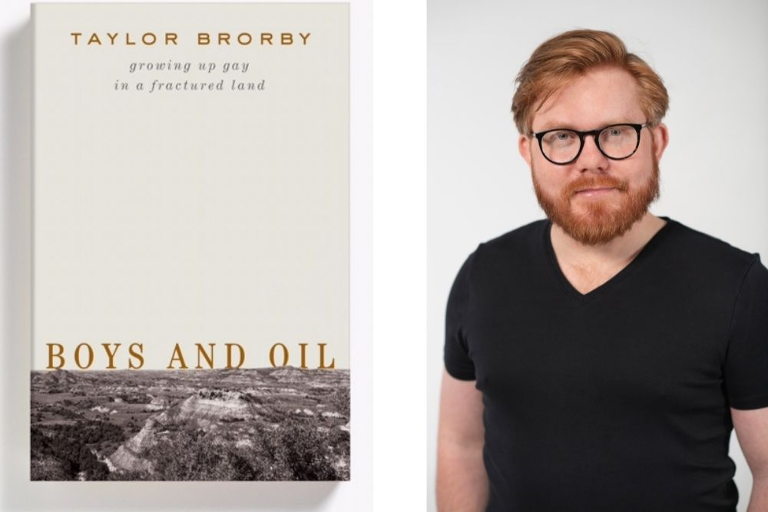

Boys and Oil: Growing Up Gay in a Fractured Land

Boys and Oil: Growing Up Gay in a Fractured Land

By Taylor Brorby

Liveright Publishing Corporation, Jun. 2022, 340 pp., hardcover: $27.95.

Also available in ebook formats.

Taylor Brorby’s memoir Boys and Oil is many things. It is a powerful coming-of-age story, a fascinating intellectual autobiography, a passionate paean to the natural wonders of Brorby’s native rural North Dakota and a stark warning about the ecological harms of fossil fuel extraction. Above all, it is a glorious tour de force of narrative nonfiction: a memoir that reads like the best kind of novel, with a gripping story and an astonishing sense of place, time and character.

Brorby is a poet, essayist and environmental activist who has written extensively on the damage caused by extractive industries like oil fracking and coal mining. This is more than a little ironic, given that he comes from three generations of coal workers—and the irony isn’t lost on him. But he fell in love at an early age with the bucolic prairie landscape on which he was raised in Center, North Dakota, reveling in its natural beauty and diverse ecosystem. It was this love of nature that eventually put him at odds with his family’s coal mining legacy.

Center is a tiny community, but Brorby says his world didn’t feel small to him when he was young. He recalls losing himself for hours at a time in his outdoor hobbies, which included fishing for bluegills, wandering creek banks in search of wildlife and taking in the prairie’s awe-inspiring sights. He captures these sights in sometimes literally painterly descriptions: “It is as if you are within the brushstrokes of a fiery painting,” he writes of the splendor of an autumn sunset.

Such idyllic descriptions are a momentary relief from the miasma of bitter despair that Brorby has come to perceive among Center’s human inhabitants. He calls the town’s overall aura one of “self-destruction” and “crushing weight.” He says the men of Center spend their days laboring at dangerous, backbreaking jobs in mines and boilers, and their nights anesthetizing their sorrows with alcohol. In a line that epitomizes Brorby’s talent for vivid, visceral prose, he writes that “each Monday, and every day after, the men stumble into the two bars, their sooted hands grip cold beer, warm whiskey.”

Brorby laments that he’s never been able to find a common bond with the people of his hometown—“I love the land, not the people,” he says. Growing up, he was bullied for being effeminate, and this bullying occurred not just at school but at home at the hands of his father, a man whose “loud gravelly voice always seemed tinged with anger.” With puberty came Brorby’s discovery that he was gay. Since his parents were deeply religious and no one at his school was out of the closet, he felt compelled to keep this part of his identity secret.

The isolation, unrequited attractions and feelings of otherness that plagued Brorby as a boy were almost too much for him to bear. What kept him going was the hope that there were others like him out there somewhere. He didn’t know for sure that there were, since it was only within the distant or fictional worlds of shows like Queer Eye for the Straight Guy and Will & Grace that he seemed to be able to find any. He surreptitiously watched these shows on the basement big screen, sitting as close as he could and keeping the volume as low as possible to avoid detection by others in his family. He was both transfixed and reassured by these “worlds so far away from what I knew.”

It was Brorby’s yearning for alternative stories and ways of living in the world that also drove his passion for reading and writing. And it’s a testament to his genius as a writer that he manages to evoke in us the same sense of wonder he felt when the world of books and writing was first opening up to him. When he describes his experiences reading Steinbeck and Orwell for the first time, they’re just as transcendent for us as they were for him; and he recounts key moments in his college and graduate school reading journeys with equal poignancy.

Brorby’s post-high school years were a time of both triumph and travail. On one hand, he relished the broadening of his horizons. His college brimmed with exactly the type of diversity he had ached for so badly in high school. He finally found his tribe; he formed true friendships and dated. He experienced gay culture and big cities for the first time outside of TV shows. His studies into ecology, history and literature opened up equally exciting new vistas of insight into the word. On the other hand, he struggled with suicidal thoughts and bouts of binge drinking that alienated him from his friends and even led to illegal behavior. His unflinching honesty about these struggles lends an endearing vulnerability to his story. His priority is truth, not self-flattery.

Some of the hardest parts to read in Boys and Oil have to do with the steadfast refusal of Brorby’s parents to accept him for who he is. When he first came out to them, they reacted with horror. Eventually this gave way to a sort of quiet dismay that resulted in Brorby and his parents mutually drifting apart. Still, Brorby resists the urge to caricature his parents as villains. He acknowledges their unfailing support of him in school, and describes fond memories of his dad teaching him to sketch and his mom introducing him to the wonders of baking soda volcanoes. He also treats them with admirable grace in his acknowledgements section: “My parents, who’ve had a difficult journey, but who tried.”

This book is a masterclass in showing rather than telling. It doesn’t moralize about homophobia in rural America; instead, it makes us feel the terror of Brorby’s own brushes with homophobia through expertly crafted scenes that use tension, suspense and relief to full effect. It doesn’t lecture us about the destruction done to the environment and people’s lives by the oil fracking boom, but rather shows us these realities as Brorby has witnessed them in the course of his activist crusade against fracking.

At the heart of Boys and Oil is a satisfying, surprisingly relatable arc that sees Brorby realize his lifelong dream of belonging. Along the way, we’re treated to endlessly fruitful excursions into ecology, literature, natural history, the wilds of the Great Plains and 1990s pop culture, among many other things—all couched in lyrical, moving prose. Though the author sometimes gets carried away with his wondrous descriptions of nature, the handful of occasions on which this occurs barely detracts from the book’s fine quality overall. On the whole, if you love memoirs and just plain great writing, you’ll love this book.