It’s really interesting to me that it took somebody like Theodore Roosevelt, who just reeked of testosterone, to put the idea of environmental protection on the public radar. He was one of the very few men in that time who could have because it had always been dismissed as a woman’s thing… kind of silly, sentimental, and anti-progress. – Professor Nancy C. Unger

Geoff Holland – How has gender dominance impacted the course of human history?

Nancy Unger – I think that is an excellent question, and it’s a huge question. I don’t want to reduce everything to gender dominance, but it has played such an enormous role. The reason I wrote my book Beyond Nature’s Housekeepers, American Women and Environmental History was not particularly as an environmental historian or wanting to talk about environmental issues, but really because this seems to be one topic that shouldn’t have anything to do with gender. We all breathe the same air. We all want clean water. I wrote this book to argue that gender dominance is so profound that it reaches into things that should be genderless. I’m arguing essentially that throughout American history, from the pre-Columbian period right up to the present, you take a brother and sister (same race, same class, same upbringing), and in the vast majority of cases, they will respond differently to the environment and environmental issues, based on what they’ve been taught about what it means to be a man or a woman. That’s how powerful these notions of gender are. They just seem to permeate everything.

GH – Are the oppression of women and the mindless exploitation of nature common threads of human cultural developments?

NU – I struggled with this question because I don’t think these cultural constructs are mindless. I can’t speak for every culture. I’m an American historian. But I was struck by this just yesterday. I was reading about Ruth Bader Ginsburg. She started teaching law in 1963. And she said, law school textbooks in that decade contained such handy advice as, quote, “Land, like woman, was meant to be possessed”. I mean, that thinking was reflected in law school textbooks in 1963. This oppression of women and exploitation of nature didn’t just kind of happen. They really have been constructed over time. There needs to be an enormous amount of effort to keep them going. That was one of the reasons I was so interested in the role of gender in environmental history because it really isn’t mindless. I think this is a result of a great deal of effort over centuries. You put it in terms of human cultural development. I don’t think this is something that has been in every culture, which makes it all the more significant to me… or all the more proof that it isn’t mindless. It doesn’t just happen that way. So, I’m not a big conspiracy theorist, but I think this is more insidious than just mindless. It really does take conscious effort to shape a human society that diminishes women and exploits nature.

GH – What role has traditional religion played in maintaining the dominance and oppression of women and minorities?

NU – Well, I’m not a religious scholar. I don’t know much about any religion, but particularly, anything that isn’t Christianity is really beyond my understanding, but I can certainly talk about it in American history. The Bible has been used to very specifically maintain the diminishing of women and minorities. I think particularly of St. Paul, who tells wives to obey their husbands and tells slaves to obey their masters with the reverence and awe that they owe to Christ. The Bible says that God gave men dominion over all the fish in the sea, the plants and the animals, and so forth. This is something that has been pointed to again and again and again, to move us away from the idea that this exploitation or oppression is mindless, or that it’s somehow natural. Both of those constructs are wrong. Religion has been used very successfully and very aggressively to oppress women and minorities in the United States.

I’m not an expert on other religions, but many Native American religions, particularly with the earlier traditions, did take an entirely different approach. So, it’s not like all religion is bad or all spirituality must somehow come back to being oppressive. I think it can be very uplifting. Many Native American religions and some other religions that do talk about giving dignity and respect to all living creatures, and so forth, can offer an antidote to some of the more poisonous, toxic ways that some religions have proceeded. There are also certainly deeply religious people whose Christianity really underlies their ideas about protecting the environment. So, you could pretty much make the Bible say whatever you want, depending on how you parse it. There is great potential for inspiration in Christianity, but in the past, it has been used in very negative ways. But it also has the potential to be uplifting. So, I’m not saying all religion is bad, or all traditional religions are bad. The potential is there for both great good and great harm.

GH – In the late 19th century, in America, women began to rattle the cultural page. And in 1920, women got the constitutional right to vote. How has that changed the cultural landscape?

