Ed. note: To kick off our curated series The Dirt on Soil, we are starting out with a big-picture look at the world of sustainable food systems, framed by author and researcher Laura Lengnick. The body of the piece is excerpted from the updated and expanded 2nd edition of Laura’s book: Resilient Agriculture: Cultivating Food Systems for a Changing Climate, published by New Society Books, and published here on Resilience.org with the permission of the publisher and the author. The book will be released on June 14, 2022. You can find out more about the book and pre-order it here.

Ed. note: To kick off our curated series The Dirt on Soil, we are starting out with a big-picture look at the world of sustainable food systems, framed by author and researcher Laura Lengnick. The body of the piece is excerpted from the updated and expanded 2nd edition of Laura’s book: Resilient Agriculture: Cultivating Food Systems for a Changing Climate, published by New Society Books, and published here on Resilience.org with the permission of the publisher and the author. The book will be released on June 14, 2022. You can find out more about the book and pre-order it here.

My first big step into the world of climate action came in 2011. In April of that year, I was invited to join the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) leadership team responsible for producing the very first national report exploring adaptation to climate change in U.S. agriculture. As a member of the lead author team and the lead scientist on adaptation, I worked with more than 60 researchers all across the U.S. to gather, review, discuss, and report on the state of scientific knowledge about the effects of climate change on U.S. agriculture. We also reported on what we knew about how best to maintain agricultural production in a changing climate.

It was in the process of doing this work that I discovered – much to my surprise – that the voices of American farmers and ranchers were completely missing in climate change adaptation research and planning. Our USDA team was able to draw on adaptation research carried out with farmers throughout Europe, Australia and Canada, but none from the U.S. I resolved to change this. Over the next two years, working at night and on weekends, I listened as longtime sustainable farmers and ranchers from all over the United States shared their experiences of producing crops and livestock at the frontlines of climate change.

Why longtime? Because I knew that climate change effects began to accelerate in the U.S. around the year 2000. I thought that farmers and ranchers who had been farming in the same location since at least 1990 would be the most likely to have noticed this increase in weather variability and extremes.

Why sustainable? Because I thought all producers using agroecological practices – including conservation, organic, holistic, biointensive, biodynamic, regenerative, carbon, and climate-smart farmers and ranchers – offered at least three valuable real-world tests of resilience principles. First, their use of an “ecological logic” required them to produce crops and livestock without depending on large imports of resources or exports of waste. Second, farmers and ranchers using agroecological principles have been largely left to figure out how to do this on their own without the help of “the experts,” so they offer an interesting test of the resilience principle that local innovation – designing within the limits of place – cultivates response, recovery and transformation capacity. Finally, I knew that their choice to manage healthy farm ecosystems left these producers ineligible for most of the support programs available to other farmers. This meant that they had no choice but to design and manage for resilience just to stay in business — they were farming without a safety net.

Why all over the U.S? Because the changes in seasonal weather patterns associated with climate change were not the same everywhere. The Midwest and Northeast were getting wetter, while the Southwest was getting drier. Average temperatures were rising in most of the U.S., but parts of the Southeast were getting cooler. These different patterns of change meant that farm location was an important factor in how a producer experienced climate change.

Last year, I checked back in with these producers to hear how they were doing and what they had learned over the last decade about managing climate risk. To round out my research, I also listened to other longtime farmers not included in the original survey, along with some less experienced farmers as well.

The stories that I share in the 2nd edition of Resilient Agriculture represent a diversity of answers to one of the most important questions of our times: How do we feed ourselves in a world on fire? These are brave stories, being lived by real people who have made the choice to grow food in a way that promotes healthy land, people and community, despite the many barriers created by global industrial food. These farmers and ranchers do much more than simply grow high-quality, nutrient-dense whole foods using agricultural practices that have restored the health of their land. They all reach beyond the farm and into the food system to support resilient foodways in the places they call home. Together, these stories weave a rich tapestry of place-based wisdom accumulated through lived experience – failures that teach, successes that inspire—that can help guide us through the many challenges on the path to a resilient food future.

