At the end of April, I attended my first in-person conference since the fall of 2019. And I have to admit it brought me a lot of joy! It helped that it was a short drive away—at the Harvard Divinity School—so little carbon was expended to get there. Cambridge is beautiful, the school opulent, and our little bed & breakfast (the cheapest I could find within walking distance to the campus) turned out to be really nice. But really, the highlight was simply being around other people—in person—who understand that life and Earth are sacred and deserve reverence. I can’t recap everything but these are five key lessons I took home.

Play, play, play!

I love to play. Albeit in certain safe contexts. With my son? Yes. Board games? Absolutely. But I’m overly serious when it comes to Gaianism. I think, as this is a new religion, I’m trying too hard to be serious: to avoid it from being labeled as new age or a hippy-dippy fad. But throwing away play in that process is foolish, a lesson I’m learning as I’ve started teaching a Forest Bathing 101 class, where I intentionally add one playful or “imaginal” exercise each session.

There was one workshop that was all about those types of exercises and the value of being open to play. The instructor, Henry Kramer, asked some really challenging questions: like why did we stop playing? Why can kids create whole worlds with the materials in their lives—like the animated companions stuffed animals become—and we cannot (or choose not to).1 Whether real or not, isn’t the world more alive if we act as others are?

Now you can probably see why I’ve been trying not to go there. I want Gaia to be at the center. But is that better than imaging every tree, rock, and river has its own soul? As in Shintoism or perhaps Paganism? I hesitate, because of my silly attachment to science and what can be explained, but as Kramer noted, are we losing something magical when we see a stuffed animal, a tree, or a spider as just a stuffed animal, tree, or spider?2

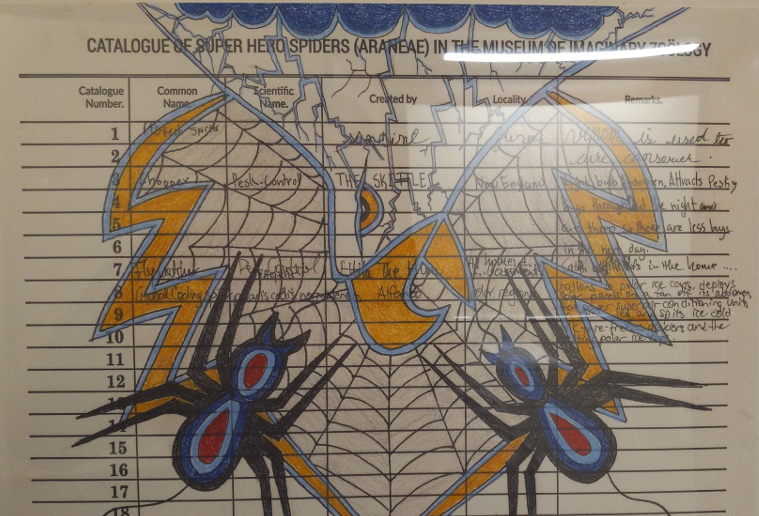

Turns out the spider and dragonfly are friends with the Thunderbird. Drawing: “Supernatural Friends” by Butch ThunderHawk. (Photographed by Erik Assadourian)

Embrace the magic?

In his talk, John Halstead noted the three overlapping circles of paganism: magic, gods, and Earth, and that the overfocusing on magic instrumentalizes Earth and redirects this ecocentric religion to a more egocentric one. Halstead asked the inverse question to me during my presentation: is Gaianism too cerebral? Is there a space for the mystical? While I don’t want to go down the path of overly mystifying (or using psychedelics as a mechanism to connect with Gaia—actually the subject of another talk at the conference), I do hope one day Gaian traditions will take root, influencing the broader culture and opening a way for countless people to have a deeper life experience. Perhaps that’ll come through nature immersion, or some uniquely Gaian tradition that evolves (perhaps hibernating—or as future scientists might call it “extended trance meditation”—with bears?). Only time will tell! The bigger point is this reinforces again the need for play, experimentation, and embracing our non-cerebral interactions with Gaia: what Patrick Curry would call enchantment.

It’d be a tight squeeze, but I’m sure it’d be quite the mystical experience. (Image from U.S. Forest Service via Flickr)

Don’t appropriate

One talk I went to focused on the New Age appropriation of smudging (the Indigenous custom of cleansing oneself with smoke) and crystal healing. According to the presenter, Larissa, there is such a demand for sage now that Peru stopped exportation. She went into depth into the exploitative labor practices in the crystal mining industry (mostly children, paid nearly nothing). This made me very happy that Gaianism has not adopted any New Age trappings! Crystals, Larissa noted (just in case it wasn’t clear), work through the placebo effect. That said, I’m not against effective use of placebo—you could argue it’s play in service of healing. However, this play shouldn’t damage Gaia or others in the process. Larissa gave great tips on how to prevent impact and appropriation. Burn bay leaves, rosemary, or other locally available and abundant herbs for smudging (and not ones appropriated from Native American rites). And use locally harvested rocks. As crystal healing is based on color alignment with chakra colors—no comment—one could find a colored rock in the woods that calls to you. If this is an imaginal exercise—a means to concentrate on one’s discomfort—then this might be even more effective: you’re focusing on seeking out a cure for your malady (exercising your agency rather than buying the solution); you’re getting outside and moving; and then you’re taking that found rock partner and focusing on it to help in healing. I can imagine the placebo power of that would be far stronger than purchased crystals mined by impoverished children.

