Walk into any store, here in Ireland or anywhere in the modern world, and you are quickly overwhelmed by thousands of products screaming for attention. Almost all these products, though — shoes, CDs, deodorants, toys — have one thing in common: they break quickly and are meant to be thrown away and replaced. All of them will become less replaceable as they cost more to make in Third-World factories and transport around a planet. Yet for most of human history people didn’t have mountains of throwaway goods; rather, they made what they needed, and invested in things that lasted.

What we all need to invest in, then, is durable goods that require little technology to make or repair, and the knowledge to use them. Ironically, this often means re-adopting “obsolete” technology that was more common fifty or a hundred years ago.

Take the straight razor. It costs much more initially than a plastic disposable razor, and using it requires some practice, but properly maintained it can last indefinitely; a razor bought today could be passed to children decades from now. Or take slide rules, which can calculate almost as fast as a person with a calculator; some of the calculations for the first space launches were done with slide rules. Less than fifty years ago the dictionary entry for “computer” was a person who computed with a slide rule, yet most people now have not only never used one, they have often never heard that such things existed. Washboards and wringers would allow clothes to be cleaned without electricity and dried quickly, yet I have yet to find any, as they are too old for stores and too mundane for antiques dealers.

Other things like bicycles, clocks or acoustic instruments can run on no electricity or fossil fuels, but they do need to be maintained, and often require at least a bit of functioning industry to create. Bicycles, especially, require rubber tyres and paved roads – it was mostly for bicycles that roads were paved, even before cars. Clockwork mechanisms, also, can be used for all kinds of things beyond telling time, but there are no industries to sustain it yet.

Even foil solar ovens require some industrial energy. We forget how recently aluminium foil was an exotic and rare commodity – well into the industrial age, the U.S. government almost covered the newly-built Washington Monument with shiny foil to show what a wealthy country they were. Even with devices that require electricity, simpler is often better. A vinyl album can be played with a cactus needle if the real one breaks, and even if there is no electricity, one might be able to hook it up to pedals or a clockwork mechanism.

In some cases — musical instruments, pottery wheels – the knowledge and techniques are more important than the items themselves. Take, for example, knitting. The first references to knitting were in the Middle Ages, but there is no reason to believe that Stone Age people could not have knitted. As far as we know, they did not – the technique had not been invented.

The same is true of recent inventions that were never widely publicised, like hot composting. By getting the right mix of carbon-rich and nitrogen-rich material and aerating your compost, you can cultivate the types of bacteria that generate lots of heat – I’ve taken hot showers in the middle of a cold Irish morning, connected to no burners and no electricity, just a compost heap. We could use this to heat our homes, if only more people knew it existed.

I don’t anticipate the industry to create these things vanishing in my lifetime — and hopefully not ever — but the energy and political stability to create these things will continue to decline around the world, and in the USA particularly as it loses its superpower status, and the sooner we rebuild the local industry to make needed things, the better.

Thankfully, most of the infrastructure for this already exists; when I was a newspaper reporter covering small towns in Missouri and Kansas, I noticed many towns had an abandoned factory, train station and rail tracks, now covered with graffiti. Rather than everyone becoming individual survivalists, we would be better served by restoring some of this basic infrastructure to once more create things that last.

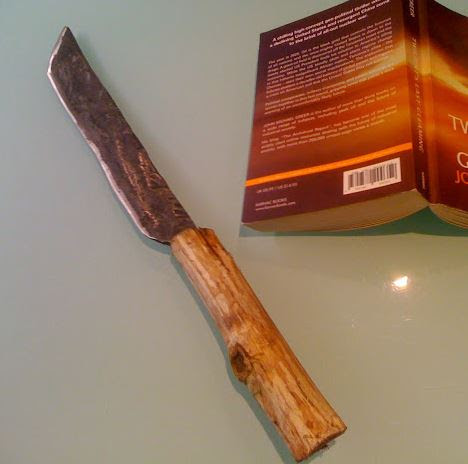

The knife I created on the forge, with a book for size reference. It used to be an old car part. Photo by Brian Kaller (2022). Used by permission.

The knife I created on the forge, with a book for size reference. It used to be an old car part. Photo by Brian Kaller (2022). Used by permission.

Teaser Photo: A forge we created from old fertiliser bags, mud and horse manure. Photo by Brian Kaller (2022). Used by permission.