This excerpt from the second edition explores some of the lessons learned in the contemporary sustainable food movement, a movement that – although incomplete and imperfect – has devoted considerable effort to understanding what it means to feed ourselves without harm to land, people and community.

From Land to Mouth: In Search of Sustainable Food

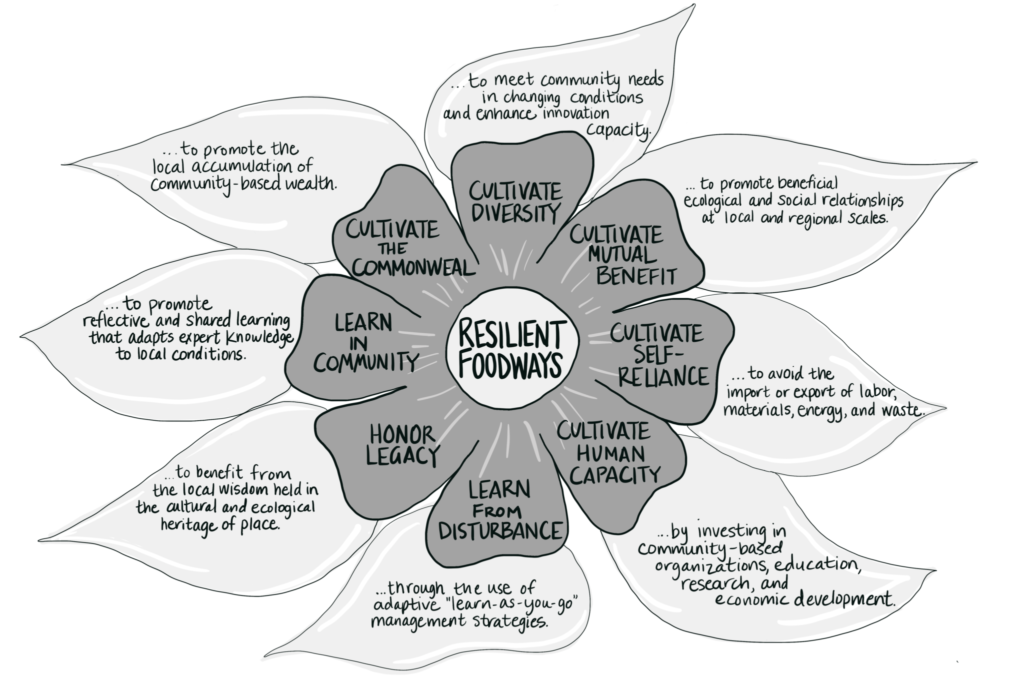

Foodways that express these eight behaviors tend to have high response, recovery and transformation capacity. Credit: Caryn Hanna. Figure 14.1, in Resilient Agriculture: Cultivating Food Systems for a Changing Climate, 2nd Edition, June 2022.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, a growing awareness of the environmental, social and economic harms of industrial food systems drove a search for solutions that emerged as the sustainable agriculture movement. Defined by the U.S. Congress in 1990 (1) and supported by a new federal program—the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program–much of the early investment in sustainable agriculture was focused on collaborative, on-farm research and development devoted to addressing regional farming needs. As the movement gained momentum, attention shifted to reimagining the food system in response to the increasingly globalized, concentrated and corporate-controlled food system that presented formidable barriers to the widespread adoption of sustainable agriculture.

The sustainable food movement created a space to examine the sustainability challenges of industrial agriculture. A space that eventually came to include the whole of the global industrial food system-from land to mouth-in the search for sustainable solutions. A search that would eventually come to draw on the wisdom of the many cultures who know how to live well within the ecological limits of the places they call home.

