Indigenous knowledge offers invaluable insights for how to approach climate change. This article describes a tool called the Tribal Adaptation Menu that provides a set of concrete, practical strategies, approaches and tactics for how to incorporate indigenous thinking into planning, policy, research and interventions for researchers, policy-makers and practitioners. It also describes the fundamental shifts in thinking and relating to the natural world that offer a key to effective climate adaptation.

The illustration on the cover of the Tribal Adaptation Menu portrays the relationships among all beings.

Indigenous knowledge for climate change

Indigenous people developed deep knowledge about their environment that they built through relationships with land and with place over hundreds and often thousands of years. They have learned how to live off the gifts of the earth and take care of them so that they will be healthy for many generations to come. This knowledge offers another way of seeing and understanding the world, one that is necessary to address climate change. Now scientists, governments and communities are finally recognizing that taking action to adapt to climate change is urgent and an increasing number of people are looking to indigenous knowledge for insight.

If you live in a place where indigenous knowledge has been buried under centuries of colonial culture, the idea that you could use it to adapt to climate change may feel vague. The Tribal Adaptation Menu (TAM) is a guidebook of sorts that translates indigenous knowledge from tribes in the Great Lakes Region of North America into concrete concepts, strategies, approaches and tactics. It is called an ‘adaptation menu’ to highlight the indigenous approach of “observation, recognition, deliberation and adaptation while facing environmental change, in contrast to the Western perspective of exploration, domination, exploitation and extraction” (TAM, page 9).

Climate change often promotes a sense of urgency. Building the relationships with humans and with non-humans necessary for climate adaptation takes time.-TAM

The TAM is made up of a series of strategies, approaches and tactics aimed to guide action. The idea of the menu is that it is a collection of actions from which you can choose the ones that are relevant to your context, either as a group in a step by step participatory process or as an individual. The first version of the TAM was developed based on Ojibwe and Menominee (two tribes in central North America) perspectives but designed to be adaptable to other indigenous communities.

This brilliant tool was developed over two years by a diverse group of people representing tribal, academic, intertribal and government entities in the Great lakes area of the US (Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan). Some of these authors have been offering workshops to teach people about it; the TAM is so much more than a document. Putting it into action requires a shift in thinking and how we relate to others.

The authors of this post, Jessica and Annette, participated in one of these workshops, together with a group of academics from the University of Minnesota, and practitioners from a diverse range of organizations, all working in some way to protect wild rice (manoomin), in which we were able to experience the TAM in action. We felt that it was well worth sharing our experience.

The workshop took place on the banks of the St. Louis River in Minnesota in June 2022. It was attended by a diverse group of people, all working to protect wild rice.

Indigenous knowledge is built on place-based relationships and reciprocity

On the banks of the St. Louis River, on a cool June morning, participants representing academia, non-profit organizations and tribal entities from the region formed a circle near the water and participated in a prayer of gratitude. An elder shared with us an Anishinaabe teaching about the way that plants, animals and the natural world do not need humans to survive, but humans do need the natural world to survive. Relating with the natural world on the basis of this simple concept entails humility and respect. The Anishinaabe understand their place in the world as one requiring reciprocity– giving back and taking care of the natural world so that humans can continue to survive.

The first day of the workshop was dedicated to just that: building and understanding relationships. Rather than diving into the main content of the workshop, we spent time getting to know each other, our work and how we relate to manoomin (wild rice). Without this step, one that is often skipped in scientific and management meetings, we could not fully appreciate or understand each other in order to do meaningful work together.

The first day was dedicated to developing relationships and getting to know each other.

After hearing from everyone at the workshop we spent time unpacking what is normally not spoken about: the values that drive the organizations working to mitigate or adapt to climate change. We studied the mission statements of the University of Minnesota (UNM) and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR). The words use of resources for commercial purposes, recreation opportunities, academic excellence and management were dominant. Both organizations have mission statements based on instrumental relationships with nature.

The words explicitly lacking in the UMN and DNR mission statements were those indicating responsibility, such as ‘care for’, and ‘respect of’. It became clear that extraction, use for human benefit, and prioritizing economic profit were primary values driving the organizations. What would happen if these organizations were to replace ‘management’ with ‘stewardship’, ‘use’ with ‘reciprocity’, ‘resources’ with ‘gifts’?

