Fossil fuels have leveraged human power and ingenuity to a remarkable degree. Their discovery and accelerating utilization utterly transformed lifestyles, achievements, and even how we perceive ourselves as a species.

Yet, one thing we know for certain about fossil fuels is that they are a finite resource on this planet—slowly developed in select locations over hundreds of millions of years and being used about a million times faster than the rate of production. We know that we have already consumed a sizable fraction of the initial inheritance: perhaps now halfway through the irreplaceable allotment of oil. So we know that this phase of the human adventure is a temporary one.

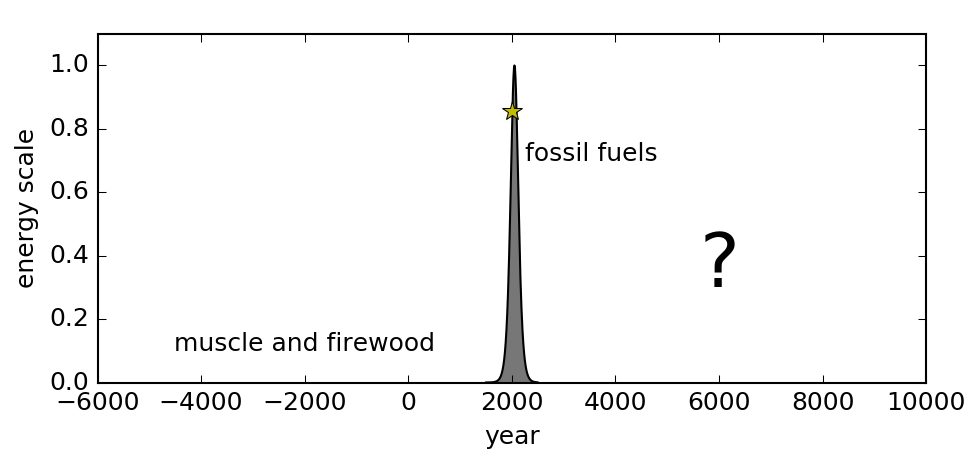

The quintessential graphic for conveying this idea is one I have used many times, because I believe it is the most important plot modern humans could possibly absorb. Human energy use has shot up in the last 150 years, and in the context of fossil fuels will plummet on a similar timescale, leaving—what, exactly?

The fossil fuel energy explosion that powers our current fireworks show is a momentary phenomenon that will be over in a historically short time.

Over timescales relevant to civilization (which began 10,000 years ago with agriculture and cities), plots of almost anything relating to human activity look like hockey sticks: population, agricultural output, industrial output, mined materials, deforestation, species extinctions, and so on. Many of these certainly correlate to population growth, but the per capita impacts also have shot up, compounding the human footprint to a frightening degree. At this point, humans and their livestock account for 96% of mammal mass on the planet, leaving a mere 4% for all wild animals (half of this from massive whales and other marine mammals). It’s not just a footprint any more: it’s a boot on the throat of the planet, leaving non-human life gasping and silently begging for even a little mercy. Is anybody getting video of this?

Almost all of this explosive impact can be traced to fossil fuels, which I have started visualizing as a suit donned by humans that has given us literal superpowers. What would we be without our fancy suit?

It’s All Based on Fossil Fuels

The fossil fuel suit epiphany was partly stimulated by recognizing that we have not built a single hydroelectric dam of any consequence without the aid of fossil fuels. No nuclear plants, wind turbines, or solar panels have been made without the bulk of the work (energy) required coming from fossil fuels. From mining to earth-moving to materials processing to transporting ingredients and final products, the renewable/alternative energy enterprise has been a fossil endeavor through and through.

So when you look at plots of global energy trends, seeing fossil fuels towering over the diminutive-but-rising renewables, recognize that even those alternatives are just a ghostly reflection of fossil fuel use.

That in itself is not particularly problematic. Based on the favorable energy return on energy invested (EROEI) in renewable technologies—well above break-even—it is possible and beneficial to leverage fossil fuel use into non-fossil forms. This non-fossil augmentation could be treated as a form of efficiency. Rather than getting 100% of our energy from fossil fuels, we get only 80% in direct form and squeeze another 20% out of other fossil-enabled resources.

The bigger problem is that the processing of industrial materials (cement, steel, aluminum, etc.) requires a great deal of heat, which currently is obtained by burning fossil fuels. Almost all alternatives to fossil fuels (the exception being burning biomass) create electricity, which is not particularly suited to creating the kind of heat required in industry.

To understand this, think about the usual method of creating electrical heat. Toasters, space heaters, dryers, and stove tops use metal coils that get hot and even glow orange. But to get hot enough to melt steel, you’d also melt the coils. So that’s no way to go. Electric arcs can make small volumes very hot (think arc-welding), but only tungsten electrodes resist melting under the arc’s heat. Put simply, creating enough heat—in large volumes—to “destroy” (melt, re-form) materials will tend to destroy the heating agent as well. In the case of fossil fuels, we don’t care if the heating agent (fuel) is “destroyed” (burned) in the process of creating heat: that’s what we do with them in any application. But we don’t want to destroy electrical heaters in the process of creating enough heat for an industrial application.