Indigenous Foodways For millions of years, Homo sapiens worked in community to feed on the plants and animals that lived in the lands they called home. Satisfying this basic need to eat drove the evolution of a wide diversity of foraging strategies shaped largely by local ecological conditions. In diverse ecosystems across the Earth, humans, like all animals, were nourished as part of the native food web. Archeological evidence suggests that by the end of the last ice age, about twenty thousand years ago, humans had evolved a good life based on foraging. Food foraging sustained stable, healthy human populations for millennia, but about ten thousand years ago, in different places around the world, the human population began to grow. Wherever that happened, people began to change the way they ate.

At different times within the Neolithic Period (10,000–2,000 BCE) and at different places around the world, foraging cultures slowly evolved one of three distinctly new foodways that included the careful cultivation of specifically selected and improved plant and animal species. (2)

In the desert grassland biomes of the world, where conditions are too dry for the cultivation of plant foods, people first hunted grazing animals and then domesticated some-sheep, goats, cattle and camels to sustain themselves with a type of foodway that anthropologists have named pastoralism. In wetter forest biomes, horticulturalists began to cultivate the wild plants and animals that they depended on for food in forest clearings that they rotated through the landscapes of their home. On the fertile floodplains of the great river valleys in the world’s savanna biomes, sedentary agriculturalists began to cultivate wild grains and grazing animals in permanent settlements. Even though these new foodways evolved in very different ecological circumstances, they share a number of characteristics that offer important examples of how to feed ourselves within the ecological limits of place.

First, all are embedded in local ecosystems and depend on healthy ecological processes to provide water, nutrients, pest suppression, waste disposal and other services needed to deliberately manage plants and animals for food. In every essential way, these early systems of agriculture were well-adapted to local ecological resource limits.

Second, all of these foodways took advantage of the many benefits associated with keeping livestock. Most importantly, these strategies recognized that animals are an efficient strategy for producing food from plants that are inedible to humans, for gathering and storing foods, and for utilizing food wastes. The ruminant animals-sheep, goats, cattle, camels-convert inedible grasses and forbs into high-quality meat, milk and eggs for human consumption, while others-dogs, swine, poultry, can consume a wide variety of foods and serve as garbage collectors and recyclers. Animals also function as efficient “biological silos” for storing excess production for later consumption. Ruminants are particularly use ful in this regard because they can survive for long periods without food.

Third, along with food, these Indigenous foodways produced another important product: an energy profit. Each produced more food energy than the energy expended in production, although none came close to the energy profit estimated for foraging of about 40 calories for every labor calorie invested. Pastoral and horticultural foodways yield about 11 calories, and sedentary foodways about eight for every calorie of labor (mostly human) invested. In comparison, industrial agriculture flips this energy relationship on its head. Instead of an energy profit, industrial agriculture produces an energy deficit that ranges from about seven calories invested for every vegetable calorie produced to about 32 calories invested (mostly as fossil fuel energy) for every calorie of beef produced. As a whole, it has been estimated that the U.S. food system requires about seven calories of energy to produce one calorie of food.

Ultimately, the problem of feeding our species boils down to a question of how best to manage five basic agricultural resources: land, water, energy, animals (including people) and plants. Pastoralists focused on managing livestock because grasslands have few native edible plants and shifting, uncertain rainfall. However, grasslands have a lot of grass and mobile grazing animals whose milk, blood and meat provide sustenance to humans. Horticulturalists did not have the benefit of large domesticable animals but had the advantage of large expanses of biodiverse forests and plentiful rainfall, and so they focused on cultivating food forests and woodland animals. Sedentary agriculturalists had the advantage of a diversity of edible grasses and other edible plants, regular flooding to regenerate crop nutrients in the soil, and large domesticable animals and so they developed agricultural systems that depended on both.

