“Why should we destroy the economy to prevent just 2 degrees of global warming? That can’t be the reason for the restrictions. They just want to control us.” Have you heard that recently? I have, including from people who previously expressed concern about the environment. That is despite recent and unprecedented climate disasters in Pakistan and elsewhere. One reason such scepticism on global heating can spread today is because of how bad communications have been. Strategic communications is a specialist field in my work as a Professor and political advisor. Alarmed at the persistence of arguments against bold climate action, I decided to turn my attention to climate communications and share with you what I believe to be three massive mistakes.

If we are told by scientists that the world has already warmed by 1.2C degrees, how bad do we feel, really? Intuitively, we might think of daily maximum temperatures, where an extra 1.2C degrees is not a big deal. Our feelings might shift a little when we realise that is an average for night and day, summer and winter, and over land and sea. But still we have nothing to compare it with. Such as by knowing it was an average of 13.6C degrees back in 1850, before rising to the current 15C degrees. Without this extra information isn’t it understandable that people don’t feel the truth of the dramatic changes already underway? Especially if they are faced with policies that will affect their cost of living. Sometimes even experts get confused with these averages and make outlandish claims that agriculture could cope with a 15C degree global average rise. Which, by the way, is the current climate of the Western Sahara.

As I understand it, humanity is already in a situation of global crisis and tragedy. In only 200 years, industrial activity has increased world temperatures by an amount equivalent to 20% of the total range experienced since the first homo-sapiens walked on Earth over 200,000 years ago. That is an influx of energy that is messing with weather systems, damaging both wilderness and agriculture. The speed is unprecedented. In my 50 years on this Earth, our planet has been warming 170 times faster than it was cooling over the previous 7,000 years. For the rest of this century, rises will likely be hundreds of times faster than any period of warming in the last 65 million years. Ecosystems cannot evolve fast enough to cope with that pace of change.

That is shocking, and so it should be. But by sugar-coating the latest science, emissions trends and limitations of technology, some experts are making people doubt such emotion. Although we can appreciate some experts do not want us to lose hope or focus, this ‘climate brightsiding’ of the public is both inaccurate and counter-productive. It is inaccurate, as there is some inevitable atmospheric warming ahead, due to how much additional heat is already within the oceans and how much carbon is in the atmosphere. In response, some say that technologies like mechanical Direct Air Capture of CO2 can help. However, their low effectiveness and high energy demands should not give us confidence. In addition, recent research has debunked the argument that economic growth can be sufficiently decoupled from resource consumption and pollution so that the world economy might keep growing without terrible consequences.

It is also counter-productive to imply climate activists are becoming overly negative or fatalistic. Both psychological research and the testimonies of activists shows us that anticipating difficult futures is not demotivating. Instead, research finds that believing that machines, entrepreneurs and leaders will sort it all out for us is actually demotivating.

Alarms like the recent United In Science report from multiple United Nations agencies may help the ‘brightsiding’ to recede. But as impacts worsen, atmospheric carbon increases, and the science becomes more troubling, there is the risk of yet another mistake in how leaders think and talk about climate. Oftentimes, when leaders realise that the systems they administer are damaged or threatened, they respond with draconian decisions that make matters worse. For instance, brutal approaches to law and order in the wake of disasters, or scapegoating people to distract attention away from themselves. With climate, in future could such ‘elite panic’ inspire leaders to curtail personal freedoms to appear decisive? That could lead to massive resistance from populations, who might then regard action on climate as synonymous with coercive power, rather than collaboration. Instead, the future of communications on the climate crisis must focus on freeing all of us from the systems that drive us to dump costs onto others and nature. Let’s recognise and work with the fact that most people want to do the right thing if they aren’t forced by circumstance to do otherwise. And let’s communicate better about why and how to reduce contributions to planetary heating, before that devastating 2C degree global average is reached.

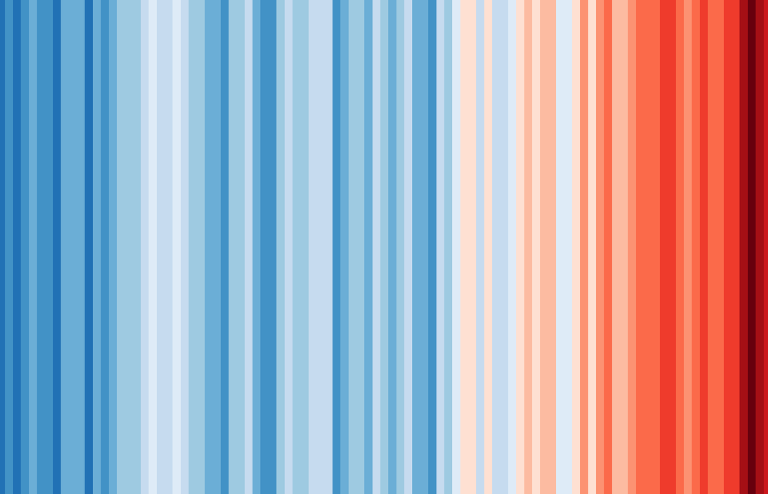

Teaser photo credit: Ed Hawkins‘ warming stripes graphics portray global warming since 1850 as a series of color-coded stripes, purposely devoid of scientific notation to be quickly understandable by non-scientists.[1] Blue (= cool) progresses over time to red (= warm). By Ed Hawkins, climate scientist at University of Reading – Hawkins, Ed, 2018 visualisation update / Warming stripes for 1850-2018 using the WMO annual global temperature dataset.. Climate Lab Book (4 December 2018). Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. "LICENSE / Creative Commons License / These blog pages & images are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License." (Direct link to image)., CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=80976980