NU – Well, unfortunately for me, on the one hand, women did get the vote, and that’s a huge gain, no question about it. But women have been so culturally inculcated in these very specific gender spheres. We saw the creation of The League of Women Voters just to encourage women to vote. So, I think that the vote, in and of itself, doesn’t really change the mindset all that much. But I do agree that we saw in that era the rise of the first feminist movement. What frustrates me, looking at the fight for the women’s vote, is that two arguments were put forward. One was, all people are created equal, and the second was that women should have the vote. That’s the whole feminist argument. You know, we have a government by the people, for the people…and aren’t women people? Unfortunately, that argument didn’t get very far. With most men and with most women, the compelling argument was more that women should have the vote because they were the mothers and the nurturers, who weren’t ruled, as men “naturally” were, by avarice and the obligation to provide. So, I get a little impatient when women getting the vote is presented as this huge success story on the ladder up for feminism, but no question the vote was an important step. However, gender dominance was so entrenched in the early 20th century that I don’t see the vote as really shaking that loose. It took a much more radical approach from more radical women and a few radical men to really begin to challenge those deeply imbued notions of what it means to be a man and what it means to be a woman.

When I was in graduate school, the big word was deconstructionism. And it just drove me crazy. I mean, what does that mean? But the idea that these cultural constructions are just that…they’re constructed over time…these ideas that women are naturally sentimental, and men are naturally stronger emotionally. It took me a long time to really understand how important it was to see how those cultural constructions developed over time. I’m teaching women’s history this quarter. It’s really exciting to watch these students as the quarter goes along. At first, they think it’s intellectually interesting, this early American women’s history. Then, as we progress with history, and we start getting closer and closer to the present, it’s like, wait a minute, they start to see how this gender bias impacts their own lives. As an educator, it’s really exciting to see the students’ recognition emerging. I’ve strayed pretty far from your original question. What I really want to emphasize is that to understand both women’s history and environmental history, you really have to take a deep dive into these cultural biases. The deeper I have been diving, the more it’s profoundly evident to me, as we discussed earlier, how much of our culture is created intentionally over time — so successfully, that these gender-cultural constructs have been very hard to challenge. But gender bias needs to be deconstructed. I mean, clearly, we’ve come a long, long way. But there’s still a lot of work to do.

GH – How important has access to education been to achieving equality for women?

NU – Well, I’m kind of biased on this. I’m an educator. I believe in education. I think it’s just so profoundly important. I’m part of the first generation of my family to go to college. Neither of my parents was college educated, but I thought they were very bright people. So, I don’t think you have to have formal education to do well and to think wisely, but it sure helps. You can’t exaggerate the importance of education. I look at my mother. She will be 100 in January. She often talks about how she might have been had she been educated. She was widely celebrated in her family because she was the first to graduate from high school. Education is really, really important because once you learn something and know how to process information, you can’t unlearn that. It was Gloria Steinem who said the truth will set you free, but first, it will really piss you off. I think that’s true. Education helps you to challenge accepted ideas about the world. You start to ask, why are things that way? Could they be different? Could they be better? What would a better world look like? When I look at some of the women in the environmental movement I’ve written about, so many of them were not formally educated, but they were educated in the sense that they knew their community, they knew the people around them that were asking the right kind of questions.

Any kind of education is going to be good, but I’m a big proponent of formal education, of having people help you to learn how to process ideas critically — to think critically, and to communicate your thoughts effectively. Those are really important skills. Some people have them without ever setting foot in a classroom, but most of us benefit a lot from having teachers or mentors guide us along. That certainly was the case for me, and my students tell me it is for them as well. When I get depressed, I take out a file that I keep in my office. It’s my “this course changed my life” file. It’s letters from my students telling me how my class changed their lives because, they say, “it really taught me to think critically, effectively,” and so forth. I don’t think you can overstate the value of that.

I work with a lot of really well-educated people. Some of them are brilliant, and some of them are not so much. So, I’m not suggesting that formal education is the key to all things. I do think when women are barred from various professions, and when women can’t become doctors, lawyers, professors, business leaders, and so forth, this is a powerful way of oppressing them. Education is of great value in and of itself, but professional training is a way that allows women and minorities to really compete economically, and to be at the table where decisions are made. So, education in all forms and at all levels…that’s the key to the kingdom as far as I’m concerned.

