This article first appeared on ARC2020.eu. (Part 2 is posted separately on ARC2020 here.) ARC2020 is a platform for agri-food and rural actors working towards better food, farming, and rural policies for Europe.

Rural Europe Takes Action – No more business as usual”, the book published by ARC2020 and Form Synergies in June last year, ended with a mysterious unwritten regulation, the Common Agricultural Policy of the future. Only it is not. It is much broader than that. We called it the European Rural and Agricultural (and Food) Policy (ERAP). So, what is it about and why is it important to talk about it now? Let’s dive into it.

An underachieving CAP

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is undoubtedly Europe’s flagship legislation. It has been around for 60 years, eats 31% of the total EU budget and no one ever seems to be content with it. But why is that?

The aims of the CAP, as stated on the European Commission (EC) website, are to:

- Improve agricultural productivity;

- Ensure decent incomes for farmers;

- Help tackle climate change and the sustainable management of natural resources;

- Maintain rural areas, landscapes and keep the rural economy alive.

But how did the CAP perform on these?

Improved agricultural productivity

The only exception to the overall underachievement of the CAP might be agricultural productivity, which has been growing continuously.

But since 2005, the trend has slowed rapidly. Total Factor Productivity (TFP), an indicator representing the ratio of agricultural output (production) to their input (such as land, labour and capital), shows a sharp drop in growth for the oldest Member States (EU-15), from 1.3% (1995-2005) to 0.6% (2005-2015). Germany even recorded negative TFP growth in recent years.

This remaining growth is mostly explained by a shortening in workforce, as the number of farmers continues to decline in the EU. Labour productivity has increased, maintaining an overall positive TFP.

So, for now, agricultural productivity is still slowly increasing. But this trend can only be maintained as long as fewer and fewer farmers, through the extensive use of expensive machinery, chemical fertilizers and pesticides, continue to farm more land. But at what cost for our climate and biodiversity?

Ensure decent incomes for farmers

Through the 1992 MacSharry CAP reform, the goal was to take a big step towards the support of farm incomes in that product support was replaced by producer support (area-based subsidies). But 30 years later, according to the EC numbers, the average farmer income is still around 40% lower compared to non-agricultural income.

And it is hard to believe that the current CAP will change anything about it, as 80% of the budget goes to the 20% largest farms.

Help tackle climate change and the sustainable management of natural resources

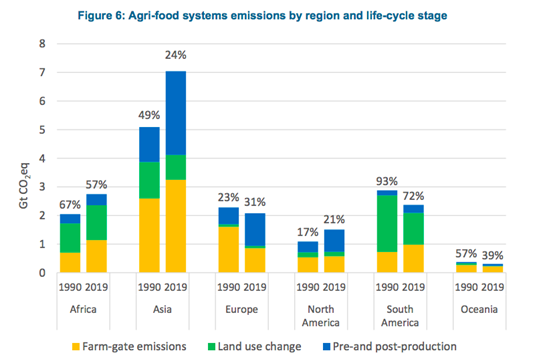

Reducing GHG emissions in the agriculture sector has been a slow process. According to the FAO, while GHG emissions of agri-food systems represented 23% of total EU emissions in 1990, it now represents 31%. Since 2005, the reduction rate has been mostly stagnant.

According to the European Environment Agency, and based on EU Member States current policies, this trend is projected to continue through 2040, with only a 1.5 % decrease expected between 2020 and 2040.

Interestingly, while on-farm emissions were the main driver of total agri-food emissions in the 1990’s EU, it is now pre- and post-production emissions that take the first spot. This shows that an integrated approach of agri-food systems is needed to tackle emissions.

Figure 1: Agri-food systems emissions by regions; source: FAO 2021; The percentages indicate the share of agri-food systems in the total emissions of the region

Natural resources are in no better shape. Pesticide use in the EU did not decrease over the past 10 years, despite their toxic effect on biodiversity. Soil erosion is about two times higher than soil formation in agricultural lands of the EU. And to palliate this loss in fertility, chemical fertiliser use increased in the past 10 years (+6.9% for nitrogen ; +21.9% for phosphorus).