Thinking about the lessons these early foodways teach us raises some questions about how we might reimagine the global industrial food system that feeds us today. What if we could figure out a way to feed ourselves that recognizes and takes advantage of regional ecological limits? What if we could figure out a way to feed ourselves without the need to import nutrients, water and pesticides or export wastes? What if our foodways could again produce an energy profit along with nutrient dense, culturally vibrant whole foods for all? What if our foodways could again sustain the health of land, people and community through relationships of respect and mutual benefit? What if our foodways could enhance our commonweal? And what if our foodways could reverse climate change? These are the kinds of questions raised by those interested in exploring the sustainability of the U.S. food system.

The Good Food Movement From its earliest days, the contemporary “good food” movement has looked to sustainability principles as a way to address the growing environmental, social and economic issues created by the global industrial transformation of the U.S. food system in the latter part of the twentieth century. Sustainability inspired a generation of leaders to recognize the ecological impacts of industrialism. The power of sustainability as a driver of change is beyond dispute: within ten years of the Bruntland Commission’s definition of sustainable development, (3) environmental sustainability principles were in use by government, business and the public throughout the world.

This cultural excitement around the idea of sustainability helped to shape the earliest expressions of the contemporary sustainable food movement in the U.S., which championed broader thinking about both the intention and the effects of the new relationships cultivated by global industrial food. This work explored the potential to return to food system relationships that promote commensal community, identified the growing distance between producers and consumers as a key sustainability concern, and identified local food as the solution. (4) A multitude of individuals and organizations began to approach the question of sustainable food, each bringing valuable perspectives that enhanced our collective understanding of what it takes to sustain food and farming over the long term.

In the last decade, these different strands of thought have begun to converge in a powerful new vision of the future of food. A future that is equitable, sustainable, regenerative and resilient. It is a vision that is well within our grasp. It is a vision that–just like resilient agriculture—is already on the ground and growing, tended by people secure in their belief that we can find better ways to feed ourselves in community.

The stories shared by the farmers and ranchers featured in Resilient Agriculture show us how to cultivate this future, from the production of foods like fruit jams from Ela Family Farms, cooking oils from Quinn Farm and Ranch, Shepherd Farms pecans, drinking vinegars and hard ciders from Almar Orchards and Cidery, Rid-All’s healthy green elixirs, humus from Zenner Farms, and White Oak Pastures meats, to collaborative production, processing and distribution networks like Shepherd’s Grain in the Northwest, Hickory Nut Gap Meats in the Southeast and Strauss Dairy in California.

These producers, and many others just like them, are the people who supply your local cooperative grocery store and your local food restaurants. They are the people you see at your local farmers market, or your community-supported agriculture pickup, or at the community garden in your neighborhood. They are the people who gather at sustainable food and farming conferences every year throughout the country to share what they know about the art, science and spirit of growing, processing, preserving, preparing and celebrating locally grown foods in community. They have nourished and been nourished by decades of sustainable food activism, tirelessly working to transform the global industrial food system. Although a global movement informed by many, the stories of three movements that have come together in recent years holds particular significance for U.S. food resilience.

The Community Food Security Coalition formed out of the sustainable agriculture movement to promote community-based capacity for local food production, processing and marketing as a solution to the twin challenges of farm profitability and food insecurity. The One Health movement explores the public health effects of industrial food. The Food Justice movement works to address the structural race, class and gender inequities perpetuated by global industrial foodways. In recent years, these three movements have come together with the growing realization that it will take nothing less than the decolonization (5) of industrial food to realize the promise of sustainable foodways.

Cultivating Community Foodways The Community Food Security Coalition was a diverse alliance of over 500 organizations in the U.S. dedicated to cultivating strong, sustainable, local and regional food systems to ensure access to affordable, nutritious and culturally appropriate food to all people at all times. Using a sophisticated blend of training, networking, and advocacy centered on local food projects, the alliance served as a kind of national mutual aid collective that has been credited with the emergence of the “good food” movements in the early years of this century. (6) For almost two decades, the alliance supported innovative projects and programs designed to connect eaters to the land and to food through farm-to-school and community gardening programs, farmers markets, new farmer projects and community supported agriculture. Although founded with a goal of transformative food system change, over time, market-based, local food systems strategies came to dominate the work of the alliance.