GH – What role have women played historically in fostering environmental stewardship?

NU – I would say one of the things about that question that troubles me a little bit is this notion of stewardship. A lot of that comes from some of those religious traditions that we’ve talked about. I read a lot of Carolyn Merchant when I was just beginning to really think about women and the environment, and stewardship is not the word that I like to use. She uses the word partnership. I like to use that word as well. Stewardship, to me, still suggests a kind of superiority. We’re stewards over something else, as opposed to being in a partnership, with nature, and with other people. I get the gist of your question, but I wanted to point that out. I would say that in many, many places around the world, women really were spearheading environmental consciousness because they were the ones closest to the Earth, and they’re the ones who carry the water, who search for fuel. They’re the ones who give birth or experience miscarriages and stillbirths. Men and women tend to do different things in society. In some ways, this has allowed women to have a certain kind of authenticity on environmental matters.

Look at the United States, where many women felt qualified to take on environmental issues, ironically because of these prescribed gender ideas that have held firm in the United States for many, many generations. The role of male humans is said to be the providers. They have to go out and make a living in the wilderness or the urban jungle, and they don’t have the luxury of environmental thinking. They can’t sit around and ponder the consequences of their actions; they’ve got families to feed and stuff to do. Women were told they were more sentimental, thinking more about future generations because they had the luxury to do that. In many ways, these gendered ideas did relegate women to a very domestic sphere. At the same time, a lot of women began taking that role really seriously and used it to empower themselves. In some cases, it may have been just so they could be heard, but others, I think, were very sincere about what they were talking about. Yes, of course, women have to be involved in environmental issues. We have to be concerned about clean water because we’re the ones who are cooking and taking care of our children. We have to be concerned about the purity of food and medications. We have to be involved in wilderness protection because we can’t trust men with this. After all, they are so ruled by this profit motive. Gender roles were a kind of prescription designed to keep women separate and severely limited. In a way, it kind of backfired. It contained the seeds of its own destruction.

When I was on a book tour with Beyond Nature’s Housekeepers, in the Q&A sessions, there were usually one or two women who were very critical of me, very angry, because I was saying that women were not innately more environmentally attuned than men. They felt that this was one of the great strengths of being a woman; that being a woman was their environmental credential, because they were mothers and nurturers. So, I think that many women, at least throughout American history, really believed, or at least said they believed, that their prescribed sphere as a woman gave them environmental authority.

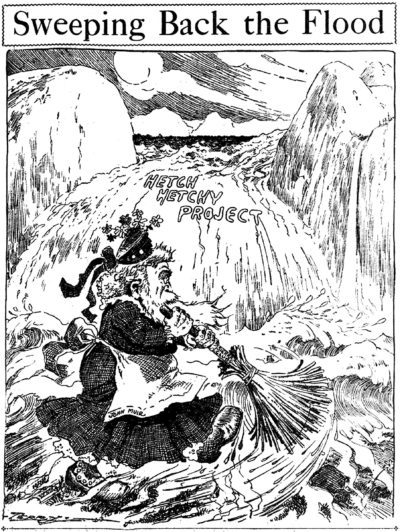

I have a cartoon in my book. It’s the great naturalist John Muir, and he is trying to stop the flooding of Hetch Hetchy Valley. It’s an early 20th-century political cartoon published by the San Francisco Call, and it’s lampooning Muir as this silly man who’s trying to sweep back the waters of progress. And so of course, he’s in drag: he’s wearing a little flowered bonnet, he’s wearing a dress, and he’s got this little broom. If you want to diminish a man who’s involved in environmental protection, you reduce him by making him effeminate. It’s really interesting to me that it took somebody like Theodore Roosevelt, who just reeked of testosterone, to put the idea of environmental protection on the public radar. He was one of the very few men in that time who could have because it had always been marginalized as a woman’s thing… kind of silly, sentimental, and anti-progress.

