Ed. note: I have combined 2 of Gunnar’s latest posts into one as I think they complement each other very well.

The agriculture treadmill eliminates both farmers and profit

Despite enormous increase in productivity, farming is in general not profitable and the strategy of international competitiveness that dominates the farm sector in many countries is doomed to lead to ever decreasing profits and ever decreasing number of farmers.

This article draws on the four number-crunching articles posted here the last month and adds some analysis, particularly economic.

The development of productivity in farming is mind-boggling. 200 years ago the time spent to harvest and thresh one ton of grain was around 30 workdays. The job is now done in five minutes with a modern combine harvester – and John Deere X9 actually can harvest up to 100 ton in one hour if conditions are optimal. Not only has work productivity increased a lot, the yield per area unit has increased as well. As demonstrated here, world agriculture output of crops, measured in tons, has increased with 268% since 1961. The population increased with 151%, i.e. the production per person increased with 43%. This has been accomplished with an increase in cropping area with “just” 20 percent. The work force increased until 2003 when it amounted to 1.06 billion people, but after that it dropped considerably and is now around 0.84 billion.

In high income countries, the agriculture work force dropped from 66 million persons 1961 to just 16 million 2020, i.e. three out of four farm jobs have disappeared, most of them being farmers. Meanwhile the output doubled, which means that value per person employed increased 700 percent. Still farming is not a very profitable venture in most countries. There are always some exceptions to this rule either as a result of a specific policy environment or as a result of some individual farmer being superior managers or business people, or just happen to be in a sweet spot at the right time.

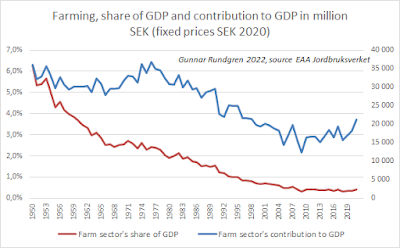

Looking a bit closer on Sweden, my home country, we can see that the share of the GDP originating in farming has shrunk from above 6% to just 0.4% in seventy years and that the total contribution to the GDP (i.e. value added in production) has dropped considerably. Value has dropped despite the fact that total output in volume has increased, roughly by 10%.

Looking at the situation from a farm business perspective, the overall picture shows a remarkable shift around 1990. Until then, Sweden pursued a policy of self-sufficiency through a combination of tariffs and support. That was abolished in the end of the 1980s and was followed by EU membership in 1995. That increased competition a lot and prices dropped. The situation has improved a bit but profitability is still very low as prices of inputs used have also increased. The net farm income corresponds more or less to the subsidies through the EU Common Agriculture Policy.

The development in Sweden and other high-income countries confirms the accuracy of the agricultural treadmill as observed by the American agricultural economist, Willard W. Cochrane.

The agricultural treadmill begins to spin when new technology is developed and implemented by pioneering farmers. These early adopters gain an economic advantage from the new technology, because they can produce at lower costs at unchanged selling prices. As more and more farmers use the new technology, production increases and prices fall, however. The economic advantage gained by early adopters disappears as it is offset by falling prices. This is then repeated again, again and again. The early adopters may be profitable for a while, but they have to continually innovate to remain that. The laggards park their tractors for good and the big majority of farms live on rust and rot (as we say in Swedish meaning they can’t afford to re-invest in their farms, just making ends meet a year at the time).

Ironically it is not even countered by subsidies as they lead to lower prices or higher land prices or any combination of them. For the farm sector as a whole there is actually little point in all that innovation and increase of productivity as it is the buyers and consumers that will reap the benefits and not the farmers as a collective.

Food: away from the market into the civil sphere

In my last article I explained how the agriculture treadmill works. As long as there is an underlying overproduction of agriculture commodities, agriculture will never be profitable in the normal meaning of the word. One agriculture economist in Sweden claimed that, because of this, prices of agriculture commodities are mainly determined by how cheaply farmers are ready to work. This is also reflected in the mostly bad conditions for farm workers.

There are, of course, individual examples of farmers who can make a profit. As the treadmill theory points out, pioneers in adoption of new technology can often benefit for a while, but they will have to continue to be in the forefront year after year. There are also risks with being the earliest adopter, as technologies might not yet be perfected or even dysfunctional. More often it is better to stand in the second line.

