I recently watched a Netflix documentary series about fundamentalist Mormons, exposing along the way a number of beliefs that seem bizarre from the outside, but that are accepted as perfectly normal within their insular community. Though the term “cult” is not used in the series, it is hard not to see the sect in this light. It would be nearly impossible to convince any one of its members that they are deeply in error, in part because doing so threatens the salvation that has been dangled in front of them. If they are pure enough in their faith, resisting external evils that try to knock them off the one true course, eternity is theirs. In today’s world, one need not look far to find other groups whose beliefs are at once bonkers and seemingly immune to attack.

Hearing the perspectives of ex-members of these cults never fails to be fascinating, providing a window into how they could have swallowed all the lies and goofy stories. Also important to know: it is possible to escape, and to suddenly see the magnitude of the deception. Once out, there’s no going back.

Cult beliefs look insane from the outside, so why don’t its adherents detect the lunacy? Why is it so hard to convince them of their folly? One possible answer—as a tangent—is that cults offer a deeply satisfying sense of identity, belonging, and (seemingly) unconditional acceptance/support within its community that we have otherwise lost in today’s society, but that in times past were central offerings of tribal life to which humans are intimately adapted. It is remarkable how quickly tribal cohesion instincts of mutual help resurface as soon as core elements of civilization (provision of food, water, electricity, for instance) fail in a natural disaster. We’ve still got it, underneath the veneer.

Leaving that for another time, let me now condemn myself in the court of civil opinion by making the charge that most people on Earth are members of a dangerous cult whose central beliefs seem every bit as bizarre to one who has escaped the thought prison, but that are seldom questioned and even fiercely defended. This post offers ten heretical statements that seem obvious to me, but tend to produce emotionally charged reactions by members of the cult of civilization. Watch yourself, now.

Let’s start by just unloading them all, in compact form, each point to be briefly unpacked in what follows. Some of the points essentially follow from previous ones, but are powerful (jarring) enough to deserve their own statement.

- Humans are not the reason for all of creation: not the end point or goal in this universe.

- A human life is no more sacred than that of a wolf (as just one example).

- Our civilization is not any sort of destiny: not the only or best way to organize ourselves on this planet.

- We are not building civilization—brick by brick—according to some master plan aiming toward a “better” end: no paradise/salvation awaits on the current path.

- Technology and innovation are slowing, not accelerating.

- Technology (ahem; renewable energy) will not solve our big problems.

- Space colonization is an infantile fantasy that is not part of our future.

- Growth is destined to end: we have hitched ourselves to a losing wagon.

- Monetary valuations badly miss the mark by orders-of-magnitude, so that decisions based on money (i.e., most societal decisions) will be bad ones.

- Malthus was wrong only in his optimism that population will saturate and stabilize.

I don’t expect many to make it through the list without at least a “wait a minute…”

Okay, readers of this blog are perhaps more predisposed to this way of thinking, but that’s a skewed representation of “normal” people—many of whom may find themselves to be offended or even apoplectic. To me, that sort of reaction betrays a bit of…cultishness. Perhaps the best way to explain is for me to state as succinctly as I can why each of the statements seems like obvious dispassionate truth once free of the baggage.

1. Humans are not All That

Humans are not the reason for all of creation: not the end point or goal in this universe. After several billion years of evolution, why would a genus that arose on one of the many branches only 3 million years ago (and our species a tenth of that duration) possibly be an end point? Why would evolution come screeching to a halt now that it has “achieved” homo sapiens? Presumably, a few billion years of evolution lie ahead, and many new ideas will be explored—the vast majority having no lineage from homo sapiens. Evolution tries many strategies for success (and even more leading to failure). Intelligence is just one of those, and not necessarily an optimal one. So it is not at all guaranteed that homo sapiens will have descendants left on the stage millions of years hence. We should get over ourselves. Moreover, Earth is one planet around one star among many billions in our galaxy—itself one of many billions of galaxies. Of course we’re not the raison d’ê·tre for the universe, if you’ll pardon my French.

2. Not Sacred

A human life is no more sacred than that of a wolf (as just one example). In some sense, neither are sacred. This partly flows from the previous point. If humans are not the apex—the whole point of the Earth, Galaxy, or Universe being here—then why is one life within a robust population that important? When an ant colony inevitably experiences a factor-of-ten seasonal reduction in population, it’s no tragedy: they’ll bounce back next spring. When flamingo chicks die by the hundreds in their perilous migration from the drying flats, it’s part of the time-tested cycle. What’s important is the propagation of the species, and the maintenance of biodiversity. The fate of individuals has little grand meaning. Once humans are seen as just one of millions of animal species on the planet, it becomes hard to argue that the life of a (comparatively rare) bear who kills a human is any less valuable than that of the human now eliminated from among 8 billion. Human rights represent a self-promoting construct we just made up for our exclusive benefit. This point is likely to raise some readers’ hackles. Don’t read in more than dispassionate logic: strong objections are the cult talking.

