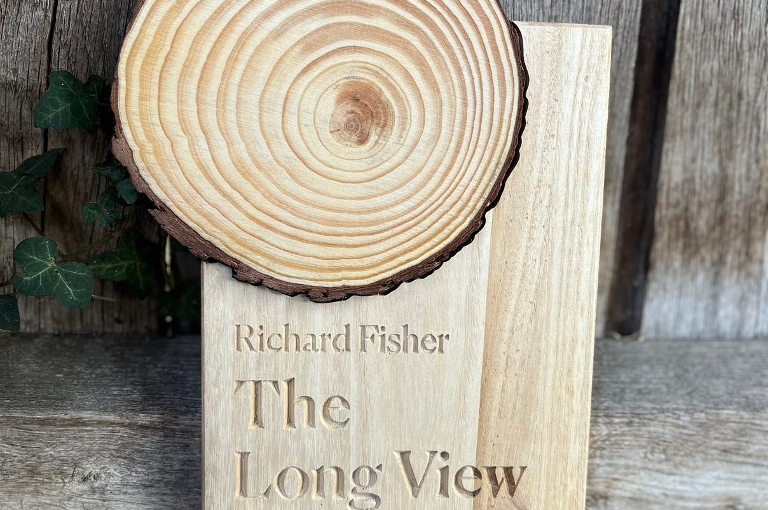

Richard Fisher’s book The Long View: A Field Guide was published this week—my copy has just arrived—but to mark the occasion Richard published on his blog an interesting lexicon of phrases about what he calls “long-terminology”. Well, you can see what he just did there.

This isn’t just about neologisms for their own sake. The argument for why we need such a lexicon is pretty straightforward:

After all, if we lack the language to talk about the long-term, then we’re less likely to think about it.

(Wood engraving by Luke Blades and Jenna Peters. Photo via Richard Fisher. Story here)

‘Time-blinkered’

The four examples in the post are ‘time-blinkered’, ‘temporal stresses’, ‘temporal habits’, and ‘long-minded’. The first and last of these seem most interesting to me in terms of their effects, one negative, one positive.

‘Time-blinkered’ refers to

unwitting, invisible short-termism: a lack of awareness of long-term consequences and responsibilities that’s so hidden from view that it barely gets mentioned… It is a trait that has become so embedded in modern life that people are not even aware it’s there. Identifying the causes is, I believe, crucial if we want to discover a longer view.

Reading this I was struck by a couple of connections. The first was to the idea of ‘slow violence’, Rob Nixon’s idea which speaks to environmental damage or social damage done by the slow accretion of change. (Someone seems to have uploaded his whole book online).

The second was Peter Drucker’s idea of ‘the future that has already happened’—changes that are already in motion that will have effects sooner or later. (From memory he uses the example of the doubling of the income of black American households between 1946 and 1961, which then shaped political, cultural, and economic change).1

‘Long-minded’

‘Long-minded’ is the antithesis of this.

Long-mindedness, to me, means stepping back and seeing where we sit on time’s long arc: learning from the deep lessons of history, as well as nurturing and maintaining an awareness of the impacts of actions on the future.

It also complements present-mindedness: which means to consciously and mindfully focus on the moment when it matters, whether that is to tackle urgent crises or simply enjoy life’s pleasures. Unlike time-blinkered thinking, this is a positive form of short-termism. After all, if we thought long-term all the time, we’d miss out on what matters now.

As he says in the piece, he used to use ‘long-termist’ to describe what he now calls ‘long-mindedness’. But unfortunately the world ‘long-termist’ has been captured by the ‘effective altruists’, a group with a very particular ideological view of how we should approach our orientation to the future.

(Even the name is loaded, of course, distinguishing the smart and well-considered “effective” altruists from all of us other poor saps who are completely “ineffective” in our altruism. It’s enough to make you stop giving at all.)

Effective altruists

As it happens, Fisher also has a long article in Vox taking the effective altruists to task for one of the fundamental tenets of their worldview: that we can’t help future generations if we’re busy helping present generations. Not to gloss his argument, but he’s not impressed.

EA longtermists propose that positively influencing the long-term future is a key moral priority of our time — and in its strongest form , it becomes the key moral priority. This apparently zero-sum framing — present needs versus future needs — may go some way to explain why longtermism has attracted so much controversy in recent months… In the eyes of critics, longtermist philosophy would seem to prioritize the aggregate well-being of 100 trillion-plus hypothetical people in the future over the actual living, breathing 8 billion people alive today.

It’s a rich article, and it brings to life some of the range of ideas that I’m expecting to see in the book when it does arrive. One of the most interesting aspects to me is that he’s taken time to explore futures thinking—long mindedness, if you like, in a range of cultures. It turns out that there’s not an either/or tradeoff between the future and the present:

Encountering all these different perspectives has shown me that taking the long view can and should be plural and democratic. And crucially, they demonstrate that extending one’s circle of concern to tomorrow’s generations needn’t mean prioritizing the future above all. If anything, I’ve discovered that taking a longer view can often lend greater meaning to life in the present: offering perspective and hope amid crisis and difficulty, and a source of energy, autonomy, and guidance when it’s needed.

Fisher has been releasing a whole lexicon of words on time into the wilds on Twitter, one a day, at the hashtag #longterminology. Each has come with a few words about their origin. Over the last few days, these have included ‘deep time’, ‘industrial time’, ‘environmental time’, ‘timescapes’ and ‘future fossils’.

Here’s the tweet for the last of these:

Today’s #longterminology is Future Fossils: These are the industrial, chemical and geological legacies that we will leave behind for future generations, a term coined by the University of Edinburgh’s David Farrier (@David_Farrier). pic.twitter.com/ahiiS8ylyM

— Richard Fisher (@rifish) March 24, 2023

[1] Of course, even after this had happened, average household incomes for black American families were still some way short of those of white American families.

——-

A version of this article was also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.