Ed. note: This article first appeared on ARC2020.eu. ARC2020 is a platform for agri-food and rural actors working towards better food, farming, and rural policies for Europe.

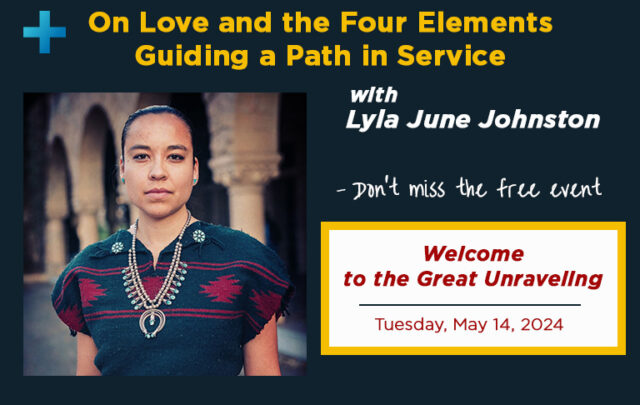

An alternative to the dominant agri-food system approach, ‘EcoSol-agroecology’ denotes a convergence of solidarity economy and agroecology movements. In Latin America, agroecology has been linked to the solidarity economy since the 1990s. Based at the Open University, UK, Les Levidow coordinated the AgroEcos project, which promoted and facilitated Eco-Sol agroecology networks. Here Levidow shares key learnings from Brazilian case studies. He introduces us to initiatives in the Baixada Santista region of São Paulo state, including a women’s producers’ union that reorganised their farmers market during pandemic restrictions first as an online fair and then as a drive-thru so members without internet access would not be excluded.

The dominant agri-food system prioritises wealth extraction through global value chains, rather than people’s food needs. Food insecurity and malnutrition are worsening globally, alongside many environmental harms, thus aggravating inequalities.

As one driver of these deteriorations, state policies continue to prioritise the production of commodity crops including maize, wheat and rice. A positive impact of this approach is the increased availability and reduced prices of these staple foods in many countries. However, this policy priority discourages and makes relatively more expensive the consumption of less subsidised foods such as fruits, vegetables and pulses, according to the FAO, and can perpetuate food insecurity and malnutrition.

More fundamentally, the problem lies in the corporate concentration of the food system, which mainly benefits input-suppliers and middlemen to the detriment of producers and consumers.

Agroecology as an alternative to the dominant agri-food system

A food system solution lies in a comprehensive agroecology agenda. This should ‘ensure proximity and confidence between producers and consumers through promotion of fair and short distribution networks and by re-embedding food systems into local economies’, especially through a solidarity economy, says the FAO’s High-Level Panel of Experts.

Amid calls to seek solutions beyond capitalism, the social and solidarity economy (SSE) offers a practical way forward. ‘At the very least, you get practice in how to do things differently; more optimistically, you build an alternative, fairer and more interconnected economy’, argues ARC2020. Peasant agroecology as championed by European Coordination Via Campesina, empowers local, circular markets building autonomy from global corporate markets.

Learning from Latin American Strategies

In the European context, ‘agroecology has embraced a social and solidarity economy (SSE) approach in agriculture, but it is still in its infancy and will need political vision and consumers’ engagement’, says Agroecology Europe. In Latin America, Agroecology has been linked with the solidarity economy (economia solidaria) since the 1990s. European efforts can learn from their strategies.

EcoSol-agroecology: building circuitos cortos

The AgroEcos project promoted and facilitated networks that merge agroecology and the solidarity economy

In Latin America ‘EcoSol-agroecology’ denotes a convergence of social movements for economia solidaria and agroecology. This was the focus of our AgroEcos project, ‘Research Partnership for an Agroecology-based Solidarity Economy in Bolívia and Brazil’, which analysed and facilitated EcoSol-agroecology networks through Participatory Action Research with them.

The project focused on short food-supply chains, known there as circuitos cortos. The research investigated these central questions: How did those networks build collective capacities for circuitos cortos? How did they extend such capacities to overcome many obstacles during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Societal proximities

As a general answer: circuitos cortos depend on common solidaristic purposes, which activate and link societal proximities of various kinds (organisational, cultural, institutional, geographical). These proximities in turn depend on collective capacities which were extended to devise creative adaptations during the pandemic.

Although Latin America’s EcoSol-agroecology networks advocate food sovereignty, they rarely have succeeded in gaining its adoption by governments. As a different strategy, Brazil’s networks have intervened in government policy on food and nutritional security so that it incorporates some features of food sovereignty, especially solidaristic forms of agroecology. The networks have also promoted women’s leadership (protagonismo femenino) as central.

Baixada Santista: solidarity network

These general strategies are illustrated here by a case-study area, the Baixada Santista, which has relevance to European contexts. Named after the major port city Santos, the Baixada Santista has nine small coastal towns. Their food supplies depend mainly on imports from outside the region, especially through wholesalers and supermarkets selling ultra-processed food.

