Two high-profile events relevant to this series are going to coincide next month. One of them—the U.S. midterm elections, which will conclude November 8—could provide the strongest indicator yet of which way our society will turn in the near future: toward an inclusive, pluralistic democracy or toward the anti-democratic “semi-City Lifascism” of the MAGA right. It could go either way. In contrast, the other big event—the COP27 global climate conference November 6 to 18—is highly unlikely to bring any perceptible change in the trajectory of world greenhouse-gas emissions or anything else.

Indeed, the election results could have more profound consequences for the Earth’s climate than the climate conference will have. If, in November of 2022 and 2024, pro-democracy candidates prevail at the polls and the will of the voters is not overturned, passage of bold new climate legislation won’t be guaranteed, but the possibility will at least remain alive. If, however, by hook or by crook, MAGA politicians prevail in large enough numbers to seize control of both houses of Congress and the White House, any chance for effective national climate action will be lost for years to come. In either event, expansion of local struggles for climate action and environmental justice will be needed more than ever, as a foundation for a bigger, stronger national movement. This month, I spoke with two climate activists who are working tirelessly toward those goals.

Taking Down the Fossil Gas Lines

Liz Karosick is a visual artist and climate activist with Extinction Rebellion in Washington, D.C. (XRDC). Karosick says that while protecting and extending the right to vote is important, it’s not sufficient: “The system’s not working. If voting was enough, the will of the people who go into the voting booths would be represented here in Washington, and it’s not.” That makes it even more important, she says, for more people to take part in grassroots movements, in order to “build those numbers before things progress even further into the scary future that we’re looking at.”

That kind of organizing is, by its very nature, local. And what better place to energize national climate mitigation through local environmental-justice organizing than in the nation’s capital? That’s why, says Karosick, XRDC has kicked off a campaign against Washington Gas Light Company, the city’s sole supplier of fossil gas. Traditionally known by the euphemism “natural gas,” fossil gas consists mostly of methane, a compound with powerful global warming potential.

Washington Gas has some of the oldest distribution lines in the nation, and a 2014 survey found more than 6,000 leaks in the system—about four leaks per mile of pipe, largely in the city’s low-income and Black neighborhoods. Some of the leaks posed a serious explosion risk. The company responded by launching a 40-year, $5 billion program to replace the entire pipe system.

Because installation of new gas infrastructure would throw the city’s climate-mitigation goals completely out of reach, XRDC is demanding that the D.C. Council stop the pipe replacement project (except for emergency repairs of hazardous leaks) and immediately launch a just transition away from gas that prioritizes D.C.’s most marginalized people and ends the city’s dependence on gas.

Fossil gas is a threat to humanity and the Earth at both the largest and smallest scales. A federation of state-based, citizen-funded public interest research groups, PIRG, reports that gas leaks across the U.S. from 2010 through 2021 led to the release of 26.6 billion cubic feet of methane, with a global-warming impact equivalent to more than 2.4 million internal-combustion vehicles driven for a year. Meanwhile, open gas flames from stoves, furnaces, and water heaters also produce large quantities of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and other indoor air pollutants. These gases can cause severe respiratory problems—affecting children, especially—and are found disproportionately in low-income and Black communities.

An XRDC press release has more on the campaign to pressure the D.C. city council to phase out gas as quickly as possible.

Karosick stresses that what she calls “hyper-local” actions such as the D.C. fossil gas campaign are necessary building blocks of global climate action:

“I get a sense that some people are confused, like, “Hey, fossil fuels are a global problem, much bigger than a local gas campaign. Why this issue?” But strategically, we’re mobilizing with an issue that’s local, that will build momentum behind local demands—like telling Washington Gas, “No, you cannot spend $5 billion on new pipes to lock us into 40 more years of burning fossil gas.” This is a way to change the trajectory, electrify the city. We feel like this is winnable. And then we can go back to expanding upon broader demands. We’re finding leverage points where we can access the people who have decision-making power and move public opinion.”

