When will those occupying spaces of “power” ever get the message right? As the world faces a worsening food crisis – the third in 15 years, experts say – one would think that a convening of so many governments as we saw at the “Uniting for global food security” conference in Berlin in late June would result in strong and smart actions. Nope. Instead, we get a couple of new coalitions, a bit more money on the table and a lot of business as usual. It’s nowhere what’s needed to turn the crisis around.

A lot of new data and analysis have been coming out the last few weeks which give us a better understanding of what’s going on and how we might deal with it. Here are some key things we’ve learned.

We face a price crisis, not a food shortage: Food prices have been rising all around the world together with, and partly because of, energy costs. These price rises hurt the poor and the vulnerable the most. But there is no food shortage. Some countries, like China or India, have ample food reserves as a food security strategy – and they should be allowed to do so, despite ongoing debates at the World Trade Organisation about whether and how food reserves and export bans distort trade. But the overall effect of our increasingly industrialised food systems is specialisation, overproduction and tremendous waste. Some 60% of the wheat produced in Europe goes to animal feed, while 40% of the maize grown in the US is turned into fuel for cars. On a global level, 80% of the world’s soybean crop is fed each year to animals while 23% of the world’s palm oil is turned into diesel. Countries like Vietnam, Peru, Côte d’Ivoire and Kenya devote a massive amount of resources to growing and exporting farm products that are not essential, like coffee, asparagus, cacao and flowers. Meanwhile, countless hectares around the world are used to produce crops for processed junk foods totally devoid of nutrition. We don’t lack production, globally speaking. But we do have high prices, plus labour and distribution problems.

Unfortunately, lobby groups have instrumentalised the crisis to try to roll back agricultural policy reforms and climate objectives arguing that we need to produce more. The European Union’s new Farm to Fork strategy, which aims to better align farming practices with sustainability imperatives, has been put into question due to these pressures. Debates have also erupted in numerous countries about whether or not to lift biofuel mandates, aimed at lowering climate emissions, in order to allow crops to be used for food instead. (At the same time, high prices at the pump are driving investors to reactivate biofuel production in places like Brazil.)

The causes are more structural than the war in Ukraine: Many political leaders are blaming Russia for rising hunger, for ideological purposes. It is true that Russia is currently blocking exports of grain, oilseeds and fertiliser from Ukraine, as well from its own shores. (Western governments insist that these goods are exempt from their sanctions.) But wheat and sunflower oil from Russia and Ukraine can be substituted by other sources and other types of grains and oils. The deeper problem is that some countries – such as Egypt, Senegal or Lebanon – are highly dependent on these two nations for their imports. They are the ones that, in the long term, need to find alternate solutions, preferably by supporting their own small scale farmers to build diverse local agricultural systems and by strengthening regional markets.

About 20 countries source more than half their wheat from Ukraine and Russia. And just seven countries plus the EU represent 90% of the world’s wheat exports. No wonder, then, that as few as four companies (Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus) account for the bulk of this trade. While some of it is disrupted due to the war, the biggest rise in hunger is concentrated in countries themselves affected by conflict, such as Afghanistan, Yemen, Syria, Eritrea, Somalia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. This is not related to the situation in Ukraine. “Stop spreading fake news, Africa doesn’t need Ukraine’s wheat,” Malian peasant leader Ibrahima Coulibaly hammered recently. He was reacting to the war being used as yet another excuse to push Western agricultural imperialism, which has destroyed forests, farmland and food diversity across the global South.

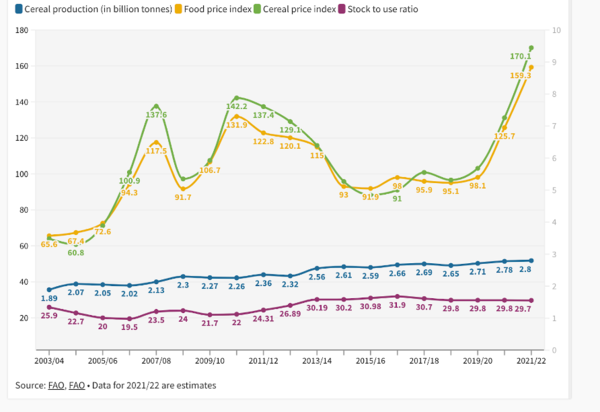

Speculation is a big part of the problem: Data now available shows that the current food price crisis did not start with the war in Ukraine but as a result of a wider set of problems. These include the Covid-19 pandemic (with the disruption that it brought and continues to bring to international supply chains), the climate crisis and speculation on financial markets. Graph 1 shows quite clearly that the rise in food prices is disconnected from production and supply, which are stable. Why is that? In part because investors – be they banks, pension funds or just individuals – are buying shares of funds that allow them to bet on future commodity prices, with real world effects on the current price of the commodities. This is well documented and known to governments. In fact, it’s similar to what occurred in the 2007-2008 food and financial crisis. The problem is that efforts to regulate these funds have been sabotaged by the finance industry itself in influential markets such as the United States and Europe. This kind of commodity speculation is even being detected on Chinese stock exchanges now.

