater than any shortages experienced in the past. As the impacts of extreme weather in the South accumulate, consumers in the North will begin to see a wide range of products disappearing from their store shelves. From fresh foods to household goods to building materials to automobiles to spare parts, things will become more scarce and more expensive. In response, governments will need to impose interventions to discourage hoarding, price-gouging, or other forms of unfair allocation of these now-scarce consumables. This brings us to another likely effect of involuntary degrowth: rationing.

Rationing

When prices fail to balance supply and demand, the next step is rationing.

As energy analyst Richard Heinberg has observed, rationing will be necessary to make sure we prioritize our dwindling fossil fuel reserves so they are directed at building the energy-transition infrastructure we will require when fossil fuels are gone, a task which we currently cannot accomplish without rationing our remaining oil, gas, and coal supplies.

“The best answer is a managed reduction in fossil fuel extraction accompanied by a rationing system that preferentially directs declining fossil fuel supplies toward energy transition projects while distributing remaining fuel supplies to industry and households for only the most essential purposes. Programs would also be needed to offset the impacts of scarce energy on lower income households and countries.

“Policymakers may find this unthinkable, because they have built their careers on the assumption that the economy must always grow, and that people must always be promised the opportunity to consume more. Yet until public discussion turns in the direction of managed energy descent and rationing, nothing will happen to avert climate hell.”

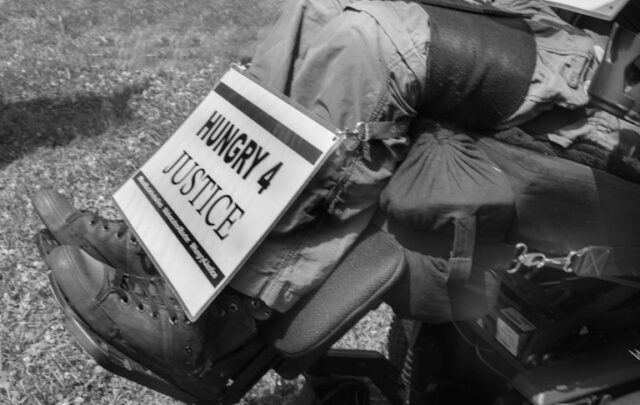

Rationing is likely to be a necessary stop along our way to involuntary degrowth (source). Because it will remain toxic to political leaders (for reasons discussed in Part 1 of this series), it is unlikely to be adopted in a careful and controlled manner that citizens will understand and embrace. Rather, it will probably be introduced only as a last result, after considerable deconsumption has already been felt, and in the face of much public opposition. Given past opportunities to sacrifice for the common good,¹ citizens of the Global North have not shown much inclination to engage in altruistic resource sharing. A more likely response is an increase in civil unrest and political instability.

Civil unrest, political instability

My working hypothesis is that people in the Global North are not going to give up their advantageous position in the global hierarchy willingly.

Rationing in the Global North may become one trigger of civil unrest, but it is hardly the only one. As the century unfolds, world populations will face multiple sources of stress and anxiety, in both the North and the South. We know these stressors will only increase in frequency and severity as we continue to pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere over the next decades. In a world of growing scarcities, extreme weather events, increasing environmental destruction, and unprepared governments (in both the North and South), we can expect a spike in social instability and political conflict, both within and between nations.

Nations drift toward protectionism, repression, and isolationism, causing climate mitigation efforts to turn inward

As the climate heats up, as agriculture and manufacturing collapse in the Global South, and as governments in the Global North become more and more preoccupied with climate damage and economic shocks within their own borders, nations may become less committed to coordinated global action and more inclined to “go it alone” by abandoning mitigation solutions (ways to avoid the worst effects of climate change) in favor of adaptation solutions (ways to cope with the worst effects of climate change). This drift toward adaptation over mitigation is likely to be a luxury only the most wealthy nations can afford.

As nations turn inward, as civil unrest grows, and as climate disasters multiply, politically-acceptable “solutions” to climate breakdown and resource depletion are likely to become more interventionist externally and more repressive internally. Externally, we are more likely to see the powerful take what their populations demand from the less powerful, whether “strategic” minerals, fresh water, or arable land. Internally, it will be hard for democracies to survive, as deconsumption and escalating natural disasters cause populations to lose trust and confidence in their governments, creating conditions ripe for the rise of repressive authoritarian regimes.

