Ed. note: This piece is part 3 of the Eating Ethically and Affordably in Vancouver series originally from the Tyee, and is reposted here with permission. Part 1 of this series can be found on Resilience.org here, and Part 3 can be found here.

Locarno Beach is packed with families firing up BBQs, flying kites and handing out watermelon slices. Children shriek and chase after one another while parents flop into camping chairs in the shade.

I’m here for a foraging class about what I can harvest off the beach. I want to know if I can fill my grocery bags with what we find on the tidal flats at Locarno.

When the tide goes out, is the table really set?

In part one of this series I explored urban farms, community gardens and new and innovative ways to connect with small-scale farmers in the Lower Mainland.

In part two, published last week, I volunteered with the Vancouver Fruit Tree Project and chewed through the thought experiment of transforming the urban tree canopy into a sprawling public orchard.

This week I’m looking at foraging local plants and animals. Vancouver is a coastal city with beaches littered with Pacific mussels and varnish clams, and lush parks overrun with rabbits and Canada geese. All of these things are edible — so why aren’t they also considered valuable urban food resources?

I grew up on beaches around B.C.: crushing mussels on Bowen Island docks and dropping their pulped bodies into the water to attract shiner perch; walking hundreds of metres across the Centennial Beach mudflats to reach its tepid waters; turning over rocks at Hornby Island’s Helliwell Provincial Park to peer at the strange, alien life huddled there.

But I’ve never eaten off the beach.

Truth be told, I’m afraid to. I’ve seen the skull and cross-bones signs posted on beaches my whole life. Isn’t it dangerous to eat from polluted local waters?

I signed up for a Swallow Tail Canada sea foraging class to help fill in some of my knowledge gaps.

A lot of things are edible in the ocean but it’s important to know when, where and how much you can harvest, says Robin Kort, the chef behind Swallow Tail adventures.

A naturally occurring poison known as paralytic shellfish poisoning, or ‘red tide,’ can build up in filter feeders, like clams or muscles, and kill you within 12 hours if eaten. If you see an area is closed for shellfish harvest it’s best not to risk it. Photo by Michelle Gamage.

Shellfish are filter feeders and can accumulate a naturally occurring, tasteless, odourless and colourless poison called paralytic shellfish poisoning, which is also known colloquially as “red tide.”

One of the most potent natural poisons in the world, paralytic shellfish poisoning can kill you within 12 hours, according to the Government of Canada. There is no known antidote.

Seaweed can pick up heavy metals and crab liver shouldn’t be eaten if you harvest the crab from potentially polluted waters, Kort says.

That’s the bad news.

Here’s the good news.

There are excellent Fisheries and Oceans Canada and BC Centre for Disease Control maps that tell you where you can and cannot harvest seafood.

The maps will always take a precautionary approach because the government is extremely risk-adverse, so if the map says an area is open for harvesting you know it’s safe, Kort says.

When harvesting from the ocean, it’s best to focus on abundant species, like male crabs, sea urchins and seaweed, she adds, and avoid less-abundant species like Olympia oysters or female crabs that might be better off left alone.

It’s also a good idea to harvest while the tide is going out or at the lowest possible tide to make sure the animals stay in the cold water for as long as possible, she says. (You can check local tide tables here. Tides change month to month, so certain times of the year are better for harvesting animals that hide in deep waters, Kort says. Most tides range from between zero to five metres — but some tides go below the “zero metre” mark. These are known as negative tides and are an excellent time to harvest geoducks, sea urchins and sea cucumbers.)

You also want to avoid harvesting anything close to a marina or a pier with creosote-treated logs.

To harvest just about anything from the ocean you need a licence. A tidal water sport fishing licence costs $22 per year.

That allows me to harvest, per day: four crab, 12 sea urchins and unlimited seaweed for about six cents a day on average.

Dungeness crab are one of the only food sources you can catch and eat off Vancouver’s beaches, Kort says. She’s brought a clamshell crab trap with her and we practise casting it into water off the sandy beach.

Chef Robin Kort casts a half-moon crab trap off Locarno Beach in Vancouver. You want to cast the net and pull it in at least once every 15 minutes, keeping the line taunt as you reel it in, she says. Photo by Michelle Gamage.

Turkey necks or bones with bits of meat attached are the best kind of bait for any crab trap because crabs are scavengers and will try to grab a chunk of food and run away, she says. One student hauls in crab as big as her palm, but we release it because a crab must be 16.5 centimetres wide to be harvested.

All female Dungeness and red rock crabs must immediately be released. A female crab will have a wide beehive-shaped abdomen and a male will have a narrow lighthouse-shaped abdomen. Crabs should be gently released into the water — throwing them back in can hurt them. Photo by Michelle Gamage.

Clamshell crab traps are great to take camping or hiking because they’re low-cost, lightweight and provide delicious protein, she says. You can also make your own trap in an afternoon — so long as it follows provincial guidelines.