Food prices (yellow and green) are disconnected from production and stock volumes (blue and purple). Source: The Wire, May 2022

Food prices (yellow and green) are disconnected from production and stock volumes (blue and purple). Source: The Wire, May 2022

Political parties and civil society coalitions are calling for limits on the number of commodity contracts that financial investors can hold. This would seem to be the least one could do. Right now, investors running away from Bitcoin, a major cryptocurrency which has lost more than half its value in the last few months, are reportedly moving over to agricultural commodities to make money. Others are saying we could tax these financial transactions or require that voluntary withdrawal from commodity markets be a criterion for meeting good investing credentials. But the fundamental lack of transparency that these markets are built upon is a huge problem.

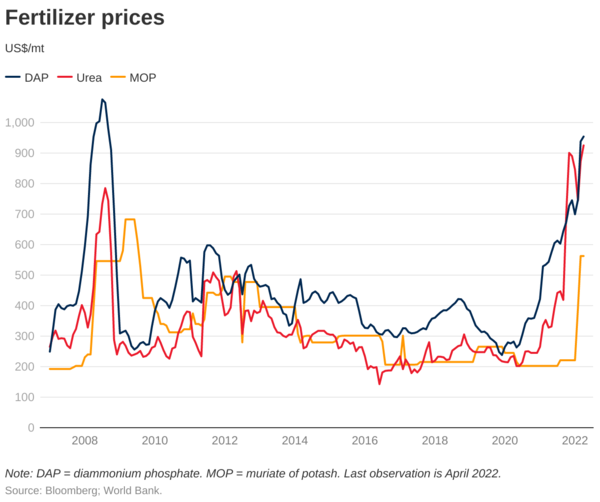

Shortages could ensue: Farmers around the world are grappling with a doubling and even tripling of prices for inputs, especially chemical fertilisers, as can be seen in Graph 2. This is compounded by rising interest rates on the credit farmers typically borrow to purchase inputs, as well as by the high costs of fuel – another major input for farmers. Many farmers have little choice but to cut back on inputs and this means harvests will decline. Consumers can’t shoulder the spiraling costs of food production either. The result could be a catastrophic collapse of both ends of the food system.

Fertiliser prices have rise dramatically since 2021. Source: World Bank, May 2022

Fertiliser prices have rise dramatically since 2021. Source: World Bank, May 2022

In the short-term, governments must step in with subsidies for basic foods. If they don’t, people will increasingly take to the streets, as we recently saw in Ecuador. Yet the problem for many governments is that they are already heavily burdened with debt, and it will be difficult and costly for them to turn to subsidies, without coming under fire from their creditors, whether public lenders like the International Monetary Fund or private investment firms like BlackRock.

Inputs aside, disrupted, shifting and extreme weather patterns as a result of climate change are already making food production more complicated and difficult. In India, heatwaves are driving grain yields down and food prices up. In Kenya and the US, livestock are dying due to climate-driven distress while, globally, soils are being destroyed, generating much more risk for the food supply. Thus alongside the immediate fight for subsidies, actions should also be taken to shift agricultural production as quickly as possible away from a reliance on chemical inputs. This is something that is urgently needed to deal with the climate crisis anyway.

We can fix this

So how do we move forward? Numerous governments and central banks are trying to tame overall inflation through monetary policy while buffering the impact on people through social safety nets. Those that met in Berlin in late June agreed to put some more money to help support and protect the most vulnerable. But we need more radical and fundamental action.

► The vulnerability of our food systems to financial speculation has to be a priority. There are many measures that could be debated to not simply close some loopholes but actually ban certain actors and instruments from dealing in food – and speculating with food prices – altogether. These should go hand in hand with long called-for moves to enforce anti-trust legislation, weed out corruption, including price gouging, and allow public control over food prices.

► Building food sovereignty is the next crucial task. Not in the sense of nationalism, borders, jealously guarded stockpiles and isolation. The cracks in our food systems are coming from the industrialised segment, with its focus on a few commodities, massive scale production, uniformity and the dispossession of workers and local communities in order to make and keep food supposedly cheap. This is the production system that cannot withstand climate shocks while it continues generating enormous social and ecological harm. Food sovereignty, which relies on sustainable production methods and practices solidarity, is the best defence again financial speculation and corporate control in our food systems.

► Social movements like La Via Campesina, and women’s networks like the Asia-Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development, are also developing innovative proposals about how to redesign international trade rules and institutions so that they really serve food systems that can feed us – supporting small scale food producers and vendors – rather than the other way around. This requires moving away from the current regime of free trade agreements and investment treaties. But rethinking how we organise trade, and making it subservient to the needs of local food systems, also means putting in place urgently needed measures to ensure access to land, especially for youth and women.

► Given the debates around the current crises, not just food, it is abundantly clear that social goals and the common good have to take priority. This means that we need to move away from the currently dominant role played by corporations. For all the talk about corporate responsibility and accountability, what we continue to get are false solutions, greenwashing and ongoing destruction while their profits keep rising. As corporations are the ones pushing chemical inputs and reliance on fossil fuels, it is really time to change strategy.

There are tonnes of good ideas on the table about how to reshape our food systems – and fleets of social movements eager to take the reins and put them in practice. Perhaps this food crisis can serve to bring movements together to get some serious action going.

Teaser photo credit: Breadman. Photo: Mohanad5ayman, Commons Wikimedia