These reflections are key to understanding what indigenous knowledge can offer to climate science. The first part of the TAM document describes some of these guiding principles of indigenous perspectives in depth, and only then how to apply them.

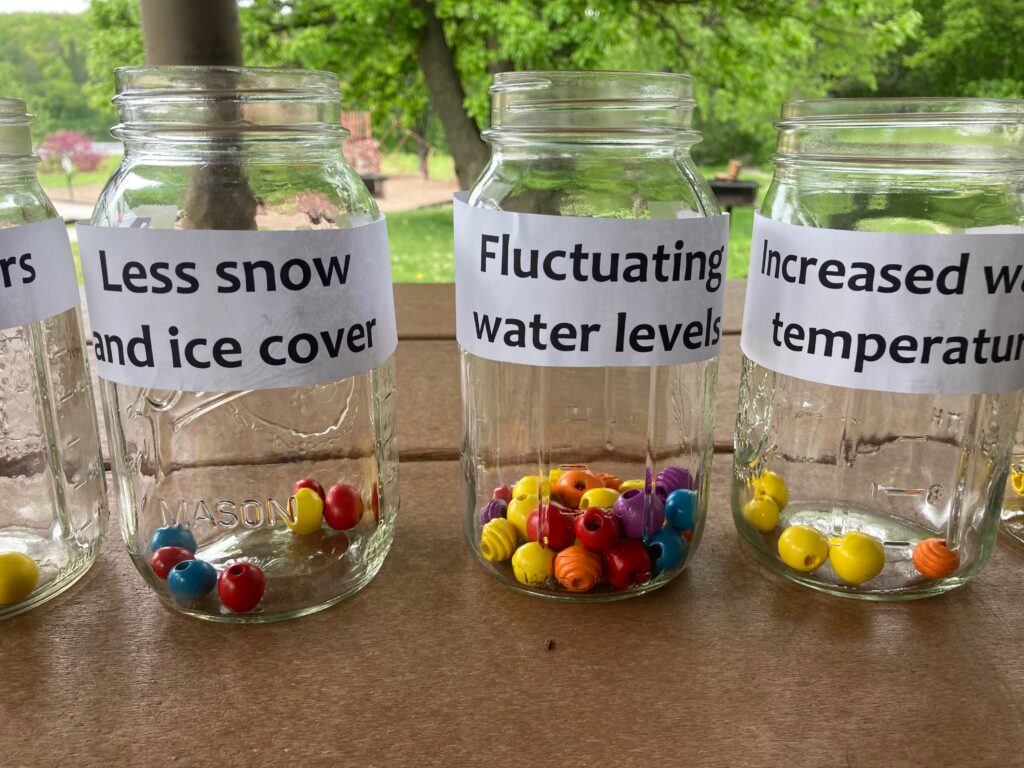

In small groups of people working different cases, we analyzed the climate factors affecting the stands of wild rice and voted with colorful beads.

TRIBAL ADAPTATION MENU

In total there are 14 strategies in the menu. The original 11 strategies were adapted for Indigenous communities and three new strategies were added. These three strategies, outlined below, are in addition to the climate adaptation strategies first developed by the Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science.

The first strategy is: Consider cultural practices and seek spiritual guidance.

- Consult cultural leaders, key community members, and elders.

- Consider mindful practices of reciprocity.

- Understand the human and landscape history of the community.

- Hold respect for all of our relations, both tangible and intangible.

- Maintain dynamic relationships in a changing landscape.

This strategy is focused on considering the community members and their relationships with the landscape being evaluated. In a western based approach community members and leaders may be invited to participate, but are often not consulted in a manner that recognizes their cultural relationship to the land. Taking the time to consider a more nuanced understanding of relationships, and hold respect for a different perspective is important in moving forward in a good way. Viewing all life through a lens of reciprocity and a responsibility to future generations changes individual and collective perspectives on adaptation for the future. This strategy also calls attention to the relevance of understanding historical processes and dynamic relationships.