Taking on Tesla

The way that young people have been taking the lead on climate in recent years has been especially heartening to Karosick, who says the climate movement is hoping for a massive influx of members in years to come. “The more young people who participate, the more change we can make,” she says. “It’s not a matter of explaining to them what the problem is—they’re very aware of that.” Still, groups like Extinction Rebellion can offer solidarity and additional opportunities for mobilizing. And, she says, “in our case, that includes nonviolent civil disobedience as the mechanism to get the government to pay attention and to make change.”

As it happens, I also had the opportunity recently to interview Alexia Leclercq, 22, a climate and environmental justice activist and a co-founder of the nonprofit Start:Empowerment. Our conversation took place onstage at The Land Institute’s annual Prairie Festival. (See the video here. Leclercq’s and my conversation runs from about the 14-minute to the 59-minute mark.)

In 2019, Leclercq began working with the environmental justice group PODER (People Organized in Defense of Earth and Her Resources) in Austin, Texas. Formed in 1991, PODER has an impressive track record, as she explained:

“Austin is highly segregated due to redlining. East Austin is a largely Black and Brown community, zoned industrial. A bunch of community members came together and started organizing to fight the dirty industries there. They started petitioning door to door, talking to the media, hosting toxic tours for politicians so they could see the conditions that community members are living in. PODER was incredibly successful. They kicked six major oil companies out of East Austin.”

At the time Leclercq began working with PODER, East Austin was still being plagued by a host of problems, including pollution from gravel-mining operations and lack of access to clean and affordable water. And then there’s Elon Musk’s electric vehicle company, Tesla. According to Leclercq,

“Tesla came in with zero plans for community engagement. We built out a coalition and started talking to the press to the point where they had to answer our emails and come talk to us. You could really tell from their company culture, that this wasn’t something that they necessarily cared about. They saw East Austin community members as a workforce to exploit, just as they were exploiting the land, air, and water. Loose regulations in Texas are one of the main reasons they’re there.”

Leclercq told the audience,

“We’re trying to push Tesla to make commitments, such as ecological restoration, community education programs, hiring Spanish speakers, and having programs for Spanish speakers to learn some English.” But in dealing with any corporation, she said, “it’s always kind of like a back-and-forth dance: How much do you really want to collaborate with them? How much external pressure do you apply? It’s a fine line.”

Taking a Stand Against Manchin’s Side Deal

“I work outside of the system, trying to build community and resilience and mutual aid, and I also do work that’s more like inside the system, both local and federal,” said Leclercq. At the time we spoke, her “inside” efforts were focused on a measure then before the U.S. Senate to speed up the permitting of energy projects. The legislation would theoretically streamline all energy sources; however, its primary sponsor, Democratic senator Joe Manchin, valued it most dearly as a vehicle for expediting construction of the Mountain Valley Pipeline to carry fossil gas out of West Virginia, the state he represents. In August, he had insisted that this side deal for fast-tracking his pet pipeline be included in future legislation as the price of his vote for the ostensibly pro-climate Inflation Reduction Act.

Leclercq joined a group of fellow activists in signing an open letter opposing the Manchin side deal. At last count, the letter had been signed by more than 600 grassroots groups and individuals as well as seven U.S. senators and 70 House members. “We’ve been doing a lot of lobbying, a lot of phone calls, a lot of press as well,” she said. A few days after we spoke, she headed to DC with the Environment Justice Leadership Forum—a coalition of around fifty grassroots BIPOC-led environmental-justice organizations—to turn up the heat on Congress. And they won! Faced with fierce opposition from grassroots groups and anti-gas congressional Democrats (as well as many Republicans who, while favoring quicker permitting of pipelines, were furious at the often-inscrutable senator for voting yes on the IRA), Manchin withdrew his permitting measure from the Senate’s year-end funding bill.

Next month, Leclercq will travel to Sharm-al-Sheikh, Egypt for COP27. As with all past COPs, she says,

“Most of us in the grassroots groups don’t expect radical change to come out of it, because of who’s leading it and because the Paris climate agreement doesn’t have any teeth anyway. We can’t have a top-down revolution—it has to be bottom up. We’re attending COP-27 just to make sure that our voices are there, and we’re not being completely screwed over at the same time we’re building movements at home to create the change that needs to happen. And in trying to build those movements, we have to ask, “How can we create alternative systems that are not colonial, that are not capitalist?” And, of course, we need more people on board.”