As our understanding of community food systems matured, some of the sustainability benefits assumed by the promoters of local food came into question. (7) New research exploring the popular concept of “food miles” as a meaningful measure of food sustainability challenged assumptions about the environmental benefits of local food. When Walmart, the largest grocer in the United States, announced it would begin selling local food, some suggested that local food would suffer the same loss of integrity as organic food with the rise of “industrial or ganic.” Others offered evidence that the social benefits associated with local food networks may not survive scaling up because increasing the distance between producer and consumer erodes the social capital cultivated by direct markets.

As the community food movement continued to explore these considerations of scale and integrity, the health professions began to grapple more publicly with some fundamental questions about the growing harms of industrial food on the health of land, people, community and the planet.

From Sustainable Diet to Planetary Health Dietitians were among the first in the human health professions to explore sustainability. In a 1983 address to the American Dietetic Association, Kate Clancy proposed a “sustainable diet” to provoke discussion within the greater medical community about the impacts of industrial food. (8) Clancy’s use of sustainability as a framework for dietary guidance integrated multiple strands of thought-some old, some new-about the relationships between human and environmental health. Twelve years later, Joan Gussow was proud to note the nutrition profession’s contribution to what would become an enduring idea: the choices we make about the way we eat shape our world. (9)

During the first decade of this century, thinking about human health in the context of food systems attracted the increasing interest of other groups in the health and planning professions. Veterinarians raised concerns about the widespread use of antibiotics in industrial meat production, while public health officials and land use planners began to explore how the operating context of the U.S. food system promoted some of the most critical health issues of our times. Making the connection between how what we eat shapes the health of individuals and communities, nutritionists continued to press their own profession to recognize all the ways that the global industrial food system creates barriers to healthy food choices for all.

This systems approach to health was formally articulated in an un usual joint statement calling for food system transformation in 2010 by the American Dietetic Association, American Medical Association, American Nurses Association, American Public Health Association and the American Planning Association. (10) The statement defined a sustainable community food system as one that “integrates food production, processing, distribution and consumption to enhance the environmental, economic, social and nutritional health of a particular place.” The statement made explicit reference to “the interdependent and inseparable relationships” within the food system that create sustainable behaviors such as health, diversity, equity and resilience.

These efforts to connect the dots between food and health have matured into the planetary health movement which seeks to understand the human health impacts of industrial disruptions of Earth’s natural sys tems. (11) Among the challenges addressed by this new movement are the human and planetary health consequences of global-scale changes such as biodiversity loss, environmental pollution, urbanization and climate change. Planetary health workers seek to understand how, for example, the loss of biodiversity and continued human encroachment on wild landscapes create the conditions for new diseases such as COVID.

The planetary health movement confronts three kinds of twenty-first century challenges to human health:

- imagination challenges such as the failure to account for long-term social-ecological consequences of human progress

- research and information challenges such as the failure to promote holistic and regenerative health strategies

- governance challenges such as delayed environmental action by governing bodies because of unwillingness, uncertainty or inability to cooperate

The movement promotes collaborative research across multiple sectors of the economy that are critical to human health and well-being, such as energy, agriculture and water. The goal of this work is to provide the science-based information that policymakers need to develop and implement holistic solutions to the impacts of global environmental change.