During the workshop we engaged in collective problem solving, reviewing all of the strategies in relation to a set of cases brought forward by participants. All of the cases focused on different approaches to protect wild rice (manoomin). With the TAM as our guide, we quickly came to realize what most of our projects were missing. In some cases, lack of familiarity with the communities kept us from seeking out elders, asking about history or whether there were ceremonies that should be performed before initiating work. The facilitators encouraged us to act intentionally and to consider other voices, including our non-two legged relations, suggesting that we open our hearts and minds to a wider understanding of who our relations are. They challenged us to hold respect in ways that might feel unfamiliar.

The second strategy is: Learn through careful and respectful observation (gikinawaabi).

- Learn from beings and natural communities as they respond to changing conditions over time.

Based on a verb (gikiniwaabi) that doesn’t exist in English, this second strategy encourages climate planners to observe in a careful and respectful way. In a western centric worldview action is often considered first, with higher priority given to costs and time than relationships and understanding. Westerners lead with the head, and not the heart, and even discount other senses when tackling complex problems. Logic and analysis are typically dominant in tackling complex problems, while heart and relationships are not seen as relevant.

This strategy urges people to observe and learn from the natural world, in a way which may be unfamiliar to many. Much of the way that western science understands the natural world has come from looking at individual components of the environment in a manner that dissects rather than makes connections. Reaching out to knowledge keepers from Indigneous communities who are more skilled in this careful observation broadens this understanding of places.

A number of participants shared their difficulties with this strategy in the contexts of the institutions they work in that require quick responses and value scientific-rational-empirical based solutions, rather than one based on deep observation. As a group we discussed the limitations of short funding cycles and the demands of reporting to show short term impact.

Each group chose strategies, approaches and tactics from the TAM to apply to our particular case and presented these to the larger group.

The third strategy is: Strategy 3: Support tribal engagement in the environment.

- Maintain and revitalize traditional relationships and uses.

- Establish and support language revitalization programs.

- Establish, maintain, and identify existing inventory and monitoring programs.

- Establish and maintain cultural, environmental education, and youth programs.

- Communicate opportunities for use of tribal and public lands.

- Participate in local- and landscape-level management decisions with partner agencies

One of the tactics used in the colonization of North America, was separation of indigenous people from their land, water and food, and with it the traditional knowledge that informed those relationships. The main concepts behind this strategy is to help develop day-to-day relationships with the environment in a range of ways, and to bring excluded voices to decision making space. Environmental education, youth engagement, communication about opportunities for getting out into the woods to harvest, gather, fish or hunt and the revitalization of traditional knowledge are key actions. Others include inventory and monitoring programs to facilitate community participation in collective analysis of climate change adaptation. Looking beyond the immediate, so-called-direct solutions to the ‘climate problem’ and addressing the core disconnection to the environment is an important place to start.

Attempts to exclude, assimilate and destroy Indigenous culture have impacted tribal communities in long-lasting and destructive ways. Language and revitalization of traditional culture are a means for reconnecting with the land. Recognizing how laws have been used to sever communities from their lands means that it is important to listen and rebuild trust as part of making room for indigenous perspectives at the negotiating table. However, structural power relations and project time constraints are impediments to bringing a wide array of voices to work on the challenges that climate change presents. If lawmakers, practitioners and academics are serious about bringing excluded voices to the circle to tackle climate challenges, it is fundamental to consider the conditions of that participation.

One concept that is often overlooked is the importance of dedicating time to processes. Climate change often promotes a sense of urgency but building the relationships with humans and with non-humans necessary for climate adaptation takes time (TAM, page 11).

SHIFTING THE ROLE OF ACADEMICS, PRACTITIONERS AND SPEAKING FROM THE HEART

Learning from indigenous knowledge for climate solutions requires also doing research and designing practical interventions in a different way. This is not easy with the institutionalized processes currently in place. The Tribal Adaptation Menu offers practical approaches for integrating indigenous perspectives. Using these strategies and key teachings each person and organization can begin to incorporate small (or big!) changes into future meetings, during the design of new collaborations or grants, and the writing of articles and reports. Speaking from the heart, incorporating the values of reciprocity, humility, respect, and deep observation is already a big step forward.

CHECK OUT THE TAM YOURSELF!