A story about the possibility of creating genetically engineered radioactivity-resistant soldiers last week made it seem that life was imitating art. I am currently rewatching “The Expanse,” a popular science fiction television series based on a book series of the same name. I recommended it in 2018 as an entertaining and disturbing tale illustrating the concept of systemic ruin, a possibility that our civilization faces on a number of fronts.

In “The Expanse,” far in the future as war between Earth and Mars nears, evil men (and women) create an army of soldiers who live on radioactivity and who require no spacesuits. These evil scientists do this by transforming human captives using something dubbed the “proto-molecule.” These so-called “hybrid soldiers” are remorseless killing machines and can also infect humans with the “proto-molecule” by merely spreading it around. The general advice is not to get near these soldiers or touch the blue goo that they seem to be able to generate.

Back on Earth in the 21st century—beyond the morally repugnant idea of genetically engineering babies to later become radioactivity-resistant soldiers—we have bioengineers who seem to forget the first rule of ecology: You can never do merely one thing.

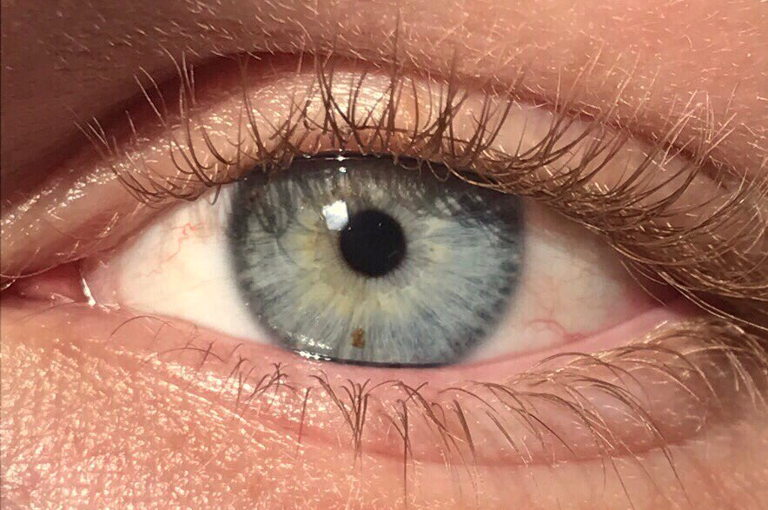

First, there is the problem of what a trait is. Eye color has a clear genetic marker. Shyness does not. Words are very slippery and only point to realities we are trying to describe. They are not realities in and of themselves. And, the meaning of words such as “shyness” is not always clear and cannot be precise and measurable the way eye color is. And, of course, shyness is almost certainly shaped by the social environment in ways that eye color cannot be.

Second, there is more than one model of how genes affect traits. When it comes to humans, the idea that one gene was responsible for one trait is in most cases wrong. Instead, human genes are multitaskers affecting many traits. Going further, the omnigenic model suggests that all complex traits are governed by all genes working in concert. That means changing one gene or set of genes is likely to change a lot of other things in unpredictable ways.

Third, changing the genetic make-up of a significant segment of the population—and soldiers are a significant part of nearly every society—will transmit those changes to their children. If these changes make humans less resilient, the changes could threaten the viability of the entire human race as they are spread over time.

Fourth, we imagine that we know what a “desirable” trait is. But in many cases what we think of as desirable is merely a cultural convention. It has nothing to do with what would make humans more robust and healthy within their environment. A naturally trim physique might be thought to be aesthetically pleasing to others. But, in a future time of scarcity, the natural human ability to store excess calories as fat may mean the difference between surviving and dying.

I am doubtful that the researchers mentioned above will get very far with the creation of their own genetically engineered soldiers for technical reasons as well as moral ones. But the ideas such efforts propagate only push us further down the road to ecological devastation as they legitimate one of the most destructive ideas in the modern era: That we CAN do just one thing and that if that doesn’t work out, we can always mitigate the consequences with even more technical fixes—which, of course, create their own cascade of problems…and so on.

Image: By Lucashawranke – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58184874