Kort says the best way to eat crab is to kill it (humanely) and harvest its meat from the hard shell. Cook the meat in an inch of butter and white wine, covered, for 15 minutes.

Anywhere that’s open for shellfish harvest is also a good spot to pick seaweed, Kort says.

Almost all seaweed in B.C. is edible. Kort passes around fresh and smoked rockweed (it’s chewy and lightly salty, almost like kale drizzled with sea water), sea lettuce (it’s so delicate! It grows two-cells thick and feels like eating gently salted fruit skins) and sugar kelp (packs a big salty punch like a potato chip, good for adding to soup) that she harvested from Galiano Island.

Seaweed can be harvested from the beach because it’s still alive as it floats through the water, Kort says. The provincial government says you can harvest 100 kilograms of seaweed for personal use without a licence so long as you don’t hurt the plant. Don’t rinse your seaweed before eating it and eat within a day of harvest, Kort adds.

Can we eat BC’s abundant feral bunnies?

After her class, Kort’s students sit at a picnic table and tuck into a salmon chowder, flavoured with tomatoes and seaweed. My bowl features a large crab claw, which I greedily crack open to suck out the buttery meat.

I had no idea I could forage this kind of protein from the beach.

In an overly dramatic moment of realization, I slowly look up from my chowder and lock eyes with a Canada goose.

What other kind of local, wild protein could I be missing out on?

Unfortunately, it seems like Jericho’s bunnies and Canada geese are off limits — but no one was able to tell me why.

B.C’s Hunting and Trapping Regulations Synopsis says it’s up to municipalities to set their own bylaws around weapons, firearms and bows within municipal limits.

City staff in Vancouver and Victoria said harvesting urban wildlife was prohibited, but couldn’t provide clarification as to why.

A spokesperson for the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation said urban wildlife is managed by the province, but added traps and snares “cannot be positioned around the city, simply due to the risk it presents to people and animals that use public spaces.”

In an emailed statement the Ministry of Forests said hunting and trapping is heavily regulated and all trappers must complete a BC Trapper Education course, have a licence and only trap during a specific time. Traps are not allowed within 200 metres of a home (meaning most people can’t lure bunnies into a trap on their front lawns) and municipalities can prohibit the use of guns or bows, it added.

But even without feasting on roast Dude Chilling Park-caught goose, cities are full of edible plants.

Weeds aren’t real — but eat them anyway

A lot of plants get classified as weeds, but there’s actually no such thing as a weed, says Jennifer Grenz, assistant professor at the University of British Columbia faculty of forestry and faculty of land and food. So-called weeds are just a plant growing somewhere you don’t want it to.

Plus, plants that are classified as weeds are often edible.

Dandelions are important for early-season pollinators. Plus, all parts of the plant are edible and incredibly nutritious, she says. Himalayan blackberries are incredibly invasive but can thrive on underused, unwatered stretches along the side of a road or creeping along the wall of a back alley. Narrow leaf plantain is edible and can be used to make a salve for the skin.

For salads I’ve been picking dandelions, red and white clover and narrow leaf plantain from around the city — but a spokesperson for the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation cautions against picking low-lying plants from city parks.

Some Vancouver parks use fertilizers or a low-toxicity larvacide to combat an invasive Japanese beetle infestation — and these products are not food-safe, they say. “Parks are carefully maintained for public use but this isn’t done through the lens of creating a food-safe environment,” the spokesperson added.

So picking low-lying snacks is best done from private land (that you have permission to harvest from) so you know what the plant could have come in contact with. It’s also a good idea to wash the plants before you eat them!

The city also uses herbicides to control invasive species like knotweed and hogweed growth on public boulevards, the spokesperson says.

To control the growth of edible invasive species like blackberries, the city uses “mechanical measures, such as trimming,” the spokesperson adds. But if other invasive species were growing nearby there is a risk that some herbicide spray could land on the blackberries.

“Any use of herbicide is publicly posted from the time of application for at least a week afterwards and caution tape is installed around the treated areas,” they say.

Are we name-calling weeds?

The concept of what is and isn’t a weed, and what is and isn’t an invasive plant is rooted in xenophobia and colonialism, Grenz says.

“We’re taught we need to conserve and protect species as much as possible, without realizing it’s a colonial viewpoint to hit pause on the ecosystem,” she says.

Ecosystems are constantly in flux and Indigenous people have survived changes in speciation before, she says, adding that 5,000 years ago western red cedars may have been considered an invasive species as they dramatically spread out across the Pacific Northwest.

Even plants that are potentially harmful to humans have their pluses, Grenz says. Spotted knapweed is beneficial for pollinators. And all parts of poison hemlock are highly poisonous to humans, but the plant is native to B.C.