3. Civilization is not All That

Our civilization is not any sort of destiny: not the only or best way to organize ourselves on this planet. Tangled with the sense of human exceptionalism (point 1) is the notion that the civilization we have raised over the last 10,000 years out of the dust bin of prehistory is an expression of destiny. If humans are somehow the ultimate species—the focal point of evolution—then whatever we end up doing is also meant to be. What we have done is so extraordinary in the entire history of the planet (no argument from me here) that it must have some grand meaning and be the right path. But what if it is extraordinarily wrong or a colossal mistake? Humans lived a different way for 3 million years, and that way happened to work long-term (by construction). The current way is untested over relevant time scales, and is so obviously unsustainable at today’s scale that it was most likely a wrong turn. I’m not saying that primitive tribal life is the only solution either: just that today’s civilization isn’t the answer, and perhaps we should contemplate ditching it for something entirely different (built on a foundation of truly sustainable principles, living as subordinate partners to all other life on the planet).

4. No Paradise

We are not building civilization—brick by brick—according to some master plan aiming toward a “better” end: no paradise/salvation awaits on the current path. How could we be building toward perfection when no one has a fully formed architectural design that we know will work? No: we’re just throwing down bricks and mortar in some slapdash fashion and assuming it is going somewhere good. The key problem is that our unexamined foundation won’t support many more bricks, and we run a great risk by blithely slapping more down just because it’s been fun so far. It’s time we stop just doing things because we can in the moment, and ask what long-term sustainability might even mean.

5. Technological Slowdown

Technology and innovation are slowing, not accelerating. The pace of innovation exploded alongside the introduction of fossil fuels and the energy it unleashed. I like to play a mental game of transporting someone from 1900 to 1960 while doing the same for an inhabitant of 1960 popped into 2020. Which is more mystified by “magic” all around? 1960 technology is bewildering to the 1900 resident (surrounded by new things without names, even), while 2020 shows mostly snazzy refinements but few unrecognizable elements of everyday life. As important as energy is to the functioning of our civilization, and as clear as it has been since the 1970s that fossil fuels would not provide indefinite energy, no fundamentally new energy technologies are on the table that were not also around in the 1970s. Sure, they’ve become more efficient in many cases, but are now approaching theoretical maximum efficiency. No transformational revolutions are imminent.

6. Technology Will Not Save Us

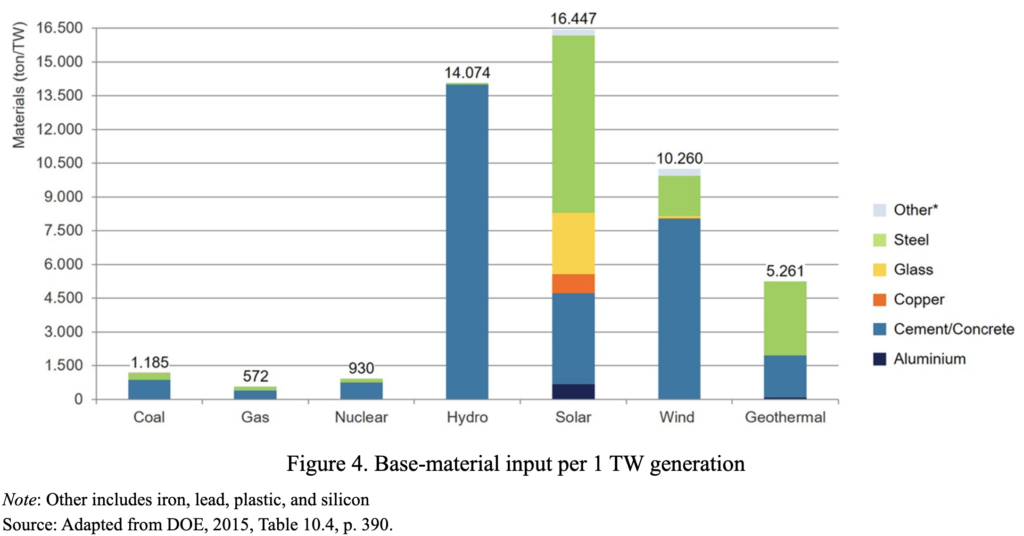

Technology (ahem; renewable energy) will not solve our big problems. Faith in technology is actually pretty scary to me. I’m a technologist. I’ve had a career exploiting cutting-edge capabilities and inventing things that work. As such, I feel like I’m in a better position than most to know what it can and can’t do. It won’t defy physics, for one thing. It’s not an unlimited bag of magic beans. It is easy enough to see where the faith comes from (just look in the rear view mirror). But this facile thinking lacks specificity. I have written about how a complete replacement of fossil fuels by renewable technology could actually be a nightmare for the ecological health of our planet. To emphasize this, the following graphic shows the potentially devastating resource impact that renewable technologies could have on the planet. We would shift the current war on the atmosphere (CO2) into a relentless assault on the land that would never cease since components continuously need replacement as the future grinds on. Our planet cannot likely afford to host our technological ambitions for much longer.