Cartoon questioning John Muir’s masculinity for fighting the Hetch Hetchy Dam in Yosemite National Park, built to bring water to San Francisco. San Francisco Call, December 13, 1909.

GH – What does your research reveal regarding the LGBTQ community’s affinity for caring for nature?

NU – This was so interesting to me. Consider this: in 2011, a Harris Poll was indicating that 55% of LGBTQ plus people, compared with 33% of straight adults, cared a lot about green issues; that 48% versus 25% considered the environment while shopping; 45% versus 27% placed a high value on a political candidate’s stance on green issues. So, I thought, this is so interesting; why is this? Some of it, I think, is that LGBTQ people understand what it feels like historically to be devalued and have paid the cost for that. So, they understand what a problem it is. I’ve done a fair amount of work on lesbian alternative environments. You may recall, in the 1960s, and 70s, there were a lot of back-to-the-land movements. It’s like, we can’t seem to change American society from within, so let’s just start fresh, do things differently. There were a lot of lesbian alternative environments, especially in Oregon, but really, throughout the country, in Canada, and some other places. They said, look, we can’t wait to reform the inequities in gender status. What if we created places where lesbians could be who they were, be comfortable, and just reject all cultural values that deny their humanity. Let’s think and live differently. Let’s reject Christianity, reject capitalism. Let’s reject this whole culture that is wasteful and destructive; reject the idea that our value as humans should be measured by how much stuff we have. So, they created this tiny house movement kind of thing. They’re recycling, and they’re really trying to live off the grid as much as possible.

Most of those people in the back of the land movement didn’t last there. Living that way is just too much work. It’s too difficult. But they did bring back into more mainstream society some of those values and those efforts to live really differently.

So, when I look at some of the gay men’s groups and these lesbian alternative societies, I see people thinking outside the box and connecting sexual oppression and gender oppression with the oppression of nature. They’re encouraging the culture to not do all that negative stuff. They’re asking, “What does a truly equitable society look like?” They’re standing for some pretty amazing, life-affirming cultural changes that they have made a serious effort to model.

GH – What can we learn from indigenous people, when it comes to living in harmony with nature?

NU – Well, my knowledge is very limited on this. And it’s always dangerous when you’re talking about Native Americans in what is now the United States because we’re talking about whole different peoples, different languages, and different ways of living. So, I’m going to be painting in very, very broad strokes here. But what really strikes me is that thing I was talking about earlier: the emphasis on partnership with nature. That really appeals to me, this notion that people are not superior beings. We’re a part of nature. Just one part of a larger nature. I’m convinced that thinking that way can have a profound impact on how we live.

The other thing is – I get impatient when I hear this “Native Americans lived so lightly on the land.” Well, yes, they knew and still know that they are, we all are, part of nature. We are not separate from all of the non-human living nature. What I think Native Americans did that really is important is to focus on sustainability. They didn’t always “live lightly on the land,” but when the soil or local hunting or fishing grounds were depleted, they moved on. Today, we’ve still got people who are farming, and they farm and farm and farm the same crops year after year. Sooner or later, the soil gets depleted. Traditionally, Native Americans who farmed, rather than doing the backbreaking work of replenishing the soil through fertilization, would simply pack up and move. Packing up and moving means you can’t have a permanent house and you can’t have a million possessions that you’re going to be bringing along. You have to live pretty simply. The environmental historian William Cronon has said that Native Americans “lived richly by wanting little.” Crucial to “living richly” was keeping the population numbers low. This is something a lot of your readers understand, but my students really don’t think about population as being such a crucial environmental issue. Native Americans made conscious efforts to keep their populations low, so they could stay mobile, and they could move on to some place where the land and resources were fresh and ample. So, all of life could renew itself and thrive: the land, the resources, the people. And I think that comes from that respect for nature as a partner, not an entity to be dominated, and from the emphasis on small, mobile populations.

GH – When it comes to sexual expression, women are still not free. Is a gender-equal world even possible as long as consensual expression remains subject to policing and moral judgment?

