Ed. note: This article first appeared on ARC2020.eu. ARC2020 is a platform for agri-food and rural actors working towards better food, farming, and rural policies for Europe.

Farming is a job that you live. For farmers, succession is more than just passing on the physical farm, land and buildings. Once you build up a successful farming enterprise, how do you ensure all of that knowledge and experience is not lost? It’s a question that preoccupies all of the farmers who participated in the “Nos Campagnes en Résilience” project.

In France, the stakes are high: a quarter of farmers will reach retirement age in the next five years, according to Terre de Liens.

Part two of a series analysing the hot topics around transition, by the “Nos Campagnes en Résilience” team.

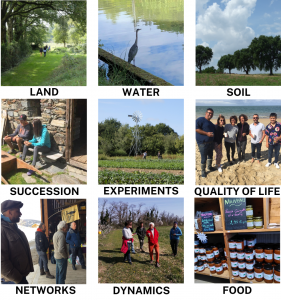

Succession is one of the nine common themes that emerged from our interviews with rural actors

Succession is often a family affair. The farm is passed down from generation to generation.

“This was the family farm, belonging to my parents, and before them my grandparents. Where we are today on the farm is one moment in a long progression that started a long way away, and the idea is that the farm, as we keep it alive today, can be passed on in the best way possible and stay alive in the best way possible, with the maximum number of people working on this farm, in this place.”

Mathieu Hamon, dairy farmer

The farm conveys meaning, a common history that evolves over time with people and their lives. It’s not only inheriting buildings or land; it’s also bequeathing a cultural family heritage. The emotional dimension is important, as are the values and knowledge passed on. Although there may or may not be continuity in the choice of farming practices from one generation to the next, which can be a fear for the previous generation.

“They were afraid for us because it was a model that didn’t exist. But they trusted us”

Marion et Benjamin Henry, mixed farmers

This cultural heritage is passed on intuitively, and serves as a foundation for the future farmer.

However, all this is ignored by the legal framework in France. Succession is often limited to the market value set by the price of the land and the farm’s activity. This shortsighted view of succession is a source of much frustration and resentment. Yet again, the human dimension is put on the back burner, relegated to a sub-category within the predominant economic model. We desperately need a paradigm shift in the approach to succession.

When the farm is passed on to a person outside the family, the transfer tends to go more smoothly. Even more so when the process is well thought out in advance: whatever has been acquired or built must be transmissible.

“The previous generation had a perspective of succession, which facilitated our installation”

Sylvie Chapeau, dairy farmer

The legal structure of the farm, its size, facilities and viability must all be factored into succession. But it’s more than that, as Sylvie told us: there is also the organisation of the farm and the philosophy behind it. For Sylvie, two things were essential: no dehorning, and the grazing system. These were the determining factors for her to undertake this new adventure.

An interesting tool for succession in France is the farm cooperative or GAEC (Groupement Agricole d’Exploitation en Commun). This legal structure means that associates can join or leave the farm by buying or selling shares in the cooperative. However, many obstacles remain – not least administrative.

“It’s too complicated to get into and out of farming. With all the economic and administrative hurdles, it’s a real obstacle course.”

Benjamin Henry, mixed farmer

Debt is another hurdle. Driven to invest, small-scale farmers sometimes find themselves in complex financial situations that prevent them from passing on the farm.

“You repay the land your whole career, your land is now capital and you sell it or you remain the owner and rent it as many farmers do today”

Marion et Benjamin Henry, mixed farmers

This merry-go-round of investment has to change: policymakers need to understand that investment supports push farmers into a runaway trajectory of purchases and loans that in some cases leads to ruin?

The question of succession stands. In an attempt to get the issue on the political agenda, farmers’ networks have tried to raise awareness and introduce it into the public debate. Currently there is no legal framework in France that facilitates handover.

Citizens’ groups, local authorities and farmers’ groups have seized on the issue. For these groups, succession is key to keeping farming – and therefore local territories – alive.

Turning to the social and solidarity economy, they are exploring different legal structures, for example the SCOP cooperative (Société CoOpérative de Production). Within a SCOP structure, the cooperative would consist of the farm itself, rather than the associates, which would facilitate handover of the farm. A SCOP would also offer better social protections for the associates.

Succession is about more than the farm

Education plays a central role in the transmission of knowledge and skills. In France, agricultural education comes under the remit of the Ministry of Agriculture. Many of the farmers we interviewed objected that the teaching is outdated and out of touch with the reality on the ground, and fails to incorporate agroecology.

“As time goes by, we realise how much we have developed skills that don’t come from our training. At most our skills come largely from our general training to open up to things, I learnt things I would never have learnt.”

Mathieu Hamon, dairy farmer

Agricultural training is based on conventional models. Educators open to new possibilities remain the exception. However, new packages of measures to support the ecological transition offer a glimmer of hope for a rethink.

Agricultural students have to complete several hands-on traineeships on partner farms. This is an opportunity for young person and farmer to share and learn from each other.

“We learn alongside them”

Fabienne Corbé, farmer-baker

By receiving trainees, farmers have the chance to pass on their day-to-day experiences, successes and failures, and to proactively support their future colleagues. The farmers are motivated by the desire to contribute to the evolution of the profession and practices.

“I have the assurance of my experience. When I get a group of trainees, I tell them: ‘You bought books. Good. You’ll be able to light a nice fire with them and depending on where you land, you’re going to adapt your plan. You won’t adapt it to the books you’ve read.’ You can’t compare one place to another.”

Stéphane Airault, vegetable grower

The empirical knowledge of farmers is an asset that contributes to the dynamic of the territory, and can ensure successful succession.

Knowledge sharing between peers

All of the farmers we spoke to stressed the importance of exchanges of practices and knowledge between peers. These less visible forms of knowledge sharing include informal or independent learning, and peer-to-peer learning through organised networks such as the CIVAM or CUMAs, with contributions from experts.

By providing opportunities for forging connections and learning, they contribute to changes in the agricultural and civic practices of these rural actors.

“Our training is more related to the networks we’re in now, to the things we’ve focus on over the years, and to our experience”

Mathieu Hamon, dairy farmer

The French state is currently putting in place new measures to promote lifelong learning, particularly for private sector employees. In this sense, small-scale farmers have been ahead of the game for many years, organising to ensure the transfer of knowledge by making good use of the quintessential tools at their disposal: existing networks, exchanges and mutual aid.

Succession is a sweeping question. Passing on the farm, and transferring the associated knowledge and experiences through formal training and peer-to-peer learning: we’ve examined each of these aspects individually, yet none can be dissociated from the other. Although an issue that is little discussed, succession bridges the gap between generations. The link between the past and the future, it allows us to envisage the future – in continuity or forging new paths – informed by previous failures and successes.

Don’t miss part 1 in the Rural Realities series: Feet on the Ground in the The Battle for Land.

Part 3 of the series will examine the freedom to experiment since, although farms are life-size laboratories, their expertise often goes unrecognised.

Nos Campagnes En Résilience is ARC2020’s project to support and connect initiatives around rural resilience in France. Visit the project page here and follow us on Instagram, LinkedIn and Facebook. If you’d like to get involved, contact our project coordinator Valérie Geslin.

Teaser photo credit: The next generation, at a meeting with farmers participating in the Nos Campagnes en Résilience project, French Alps, July 2021