The “good” energy sources are hella taxing on material resources. From https://ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/jms/article/view/0/47241.

7. Space Fantasy

Space colonization is an infantile fantasy that is not part of our future. Provocative wording, for sure, but to me reminiscent of the Mormon idea that the especially devout would inherit their own planet in the afterlife. If you subscribe to the space-faring hope, ask yourself how deeply you understand the challenges: the scale, energetic requirements, the paucity of resources important to sustaining life, the indifferent hostility and isolated unsurvivability of non-earth environments. Mount Everest and the ocean floor are orders-of-magnitude more habitable than any non-terrestrial setting in the solar system: much easier to access and nearer to restaurants. Yet we do not see condominiums in those locations, do we? Nor do we expect to—because it’s obviously silly, just like space colonization. A recent analysis I participated in suggests that one of the fastest ways to destroy Earth would be to consume the unfathomably large amount of resources that leaving the planet would require. So if you are attracted to the notion that leaving the planet is the best way to save it from ourselves, think again!

8. Limits to Growth

Growth is destined to end: we have hitched ourselves to a losing wagon. This one should be easy: exponentials don’t survive long-term in finite settings. Do the Math began on this concept, and I still find the need to make the point. It’s surprisingly controversial, so something very strange is going on in the cultural teachings. Since so many of our institutions are designed around the expectation of growth, our faith in its continuance puts us in danger. Also, it’s this growth train that creates the many hockey stick curves, which spells doom for ecosystems even without any consideration of CO2.

9. Money Sucks

Monetary valuations badly miss the mark by orders-of-magnitude, so that decisions based on money (i.e., most societal decisions) will be bad ones. Two ways to demonstrate this: 1) Estimate the monetary value of a planet—even without considering the billion-plus-year investment evolution has made in forming a complex biopshere—and we learn that the annual global monetary scale is about six orders-of-magnitude smaller than the value of a barren planet. 2) Animals are worth more than their weight in gold, which suggests that a chicken is worth $60,000, not $5. Both approaches are flawed, but at least hint at how grotesquely distorted our financial approach to everything is. We place essentially no value on stuff that is priceless and that we could not live without. How is that a good idea? Because we base most big decisions on financial considerations, we grossly neglect the important things, and will continue to make devastatingly bad decisions for the long term by continuing this deeply immoral practice.

10. Malthus: That Optimist!

Malthus was wrong only in his optimism that population will saturate and stabilize. Thomas Malthus worried that finite land (from which all energy derived via captured sunlight prior to the exploitation of fossil fuels) would translate to a cessation of population growth once saturated. His prediction of when that would happen missed the mark by perhaps a few centuries due to the unforeseen arrival of fossil fuels onto the scene. Economists use “Malthusian” as a derogatory synonym for “wrong,” and bludgeon any similar-sounding suggestion about future limits by employing an expression of (blind) faith that something else as transformational as fossil fuels will surely always come along in time to obviate the concern. The ironic problem here is that the reason Malthus was “wrong” (fossil fuels) will also make him wrong about saturating population at some presumably steady-state peak. The connection is overshoot. What did we do with our fossil fuel bonanza? We exploded population by revolutionizing agriculture. Now when fossil fuels inevitably (and soon?) decline, we’re left with an overhang that can no longer be supported. The resulting population decline will suddenly cast Malthus in a new light: oh what a starry-eyed soothe-sayer! When that day comes, take a lesson from point #2 and realize that it’s no more tragic than the ant colony waning as it must.

Escape the Cult?

If you can see at least glimmers that our civilization has placed us in a precarious predicament and filled our heads with dubious axioms, then I am heartened. This is where I see hope: that we can slough off this cult(ure) and adopt a new start that respects things of real lasting value. Walk away. Where will you go? It’s scary to leave a cult: most don’t or can’t. I haven’t completely left either: I’m just aware that we need to. I may never be free from it as an individual, and neither might you be. But we might recognize our big mistake and prepare future generations in a way that does not fill their heads with damaging notions. Like the dying Darth Vader, it may be too late for us. But perhaps we can help destroy the belief system that would otherwise bind us and countless other species to an unfortunate fate.

Teaser photo credit: From Pixabay/KELLEPICS