Large political units (nation-states) become unmanageable and ungovernable, triggering involuntary “de-complexification” of no-longer-sustainable institutions

The problem with authoritarian regimes is that they have little interest in fighting climate change or adapting to resource depletion (source). Indeed, the idea of a pro-climate authoritarian regime may be an oxymoron. Authoritarian regimes are not designed to solve problems, they are designed to pillage a nation’s assets and funnel as much national wealth as possible into the coffers of the elites who hold power (source). Whether we’re talking about Trump in America, Bolsonaro in Brazil, or Orbán in Hungary, all these authoritarians are climate change deniers and enthusiastic supporters of continued exploitation of fossil fuels.²

Authoritarians take care of authoritarians, not the planet.

As nation-states begin to lose their capacity to control their own citizens, we reach the point at which “gradual” bankruptcy turns into “sudden” bankruptcy (source). Energy is not only the glue that holds our economies together, it is also the glue that holds our societies together (source, source). Our 200-year fossil fuel binge has allowed us to build a much more complex civilization than we ever could have created with less dense and plentiful energy sources (source). Now, as that era of energy abundance is coming to an end, that complexity itself is unlikely to be sustainable.

When complex systems can no longer be supported by available energy sources, they collapse (source). They descend to a lower level of complexity. This doesn’t mean they sink in barbarism, Mad Max-style. But it also doesn’t mean they descend without conflict or suffering. Rather, it means large, complex systems decompose into smaller units that can meet human needs with less energy than was previously available. Their geographic reach shrinks, they become more localized, and they settle into a level of complexity that is sustainable given the energy sources now at their disposal (source).

In this way, large nation-states may devolve rather quickly into simpler, smaller, largely autonomous political units that provide their own legal and enforcement institutions. The larger state, in Marx’s evocative term, may simply “wither away”.³ This is how a world of large, complex nation-states can rather suddenly turn into a world of small, localized communities and regions, each essentially responsible for its own survival. Perhaps they can learn from our mistakes and build a more sustainable world that lives within planetary boundaries.

In Conclusion

Human beings do not change easily. We tend to get “stuck” in our mental models. This is where we are today:

Our leaders are wedded to a mental model of perpetual growth and capitalist accumulation that no longer fits the planetary challenges we face. They are trying to solve the global problems of climate change, overshoot, and resource depletion using the same instruments that caused the problems to appear in the first place.

Clearly, decades of increasingly strident warnings from the scientific community have not changed our trajectory. Persuasion has not worked. Exhortations to “heed our better angels” have not worked. Painting visions of future hellscapes has not worked.

I believe we will only abandon our mental model of economic growth and capitalist accumulation involuntarily, kicking and screaming, deflecting, denying, and resisting. Powerful political and economic forces will continue to support the model and defend it until long after its expiration date. This failure to embrace inevitable change will add incalculable damage and suffering to our transition out of the Age of Oil. It may, indeed, end us before we have a chance to come to terms with our situation and begin rebuilding our civilization along more sustainable lines. Or it may only wound us, in which case we may be given a second chance in a post-carbon world that is smaller, simpler, more local, and more sustainable.

We are indeed ants on a log, caught in a current we cannot control, some of us seeing the waterfall ahead, others still refusing to acknowledge it’s there. So we argue and debate, exhort, resist and deny. All the while, we fritter away our limited time to act. Meanwhile, we drift closer and closer to the waterfall.

We will go over the waterfall. I don’t see how we can avoid it. In anticipating what comes next, perhaps we can draw some strength from a different Hemingway quote:

“The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places.” — Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms, p. 267.

Notes

- To get a preview of how at least some Americans are likely to respond to rationing and deconsumption, we only need to consider the rejection of masks and vaccines during COVID, an anti-altruistic stance that Republicans embraced enthusiastically, at a cost of 76% more deaths among Republicans than Democrats in two GOP-led states (source, see also source). Another example of this unwillingness to consider the needs of others is Americans’ gun fetish, which allows them to prioritize their “freedom” to own military-grade weapons, overriding the obvious fact that those weapons are regularly used to slaughter their own children (source). These are wildly irrational, even insane, examples of an infantile attachment to selfish, self-centered values. They do not bode well for an orderly, reasonable, well-managed, voluntary transition to the post-carbon future that awaits us all.

- For fans of authoritarian regimes, it is worth noting that only through democratic elections were we able to remove Trump and Bolsonaro from power. Orbán is still there. When elections are eliminated or thoroughly corrupted, authoritarians are much, much harder to remove. Maybe democratic accountability isn’t such a bad idea after all.

- Although hardly in the way Marx and his collaborator Engels thought it would.