The population has great socio-economic inequalities, featuring food poverty and food deserts in peripheral areas. Some peri-urban areas have a potential to start or increase agroecological production, yet they lack means of directly reaching consumers. Moreover, this potential is being undermined by heavy forms of coastal tourism.

There the AgroEcos project has a communitarian partner: the Fórum de Economia Solidária da Baixada Santista (FESBS). It links various artisanal initiatives, especially EcoSol-agroecology networks. Its Manifesto advocates various support measures to build ‘an economy of proximity’ that could overcome inequalities in employment, income and food security. The Manifesto proposes a solidarity transition. In this perspective, artisanal producers (and service providers) organise themselves to practice solidarity financing, market products, buy inputs collectively, strengthen food security and share knowledge. The Forum encompasses numerous towns and initiatives.

Peruíbe: Solidarity Network and Women’s Union

‘Constructing a new reality’ – the slogan of the Peruíbe Solidarity Network

Before the pandemic the Peruíbe Solidarity Network was organised as a means to unite people who produce artisanal products (including agroecological food), fishers and service providers. This network has sought to commercialise locally and promote reciprocity among its members. Its activities strengthen an organisational proximity among producers. During the pandemic an online fair and Facebook page were created to promote all available artisanal products, especially food. The network spread the slogan ‘Constructing a new reality’, signifying alternatives to dominant global markets and thus strengthening a cultural proximity with consumers.

The Women’s EcoSol Producers’ Union (UMPES) was created in 1987. It has co-organised a farmers’ market, supported by the Rede Solidária and the municipality. Its common purposes emphasised reciprocity, mutual aid and self-management, as well as means to deal with gender inequalities. ‘When a woman requests any kind of help, we offer a hand as a form of solidarity.’ Training courses helped some women to establish a Social Control Organization (OCS) for collectively certifying their products as organic. Some groups sold organic products collectively for school meals through the government programme; thus they constructed an institutional proximity with the local authority.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, UMPES helped many vulnerable families and facilitated exchanges. Members bartered surplus products in order to offer consumers more variety and increase their income. This new practice played a role of solidarity: ‘We value product exchanges, seen as a necessary practice to create fairer relationships.’

The farmers’ market was temporarily replaced by an online fair through social media. The physical market was re-organised as a drive-thru with a collective stall. This had importance especially because few UMPES members have internet access for online orders. As another reason: ‘It is necessary to speak with consumers to facilitate an understanding of EcoSol. A physical space is very important.’ Such products include artisanal bread with natural fermentation, as well as lightly processed products with spices, evoking memories of childhood foods. By such means, UMPES maintained or constructed a cultural proximity with consumers.

The Women’s EcoSol Producers’ Union drive-thru market stall. Photo: Juanita Trigo Nasser

Santos: la Livres Coop

Livres Cooperativa, Santos. Photo: La Folha Santista.

In Santos, la Livres Cooperativa Consumidores Conscientes exemplifies Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA by conscientious consumers). Its name Livres (‘free’) has two meanings: products without agrochemicals, and circuitos cortos without capitalist middlemen. ‘We promote or popularise access to produtos do bem’. This evokes the cosmovision of Bem Viver (Buen Vivir in Spanish).

La Livres organises weekly baskets for its member-subscribers. The subscriptions connect production and consumption under the principles of solidarity economy. La Livres supports farmers in rural locations far from the city and disseminates news about their agroecological methods to consumers. It promotes seasonal foods and recipes to cook them, as a means to counter the dominant global food chains in supermarket chains. In all these ways, it builds a cultural proximity between producers and consumers.

During the pandemic, la Livres offered the option of picking up the food basket directly from the venue or receiving a basket at home – delivered by ecobikers from a solidarity-based cooperative. The Livres Coop then received many more orders, soon exceeding the food supplies. It highlights mutual aid and voluntary work, for example, to help assemble the weekly baskets.

Project results available

As these examples illustrate, our analytical framework of societal proximities helps to identify and facilitate solidaristic circuitos cortos. These are crucial for agroecological production to provide its many benefits, including food and nutritional security, alongside countering the hegemonic agri-food system.

The AgroEcos final report explains that framework, which has general relevance to any context. It is available in English and Spanish. The webpage also has more detailed reports in Spanish or Portuguese.

Two case studies have films with English-language subtitles: “Baixada Santista, Brasil: redes solidarias agroecológicos” and “Agroecologia, Pesca e Economia Solidária na Bocaina em tempos de Covid-19”

Further reading on the Baixada Santista case study can be found in long-form articles published by Agroecology Europe and the Journal of Peasant Studies.

Teaser photo credit: Activists of the Peruibe Women’s Solidarity Economy Producers’ Union (UMPES) in the Baixada Santista region, Brazil. Their logo can be seen in the background. Photo: UMPES, Peruibe