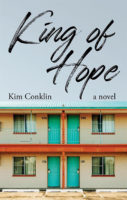

King of Hope

King of Hope

By Kim Conklin

Palimpsest Press, Oct. 2022, 289 pp., paperback, $17.95 U.S./$18.95 Canada.

Kim Conklin’s King of Hope is a dark and heavy first novel about a town plagued by nuclear waste. The town is a fictionalized version of Port Hope, Ontario, a community that served as a center for radium and uranium processing for decades beginning in the 1930s. Over those decades, radioactive material spread throughout the town due to leaking, dumping and the practice of using the waste as construction fill. The contamination eventually became the stuff of gothic horror—a ubiquitous, invisible threat capable of inflicting unspeakable harm.

Indeed, King of Hope is a work of gothic fiction: Southern Ontario Gothic, to be exact. Stories in this subgenre frequently involve desolate small-town settings shadowed by their buried pasts and haunted by grotesque horrors. They’re also often marked by a feeling of secrecy and a sense of physical, social or psychological displacement. Thus this subgenre is perfectly suited to a tale inspired by the tragedy of Port Hope.

The setting and characters are intricately drawn. Conklin’s fictional version of Port Hope is called Port Despere, and like the real place, it’s a quaint lakeside town known for its Victorian homes and natural beauty and wildlife. The story has an ensemble of interesting characters but focuses on just four of them. Our primary main character, Hart Addison, is the mayor of Port Despere and the publisher and editor-in-chief of one of its local newspapers. He’s also the owner of a ramshackle motel that’s never been opened and a home that leaks rainwater like a sieve. So committed is he to his paper and his work as mayor that he’s willing to forego such niceties as a roof that doesn’t leak and time with his wife.

The crumbling structures are metaphors for the characters’ inner states. Hart’s wife Ronnie, a transplant to Port Despere, is nearing a breaking point after years of being neglected by Hart and ostracized by the local community for her big-city ideas. Ronnie and Hart’s niece Lenni is also in crisis. Like many of the town’s children, she’s been battling severe illness. The hardest thing for her is being a 14-year-old girl without hair; and one of her few joys is spending mornings with Ronnie, who makes her feel good about herself with morning makeovers and photoshoots before school. Lenni is a lover of old classic movies, Ronnie is a professional photographer, and every morning Ronnie helps Lenni slip into the look and persona of a different actress from one of her favorite movies.

Our fourth main character is another newsman named Roger Guthrie. He does puff pieces to pay the bills but secretly hates himself for doing them, constantly longing for that big story that will both make his career and blow the lid off the Port Despere nuclear cover-up.

The plot unfolds over several days one fateful October. The moon is waxing as it moves toward a Halloween full moon; the sky and foliage are a wash of autumnal oranges, reds, golds and browns. Each of our main characters has a personal journey to undergo, while the town as a whole faces the momentous decision of whether to allow a third nuclear plant to be built within its borders. This new plant would recycle hot metal waste produced by the other two; but a company spokesperson admits there would inevitably be radioactive emissions. The townspeople are split on whether the new jobs would be worth the increased radioactive risk.

A major subplot involves Hart’s attempt to convince a big TV network to cover the results of a medical study commissioned by Port Despere residents. Frustrated by the Canadian government’s refusal to undertake its own comprehensive study, a local citizens’ group collected urine samples from a dozen people in Port Despere and paid for them to be analyzed at a specialty lab. Radiation levels turned out to be several times higher in study participants than in controls. The group presented these findings to the government and was again met with dismissal. Hart hopes the pressure of an international spotlight will change things.

Among other things, King of Hope is a brief window into the life of a small independent newspaper. Hart’s paper, the Guardian, is so tiny that he seems to wear just about every hat. In addition to running the business side, he goes around town reporting on breaking news himself. The paper is a passion project, one that brings in little money and few readers. It seems most people in Port Despere don’t want the fair and balanced journalism he provides; they simply want their preexisting beliefs confirmed. It’s a pointed commentary on the state of today’s echo-chamber media environment.

One way in which King of Hope is especially gothic is its rebuke of scientific rationality, for gothic fiction tends to emphasize the mysterious, the supernatural and the failings of scientific ways of knowing. The novel challenges today’s conventional wisdom that progress is inevitable, that technology is value-free and that science has the power to rein in those of its creations that happen to run amok. It also laments the modern world’s widespread dismissal of things that can’t be tested with science: “Prayer and luck might be authentic powers. Just because scientists had not catalogued, quantified, and reduced all of the forces of the universe yet did not mean that they did not exist.”

Radioactivity is itself a quintessentially gothic threat. To inhabitants of a pre-atomic civilization, it would have seemed like a malevolent supernatural force. It can’t be detected by human senses, yet it’s inimical to human and other life, and it’s much more insidious than a virus or other microbe. Its health effects often don’t show up for decades, they might not show up at all, and they often can’t be conclusively linked to their source. The abstractness and capriciousness of the threat from radioactivity lend it an almost Lovecraftian incomprehensibility.

My quarrel with this book has to do with style. Conklin uses a couple of different writing styles, and they don’t mix well. For the most part she uses simple language to convey a sense of solemnity, as befits such a grim story. But now and then a droll verbosity intrudes. Consider the following excerpt: “Without bothering to generate enough mental energy to register on a brain scan, he’d just run along with his tongue lolling…” Why couldn’t this have read simply, “Without thinking at all, he’d just followed along…”? At points the novel also has a tad more description than its story needs.

Yet these flaws, while distracting, weren’t enough to break my immersion in an otherwise engaging read. On the whole, Conklin’s novelistic debut is a solid one.

Teaser photo credit: Ganaraska River at Port Hope. By I, Hermann Luyken, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2252407