This view may be oversimplified, but I think it helps us understand the nature of the challenge, and why heating by burning is an entirely different animal—and much easier—than heating by electricity.

Without Fossil Fuels?

What, then, is left when fossil fuels are more scarce? One possibility is a well ordered world in which sophisticated new technology maintains our modern capabilities in an utterly transformed way. This is probably the default assumption of most, but not a carefully examined one that can be easily supported based on current knowledge/evidence: owing in part to the grossly distorted perspective fostered by the fossil fuel age. The other world is one in which life gets tougher, high technology is harder to maintain, resource wars are the most obvious and common strategies to secure basic needs, and the resulting disruptions make it difficult to achieve the utopian vision of a high-tech future dependent on global supplies. Today’s energy-rich lifestyle may well turn out to be a privilege conferred by the fossil fuel suit, as if satisfying a dress code for the high-tech club. Once the enabling elixir is spent, we may be kicked out of the club.

While we can’t know the future, one thing we can do is ask what might be learned from the past. We once lived in a world without fossil fuel use. The year 1712 marks a turning point, when the first commercial steam engine—powered by coal—was used to pump water from coal mines in order to access more coal. Did you notice a theme there? What inventions existed before the start of the fossil fuel era? Those can be truly said to be independent of fossil fuels. After this date, the capabilities afforded by an abundant energy source slowly permeated the world and opened new possibilities. How many of the subsequent inventions can trace some dependency to fossil fuels somewhere in their lineage? Hint: the flurry of inventions—as listed here—tended to come out of places that were early-adopters of fossil energy (i.e., England, Scotland, France).

It is entertaining to muse about what we might not have today if fossil fuels had never been available or utilized. Would we have computers or lasers? Would we have skyscrapers or photovoltaics? Would we have understood nuclear energy or fundamental physics that relied on high-energy experiments? Would we even have bicycles? It is, of course, impossible to say with any certainty. But since all of these things first emerged after fossil fuels took hold, and built upon each other in ways that at least had access to the benefits of fossil fuels, it is plausible that most of what we see around us in the developed world owes its existence to fossil fuels. In fact, one might say that it is a much tougher case to argue the counterfactual that we would still have comparable technology today had fossil fuels not burst onto the scene.

Aren’t We Special?

People tend to prefer the narrative that we, ourselves, are the superheros, and that our superpowers are not from the fossil fuel suit, but are cognitive in nature. Yet we have the same neural hardware (if not slightly downsized) as our prehistoric ancestors. The main cognitive revolution happened about 70,000 years ago when humans started to believe in things that do not exist (like spirits or potential future gains) that allowed large-scale coordination and shared identity to outcompete evolution’s more biophysical tricks of sharp teeth/claws, speed, strength, camouflage, poison, or overwhelming numbers. Global spread of homo sapiens and megafauna extinctions quickly followed, and it is at this point that the human experiment began to smolder: something was off. About 10,000 years ago, agriculture started and the first visible flame ignited. About 300–400 years ago, the Enlightenment lit a fuse by developing a scientific approach to understanding the world. It was not long before the fuse found fossil fuels and we now witness the predictable explosion that ensued. The explosion is breathtakingly rapid on any meaningful timeline, only appearing in slow motion to the few generations experiencing the phenomenon and thus seeming “normal.”

So we can trace some part of our current planetary dominance to human ingenuity, but perhaps the lion’s share actually is attributable to the energy bonanza—as suggested by the dramatic change in the pace of innovation before and after the fossil transition.

For most people, however, the critical role fossil fuels played is easily overlooked. In so doing, we form a grotesquely warped view of who we are. Anything seems possible: we would appear to have transcended nature to be the masters of the planet. Lots of self-assigned rights and privileges follow. It is an age of human exceptionalism. The resulting narrative is highly appealing and stubbornly held even when cracks in the foundation are evident. Many fewer life-changing inventions have entered the scene in the last 60 years than in the 60 years prior to that. Such an inconvenient and obvious truth threatens deeply held beliefs and is quickly brushed aside as anything but obvious.

That leaves the question: if most of what we praise about ourselves is not so much us but our fossil fuel suit (we do look good in it, don’t we?), then what’s left when our empire loses its cladding? Just how feeble, pathetic, and dull are we, under that thick and powerful shroud?

I am not claiming to have a definitive answer, although it is clear where my suspicions lie. The fairest thing to say is that we do not really know. We don’t know what will be possible in a world beyond fossil fuels. I would rest easier if more people acknowledged this constructive uncertainty. Decisions about the future will simply be better if admitting limitations to resources and to our own capabilities, while pulling back from some intoxicated vision of human triumph over nature.

Teaser photo credit: From Pixabay (Ramdlon)