Maintain rural areas, landscapes and keep the rural economy alive

Since the 1999 reform which introduced the two pillar structure, the CAP has aimed to promote the development of rural areas. But so far, rural development measures have primarily targeted agriculture (e.g. through farm investments, farmer training, environmental protection in agricultural ecosystems).

To analyse the impact of the CAP on rural development, we have to look at economic, demographic and social evolutions. On those:

- The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita in rural areas is on average 70% of the EU average.

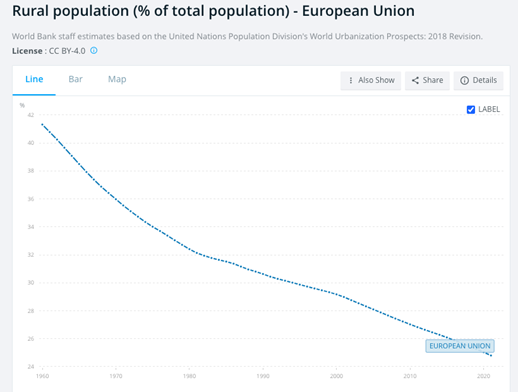

- Rural exodus has not eased in 60 years (see figure 2).

- The number of farms dropped by 37% between 2005 and 2020. The EU lost 2 million farms (one quarter) across the Member States between 2005 and 2016, about 85% of which were farms under 5 ha.

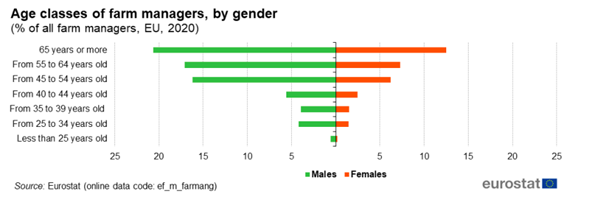

- Young farmers (under 35 years old) represented only 7,3% of farm managers in 2005 and 6,5% in 2020.

- Only 29% of farms in the EU are managed by women. And only 4.2% of those women are under 35 years old while 42% are older than 65.

Figure 2: Evolution of rural demographic in the EU (source: World Bank)

Figure 3: Age classes of farm managers, by gender (source: European Commission)

Those issues are not only numbers. One of the greatest challenges in rural areas right now, and especially for farmers, is loneliness. A few years back, as part of my master’s thesis, I visited dairy farmers in Wallonia to discuss their social contexts. Loneliness and isolation were often cited as a great burden that, mixed with financial issues would lead to suicide. Here is what one of them told me.

“In the past I worked outside the farm and when I stopped, from one day to the next I was cut off from social life. (…) I suffered from it. I missed my social life, I’m not afraid to say it.”

The Commission and the European Parliament must team up and acknowledge the lack of suitable EU response to these rural issues: fewer local education or job opportunities/choices, difficulties in accessing public services or transport services, inadequate internet or health coverage, or a lack of cultural venues/leisure activities[1].

A new European Rural and Agricultural Policy (ERAP)

The impact of the CAP is not only negative. And all the problems in agriculture and rural areas are not to be blamed on it. In the last decades incremental changes in the policy have given opportunities for farmers to steer their practices in the right direction (e.g. budgets for greening measures, organic farming, young farmers, environmental and climate actions, eco-schemes (their impact still needs to be assessed)).

The CAP can be a very useful tool. But for now, it mainly maintains the intensive agri-food model. It leaves some room for alternative types of farming but will never make them the norm without a complete makeover.

For those reasons, many think it is time for the CAP to retire. Or at least, the CAP as we know it. The EU commission is planning to propose the first key points of a post-2027 proposal as early as 2023. And with the EU elections coming in 2024, it seems like now is the right time to start seriously reflecting on it.

Let’s put ARC2020’s unwritten regulation (that you can find in our book “Rural Europe Takes Action”) in the spotlight. The unwritten regulation is a draft text for an integrated rural, agricultural and food policy to be adopted by EU institutions in 2027 at the latest. It is not a finished product but a first proposal to be built upon.

This unwritten regulation, for the sake of argument and an eye-catching result, was written in the legislative style. Here, we want to take out the main learning points, plain and simple.