As for appropriation, one speaker, Billy J. Choi-Gekas asked specifically, “How does your method and theology benefit at the expense of marginalized groups?” As with the recent discussions on racism—we’re all racist no matter how much we try to be otherwise—no matter how cautious or transparent we are as Gaians, it is inevitable that we borrow and appropriate.

I certainly see appropriation of Indigenous ways in forest schooling and I value Indigenous and ancient wisdoms, to the point where I argue for intentional borrowing (such as here). But the key, I think, is to do so with humility and transparency. And, not just artificial transplanting, but evolving borrowed practices to the new context in which they are set. I’m not sure that’s enough but this philosophy is certainly still actively evolving, so the key point is to keep asking the question Choi-Gekas raised.

Yes, they’re pretty, but how exactly are they supposed to help? (Image from Aline Ponce via Pixabay)

Engage, engage, engage

Not only did it feel great to drink from this font of diverse knowledge, as well as sitting unmasked in a roomful of peers all interested in ecological spiritualities, but it was an important reminder that much of my, and other Gaians’ time, should be dedicated to sharing this way. That especially hit home at certain moments in the conference, for example, listening to a talk by Mark Ferrara about the loose spiritual practices at Ecovillage Ithaca.

It became clear that the residents, who went out of their way to live in an ecologically minded community, were struggling with the same questions on how to make this commitment overt, ongoing, and sacred. Ferrara shared several listserv messages that made this clear: invitations to do a darkness meditation on solstice; to take meditative walks; quotes and practices from other traditions; and so on. It became apparent to me that the culture creation process is essential, as is the organizing: the regular cultivation of norms and practices through regular engagement. It also made it clear that we, Gaians, have a lot of work to do in reaching out and sharing our Way (not to mention solidifying our practices!).

Happily, a few people after my talk said they might be Gaians too, which is a good reminder on the value of sharing the Gaian message regularly. One regret: the Divinity School was covered in posters of all types: weekly meditation sessions, “contemplative birdwalks,” even spiritual ice cream socials. It would’ve been perfect to put up some Upcoming Gaian Events posters!

Curious about what I said? You can check out my talk on the Gaian Way here. And all other talks can be found here (at least for a few weeks from posting).

We are a vast minority

It was great to connect with others who identify as eco-spiritually minded individuals, but there were a few reminders that this was an oasis of understanding in a desert of disconnect. Perhaps most symbolic was the spraying of grass by Harvard grounds crew. I hope it was just seed, coloring, and fertilizer as the crew was completely unmasked and students and conference participants were all around during spraying. But even so, is this really what Harvard needs? Acres of monocropped turf, maintained and sustained with countless fossil fuel inputs (trucks, mowing fuel, fertilizers, etc.). I’m sure that money could be spent better elsewhere (like garden plots and permaculture landscaping that is more beautiful and draws pollinators, birds, and other life to the divinity school campus), and I’m sure the Charles River would be better off without the run off.

Don’t get me wrong, looking afterwards, HDS states very clearly that sustainability is important to its mission and lists the many ways it’s engaging with this (which are generally impressive). But of course, it’s far from enough. So even while there were beautiful reminders of our connection to nature at this conference—talks, posters, and so on—there was, and will continue to be, far more reminders of our broken relationship, which Gaians and other ecologically spiritually minded folk should, and I hope will, continue to work toward healing.

Not the best use of hydrocarbons Harvard’s money can buy. (Image by Erik Assadourian)

Not the best use of hydrocarbons Harvard’s money can buy. (Image by Erik Assadourian)

Endnotes

1) Kramer shared a quotation that we both heard in an earlier writing workshop led by Claudia Ford: “animism is the only sensible version of materialism.” Along with that, I also joined a prayer writing workshop. Both were filled with good tips on writing, including playfully, and will certainly end up shaping future reflections (and Gaian prayers).

2) There was another inspiring talk by Sarah Karikó, a Harvard arachnologist, artist and Research Director of Gossamer Labs LLC. She explored her work with spiders—not just studying them but how she has shared her love of spiders with the broader world. For example, she created a program where she explored spider adaptations or superpowers with children and their families at pediatric oncology wards, then had them think about something in the world or in their own life that they could use a little extra help with and invited them to create a spider super hero to help out.