Another strategy is to avoid “commodity hell” A version of this is to go for a special niche in the market. It can be a new crop or a new production concept. Many years ago our farm was the first to cultivate daikon radishes on a semi commercial scale in Sweden. We grew thousand square meters, got a bumper crop and very good prices when we shipped them to the market in Stockholm. Next year we sowed three thousand square meters. But with that we saturated the market and had to lower the price and still ended up throwing away half of the crop.

We were also very early organic farmers, starting in 1977. At that time, organic farming was seen as a promise for small farmers in less favored areas. From 1983 onwards we developed organic sales to supermarkets through a cooperative (which we managed) which had mostly small growers as members. We expanded and at the peak years (late 1990s and early 2000s) we grew vegetables on around 7 hectares. It was hard work but it was also – kind of – profitable. Over the years, more and bigger farms converted to organic. Around 20 percent of the Swedish arable land is now organically managed and organic farms have an average size bigger than conventional. Imports also started to flow (Swedish vegetable production in general has a hard time competing with imports from countries with better climate and lower labor costs) and the prices of our crops were lower in the year 2000 than in 1980, while the value of the money was halved at the same time. Gradually the farm changed focus back into more local marketing.

Daikon radishes and organic farming are both good – but neither is a recipe for commercial success. Organic farming is certainly much better than conventional but it is no savior of small farms. As a matter of fact, the high costs for certification (for which I am very much to blame as being one of the pioneers in the organic certification business…), which is nowadays an integral part of the organic market, is proportionally a much bigger burden for small farms and the bureaucracy involved in compliance procedure also discriminate against small farms. The spread and success of organic also lead to a conventionalization of organic producers with less diverse production as a result.

Research in Brazil and Italy concludes that ” there was a significant and positive correlation between the crop richness index and the share of farm sales through alternative food networks.” But the researchers also pointed out that: ”proximity to densely populated areas is a necessary precondition for the development of the short food supply chains needed to stimulate the diversification of organic agriculture.” While I am certain that there are more possibilities for those living close to cities I am not convinced that this statement holds as a general rule in the long run. It is quite possible that local rural people will participate in alternative food chains. If the distance to major market hubs is great, the pressure of competition is much lower and potential customers may not have so many alternatives. In addition, peripheral areas are much more likely to engage in the “informal economy”.

Just a week ago, I visited farms in the region och Waginger See in Bavaria, not a densely populated area after continental European standards. Most of the organic farms I visited had a diversified production oriented to the local market. The one with the most diverse production was also a community supported agriculture farm, in German called Solidarische Lantwirtschaft. This farm, Blümlhof grows all kinds of vegetables and fruits, rye and dinkelwheat and has sheep cows, donkey, pigs, bees, chicken, horses and what not. They are three families working together and have some 50 “co-farmers” as they call the members of the CSA. Those commit 160 euro per month for a year at the time. For that they can take as much as they want of the harvest, the milk, the meat, the honey and the eggs pending availability of course, following the old principle “to each according to their needs”.

Elke and Hubert Hochreiter at Blümlhof, photo: Gunnar Rundgren

This kind of consumer-producer relations are based on cooperation and joint values and not on commodities and transactions. Food is not, should not, primarily be seen as a commodity to be bought or sold. To a large extent food is an expression of culture, solidarity and connectedness with the land. Food is also a human right. This also means that food takes the central stage in efforts to transform society. The main path towards true sustainability therefore lies in considerable changes in the market – or even more to develop distribution outside of what is normally called a market.*

Pickling cucumbers and preparing tomatoes for drying, photo: Gunnar Rundgren

There is not one single solution, but many. Increasing self-sufficiency in food and food preparation is another important step in changing our relationship to food. Growing, preserving, preparing, cooking and eating, taking care of the leftovers and waste of our food gives us control over a bigger share of our lives and at the same time, pulls a big chunk of the real economy out of market, away from competition and from the profit and machinations of corporations as well as the – often well intended but nevertheless stifling – meddling by governments. Growing, storing and preparing food, cooking and eating together with others is important parts of building a community. Even from an evolutionary perspective these are essential elements of being human and cornerstones of human cultures.

* I will not delve deeper into what a market is and what it is. Suffice to say that a transaction that involves money isn’t necessarily a market transaction and that a market has to have a certain level of competition and choice in order to qualify as a market, in my view. Admittedly, there is no straight-forward definition of what constitutes a market.