NU – The answer to that is, No, it’s not. There has been forward movement on this issue. Just to illustrate what we’re talking about, I have asked some of my Women’s History students in 2022, what do you call a younger single man on a college campus, who has a lot of sex with different women? The answer is always something like, he’s a player, he’s a stud. Then, the question becomes what do you call a young woman who has a series of sexual partners, the answer is always the same: a slut. There’s just no question there’s a double standard for gender and sexuality. I do think it’s getting better. Even though there are still those sorts of stereotypes, in my lifetime we’ve come a long way from the old “boys will be boys” excuse for sexual violence. So much of that change has to do with the advent of reliable birth control and abortion. It really is no longer just that biology is destiny. Now, young women can have the same kind of freedom to experiment sexually as young men have, without worrying about becoming pregnant.

There has also been a meaningful change in things like rape legislation. When I was young, if a woman said she’d been raped, and she went to trial, her entire sexual history, could and was, brought up in the courtroom. The unspoken question was, “What was it about you that brought on this rape?” Birth control and abortion have had a role in giving women more freedom to express their sexuality as they wish. But obviously, with Dobb’s decision, this is coming under attack. It continues to be a rubbing point with a lot of religious communities. But sexuality is such a core thing. It’s so important to who we are. Until there really is equality on this human right, I don’t think there’s going to be true freedom; until we all have the same rights, regardless of gender.

GH – Trends suggest that humanity, in the early 21st century, has achieved something akin to a global collective consciousness. Is that a requirement for shaping common purpose in a future that is life-affirming and sustainable?

NU – I agree absolutely that such consciousness is a requisite to that kind of future. I wish I was more confident that global collective consciousness is taking shape. I worry when I look at this country and see how deeply divided it is. That makes me nervous. On the other hand, we are connected in amazing ways through the global internet. Environmental issues in particular are really getting traction, in ways they never did before. When I was young, there were smoking and non-smoking sections on an airplane. How stupid was that? If you have a smoking section in a confined space, then everyone in that space is essentially smoking. It’s the same thing as what our Earth’s collection of nations is doing environmentally. I do see an increasing awareness that we can’t just do our little provincial thing and think it’s not going to have a global impact. I also see the collective consciousness phenomenon coming along. There is increasing recognition of human-caused climate change, and this awareness is happening around our world. That’s absolutely crucial because people have to see how things have been constructed over time in order to thoughtfully deconstruct them in a way that’s life-affirming and sustainable. My focus is higher education. And this is an arena where we’re beginning to see this understanding.

Education is one of the ways this global consciousness can be built. When I started teaching, most students had to take a history course, and they took Western civilization because that was the easiest way to meet that requirement. Now, at my university, and I think most universities in the United States, and in many places in the world, you can’t do that anymore. It’s like, no, there’s a whole Earth out there. Our history majors have to take courses in different areas of the world, no matter what their particular area of interest is. Even if they want to be American historians, they have to have some understanding of Asia and the Middle East, and so forth. The provincialism that once prevailed is changing when it comes to education. That is encouraging cultural change in a lot of ways. We see it in the United States in K–12 education as well. Today there’s much more emphasis on our place in the larger world and getting people to think globally. But old habits die hard, especially the old habits that make some people a lot of money and give them a lot of power. So, I do see a global collective consciousness emerging. I just wish it would hurry up and find a place in everyone’s mind. It’s coming up against some really, really powerful cultural forces.

My training focused on the first industrial era, starting in the late 1800s. If you had told people, in the peak of that time dominated by enormous, powerful businesses riddled with corruption, that progressive reformers were going to meaningfully change things by creating Pure Food and Drug Laws, passing safety legislation, breaking up trusts, and demanding environmental protection, nobody would have believed it. So, if we can shape a collective will that is based on a worthy common purpose, amazing things can happen. But there remains so much organized and powerful opposition; people who have a lot to lose in the short term from the good kind of change. These are not people who are going to give that up readily. So, I’m happy to see this growing, planetary-scale awareness and cultural progress happening, but I’m only cautiously optimistic that we’ll end up with a world that is life-affirming and sustainable anytime soon.