An integrated rural approach

The policy focus shifts from mainly direct income support for farmers to the development of rural infrastructure. The goal is to empower all rural actors and ensure a fair distribution of added value on the local and territorial level, which would eventually decrease farmer’s dependency on income support. Those infrastructures should allow our agri-food systems to highly reduce their dependence on mineral oil as well as feed and food imports from global markets.

This overarching policy will thus empower rural actors to democratically build resilient food systems that can answer the challenges of our time: climate change, biodiversity loss, depletion of soils and water reserves.

Public income support will still be available for farmers but will be distributed based on agro-ecological-social criteria. As far as agricultural production and processing is concerned, what is currently the common rule will become the exception. And the organic exception will become the rule.

Merging the funds

The ERAP proposes to redesign the funding structure that delivers the CAP. The CAP has been historically financed by the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD).

As I explained in the previous chapter, the addition of a second pillar, financing rural development through the EAFRD and co-financed by Member States, was supposed to ensure sustainable management of natural resources and climate action and enhance territorial development of rural economies and communities. But the budget distribution has never reflected those objectives.

In the current reform, EAFRD budget has also shrunk. A 19% decrease in Pillar II appropriations in the 2021-2027 programming was recorded compared to 2014-2020.

To alleviate these budgetary constraints, both funds will be merged under one European Rural and Agricultural Fund (ERAF). A new fund for a new policy. Moreover, the ERAF will be integrated in the European Cohesion Policy (which is based on Structural Funds such as the European Regional Development Fund, and the European Social Fund). The European Cohesion Policy aims to achieve the objectives of economic and social development of regions and territories, territorial competitiveness and the reduction of growth and living condition gaps between regions and territories. It does not (yet) highlight rural areas as priorities but the inclusion of the ERAF in the fund package should solve this issue. This could create a more integrated Cohesion Policy and tune it to current challenges for the EU.

A bottom-up delivery model

To decide who gets what, the ERAP is opting for collaborative intelligence. National and regional programme authorities will have the choice between the CLLD and LEADER approach to bring local actors together and form governing bodies that will decide how to improve their area.

A minimum of 5% of the ERAF budget must be allocated to the CLLD/LEADER for this purpose.

A revised subsidy system

The ERAP is (for now) made up of 4 articles. Article 1 lays down the general rules of the policy and articles 2, 3 and 4 address the distribution of subsidies.

Basically, this new policy will tackle its objectives through 3 different approaches.

- Rural cooperation and infrastructures

- Development of sustainable short supply chains and better distribution of added value

- Farm support

In all of those approaches, capping is introduced with ranges from €100,000 to €200,000 depending on the subsidy type and the structure that is applying.

1. Rural cooperation and infrastructures

While in the current CAP, most of the Member States are relying on LEADER interventions to address the socio-economic development of rural areas, the scope of available interventions under ERAP will strongly increase. Budget will be available for three types of projects.

First, funding will be provided for projects that intend to develop rural infrastructure and services, such as eco-mobility systems, IT connectivity, preservation of rural heritage, and cultural activities. Specific investments to improve generational renewal in farming but also disaster prevention and environment-climate friendly provision for farms, SME, public and civil society organisations will be available as well. All projects that can improve raw material use and circularity of the economy will also be financed.

Second, funding will focus on projects that will improve networking and knowledge sharing capabilities. These projects will be financed either through cost reimbursement, for example for the qualification of employees or through the investment in learning projects (schools, conferences…).

Third, the ERAP will support cooperation projects, such as producer groups, business cooperation, civil society initiatives, co-working spaces and more. EIP operational groups will be financed to support economic and social innovation projects, as well as quality schemes promotion. Finally, the budget for LEADER will increase to a minimum of 5% of the whole ERAP budget.

2. Development of sustainable short supply chains and better distribution of added value

The EARP will focus on the development of sustainable value chains. The goal is to empower local actors of the rural economy that will reinforce local implementation of the food production processes and the rural economy as a whole. Eventually, localised short supply chains will organically redistribute the added value in a more equitable way along the chain, financing a diversity of rural actors and projects.

Support will be allocated firstly to the development of agricultural, food and forestry value chains. Concerned projects range from seed, feed, leguminous crops, renewable raw materials production to water saving, waste reduction or culinary partnership projects.

Support will also be reserved for economic actors from secondary and tertiary sectors, such as craftsmanship, gastronomy and tourism.