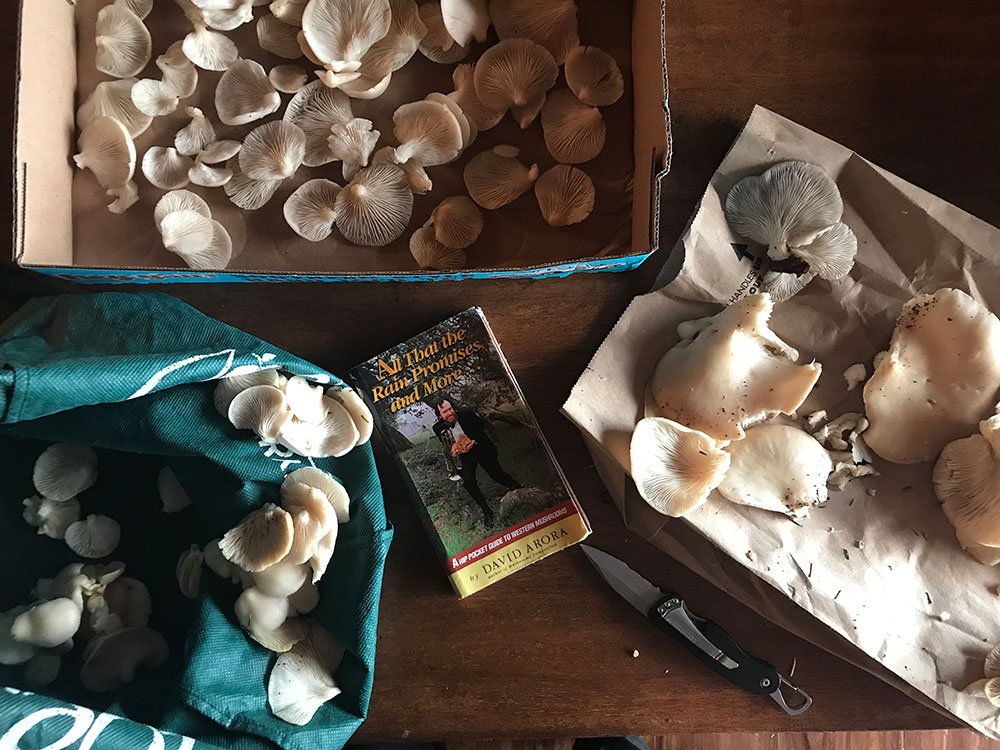

Mushrooms are another abundant food source you can harvest in and around Vancouver. These are oyster mushrooms I foraged an hour’s drive outside of the city. But we’re not including them in this Tyee series. Anyone interested in learning about foraging wild mushrooms should consider taking a class or reading some books first. Photo by Michelle Gamage.

It’s better to manage plants by breaking down their values, she says. Rather than classifying plants as invasive versus native, or weeds versus not, we should ask: could this plant harm human health, the environment or the economy?

Grenz is far from the only forager encouraging urbanites to reframe how they think about plants.

Alexis Nikole is an edible-plant enthusiast and cook from Columbus, Ohio, who creates short, educational videos about identifying, harvesting and cooking wild plants she finds in her own neighbourhood and surrounding forests on Instagram, for 1.1 million followers, under the username blackforager.

Ohio and B.C. have slightly different climates but Nikole has already introduced me to a handful of edible plants growing in my neighbourhood, like staghorn sumac, which can be used to make a lemon-free lemonade.

Nikole says staghorn sumac tastes like “free tree sour warheads.”

To make staghorn sumac-aide place one flower cone in cold water and steep overnight. Strain and add sugar to taste. Serve over ice for a refreshing, tart summer drink grown in your neighbourhood. Photo by Michelle Gamage.

To test this claim I wrangled my seven-year-old niece and we picked some staghorn sumac flowers from a tree growing in my neighbourhood.

“They’re edible, try them!” I tell her, popping some sticky flowers in my mouth to prove they’re not poisonous.

She sticks out her tongue and, slowly, with eyes squinted at me to check if it’s a joke, tries licking the flower.

There’s a pause, then her eyes light up. She pops a second peppercorn-sized flower in her mouth, then tries a handful.

“It’s so sour!” she cries, laughing with delight. Next she’s licking the tangy sour nectar off her hands and begging me to pick her more.

I’ve been told I’m no longer allowed to visit without bringing at least two “free tree sour warheads” with me.

Another urban forager is born.

So far with this series I’ve discovered a way to buy veggies from local, small-scale farmers. I’ve found a way to access locally grown fruit on private property around the city and have even found a way to harvest affordable daily protein off Vancouver’s beaches.

It feels like there’s an abundance of food — and there is. There’s actually more than we can reasonably eat, which will be the focus of next week’s article.

To wrap up the series we’re looking at the 13,000 tonnes of healthy, edible food that ends up in Metro Vancouver’s transfer station every year, and asking if we could eat better by changing what we consider waste.

Teaser photo credit: Chef Robin Kort demonstrates how to safely hold a Dungeness crab on Locarno Beach. Male Dungeness crabs over 16.5 centimetres wide can be harvested and eaten off the Vancouver beach. Photo by Michelle Gamage.