“It’s Not Something to Be Glamorized”

Responding to a festival audience member—a climate activist who had observed firsthand what she called the “over-exploitation of the energy, passion, and labor of young people involved in this work, which can sometimes lead to burnout”—Leclercq was blunt:

“I think every youth activist I know is burnt out, which is a problem. In organizing, there’s very much a culture of having to do more and more and more at the expense of ourselves, and we need to shift away from that. We need both self-care and collective care, because we’re looking to build a sustainable movement, and it doesn’t work to have people burn out and leave. We need to make sure that when we’re opposing systems like capitalism, we don’t perpetuate them in our own work. Making sure we have time off, we’re respecting boundaries, we’re distributing work fairly. The media like to kind of glamorize the youth movement, but it’s not something to be glamorized. I’m honored to be doing the work that I do, and so are all the incredible youth that I’ve met. But I don’t think that kids, especially young kids, should be responsible for doing all the hard work. I think it’s really important for us to encourage intergenerational organizing, and making sure that everyone of all ages gets involved and does their part to create a more sustainable movement.”

A few years ago, Leclercq and her friend Kier Blake set out to help build that more sustainable movement by co-founding Start:Empowerment, which describes itself as “a BIPOC-led social and environmental justice education nonprofit working with youth, educators, activists, and community members.” Rather than emulate mainstream environmental education programs by focusing on the physical and biological sciences, Leclercq said, she and Blake wanted to emphasize “the political component, the justice component. These are things that are not usually taught in schools. Youth spend most of their time in those schools, for thirteen years, K through 12. That’s a long time to not be learning about the climate crisis, about environmental justice, about organizing, about politics.”

Those gaps in learning, she said, “are a huge barrier to taking any kind of action. Before we can make any progress on climate and justice, there has to be mass education, and not necessarily in formal spaces.” The program is not just conveying knowledge, Leclerqc stressed; rather,

“we’re building knowledge together. It was really cool to see students connect their lived experience with some of the ideas we were introducing to them, and have them share what their perspective is from growing up in their neighborhoods, and how they saw environmental justice and injustice play out.”

* * *

In the peril-filled decade ahead, local, collective struggles by people of all ages—as exemplified by Extinction Rebellion, PODER, and Start:Empowerment—will be essential to advancing multiracial, pluralistic democracy and climate justice nationwide. Democracy and justice are prerequisites for ending our transgression of ecological boundaries and ensuring a livable future for all.

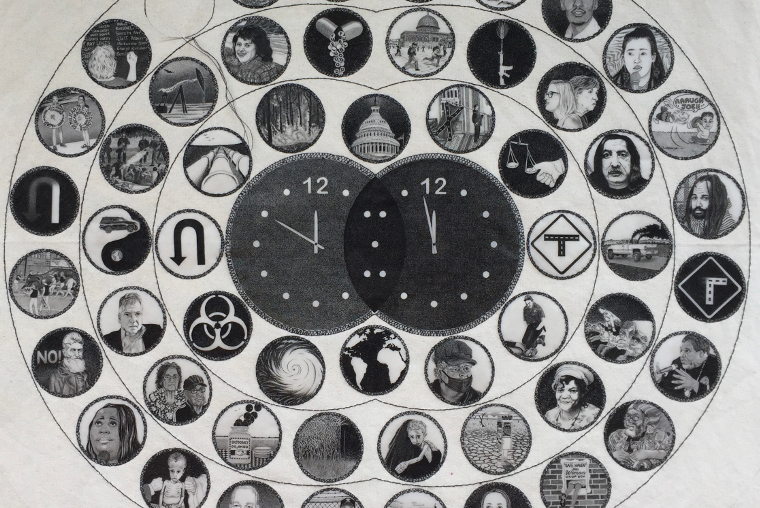

Artwork by Priti Gulati Cox