3. Farm Support

Public income support will still be available for farmers. The current structure of the subsidy system remains with decoupled payments being distributed to farmers as long as they comply with conditionality rules. The payments are still area based but their framing is completely redesigned.

- The compliance rules or conditionalities are based on world-wide organic standards for production and processing of plants for food, non-food crops, wood, livestock and aquaculture. It will regulate the increasing use of agroecological practices and ban of active chemical substances used in the EU or exported.

- The general objective is that, by 2030, all ERAP support is tied to organic standards.

- All direct payments are to be indexed with a farm labour factor (based on an algorithm still to be defined).

- Direct payments are all capped at €100,000, with high redistributive obligations (triple payments on first 5ha and double on the first 20ha) and degressive

- Young farmers will see their subsidies doubled for the first five years of activity.

- Additional payments are planned for farms with geographical and environmental constraints.

- Complementary support is provided to farmers for the implementation of practices that provide additional environmental and climate services.

Conclusion

The goal of writing this proposal was not to have a finished product but to start a debate. Everyone who would like to add on it and discuss specificities should do so. And everyone will have their own sensibilities for specifics of rural and agricultural transition. What about social conditionality? What about health care and doctor shortage in rural areas? What about access to land? What about meat consumption? What about market regulation? All those questions should provide for many additional articles to this unwritten regulation. Let’s write it together.

We invite unions, NGOs, public services and citizens to build upon this proposal. The time is now.

In the meantime, I would like to already provide my answer to the question that will arise, and it might be on your lips already. How much will it cost (for it to succeed)?

Short answer, we don’t know (yet). Anyone wishing to make a calculation is most welcome. What we believe is that, even with a similar budget to the current reform, results would already be much improved. But why not increase it?

Some might not care enough about rural areas, but everybody cares about food. And the fact is that we currently underspend on food. We’ve never spent less (2022 inflation aside). For some, this is the reflection of great progress. But is it really? We now live in a world where soil erosion, climate change and biodiversity loss are putting long-term food security at risk. Moreover, the food we produce is increasingly less nutritious. The industrial model on which large agglomerations are being fed is based on over-processed food products, full of fat and sugar to please our brains. Most of the world’s population now lives in countries where overweight and obesity kill more people than underweight. Worldwide obesity has tripled since 1975 and around 2 billion people are now overweight. Where is the progress in that? And that is the result of a system. As we say in French, ce n’est pas par l’opération du saint esprit (it wasn’t by some miracle).

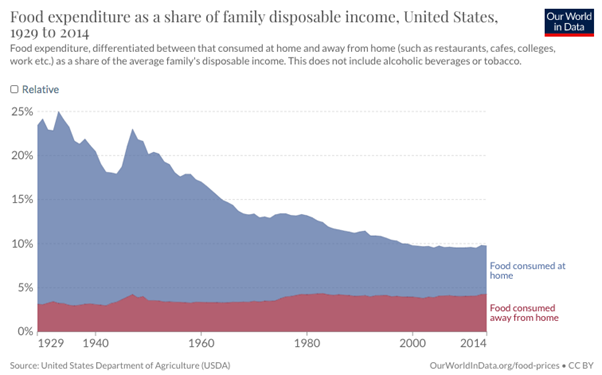

Below is a graph representing the evolution of food expenditure as a share of household’s disposable income (net of taxes). It shows the trend for the US, which has been recording those data much longer than the EU. But results are close. In the EU, in 2019, food expenditure represented on average 13% of household spending.

Figure 4: Food expenditure as a share of family disposable income, US (source: our world in data)

Moreover, the CAP budget represents only about 0.4% of the EU GDP. It has been higher in the past but never surpassed 0.7%. To allocate such a small part of our GDP might not be enough for a complete revitalisation of rural areas and transitions of agri-food system to agroecology. That is also why the proposal we are making is one that intends to redistribute added value along the production chains.

And thus, we might have to accept to pay a little bit more for our food, through prices or taxes. And with this debate will come a time, the sooner the better, for a new social contract in the EU, the infamous “who pays what”. But that is another chapter for this story.

[1] https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/60569

This article is produced in cooperation with the

This article is produced in cooperation with the

Heinrich Böll Stiftung European Union.

Photos author supplied.