The Planetary Health Alliance is a diverse global consortium of over 200 organizations that are committed to advancing planetary health research, education and policy. Since its launch in 2016, the Alliance has supported a wide range of sustainable foodways projects, including the development of sustainable food education programs for health professionals, the release of the world’s first planetary health diet in 2019, (12) and C40’s Good Food City Declaration which commits signatories to reduce carbon emissions and increase resilience of city food systems by working with citizens to adopt the Planetary Health diet by 2030. (13)

From Food Security to Food Justice Although social justice informed sustainable foodways thinking from the earliest days of the contemporary sustainable agriculture movement, critics both within and outside of the community food movement have long urged a deeper recognition of the inequities perpetuated by industrial foodways. These voices encouraged the community food movement to put more emphasis on the well-being of all the people that work to feed us-particularly farm and food system workers-in rural communities and communities of color. These harms of the global industrial food system are rooted in historical patterns of access to and exclusion from resources based on race, class and gender that shape our relationships to land, people and community to this day. (14)

These voices urge us to acknowledge that the global industrial food system rests on a foundation of colonial thinking that justified genocide, theft, rape, murder, slavery, racism and oppression to support the good life of an elite class of Europeans. This legacy of colonialism is kept alive this day by our willingness to eat from a food system that requires farm families to subsidize farm income with off-farm employment, depends on people of color to labor in working conditions that are not tolerated by white U.S. workers and perpetuates the fragility of our nation by fueling agricultural injustice, food insecurity, degenerative disease and climate change.

Who is included in community, where does it begin and end, and who does the community food movement serve? These questions invite us all to reflect on both the intent and that has been dominated by progressive, white, middle-class leaders who have failed to recognize the inadequacies of a change strategy focused primarily on market-based solutions to the harms of industrial food.

Market-based strategies have yielded some sustainability benefits, such as increased food literacy, more direct market opportunities for producers and more diversified food purchasing options for recipients of federal, state and community-based nutritional assistance programs. As demonstrated during the early days of the COVID pandemic, these strategies have also cultivated local and regional food networks that increase the functional and response diversity of our national food system. These benefits are welcome and important, but upon closer examination, it is clear that the primary beneficiaries of nearly half a century of sustainable food activism are progressive white middle- and upper-class eaters and the businesses that cater to them. Although the intent of the good food movement may have been food system transformation, the effect has been to protect the existing industrial system through economic development that tends to reinforce existing race, class and gender inequities.

This critique of the sustainable food movement has been recognized in the U.S. as a call for “food justice” through the different, but related, food sovereignty, food democracy, food solidarity and fair trade movements. Integrating lessons learned in the social justice and environmental justice movements, the food justice movement supports work led by Indigenous peoples and people of color to confront the structural inequities in the food system. This work emphasizes food system relationships—those that harm, those that heal and those that have the power to cultivate cooperation, trust and sharing economies that promote the health and well-being of land, people and community.

The Growing Food and Justice for All Initiative (GFJI) is just one example of the many organizations working towards the just transformation of community foodways. Launched in 2008, the Initiative promotes food justice in the tradition of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Beloved Community.” Working to dismantle racism and empower low-income communities and communities of color through sustainable and local agriculture, the GFJI shifts the role of immigrants, Indigenous peoples and other communities of color from laborers to entrepreneurs.

According to Erica Allen, co-founder of the GFJI, (15) the goal of the Initiative is to empower and challenge people to do the work of removing the obstacles of racism and the other “isms” that stand between all people and a fair and equitable food system. GFJI members lead research, policy-making and projects that advance the organization’s anti racist and economic objectives through community formation, political activism and the identification of effective strategies for leveraging food-based economic development.

The members of GFJI and other food justice organizations invite us all to reconsider the contradictions in our own ways of thinking about food-history, core concepts, values and practices—in order to find new ground for collaborative actions that disrupt the colonial roots of global industrial foodways. Over the last decade, the Initiative has nurtured the development of new food justice organizations led by Blacks, Indigenous people and people of color as well as continuing to work with other community food organizations to more fully integrate antiracist values and goals into their work.

One measure of the success of the food justice movement is the growing recognition within U.S. sustainable agriculture and food organizations of the need to promote racial healing and anti-racism practices within their own organizations. Amplified by the many inequities in the U.S. food system revealed by the COVID pandemic, (16) this new awareness prompted the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition to declare, “There is no future for sustainable food or farming without racial justice.” (17)

Some of the 45 farmers and ranchers who share their stories in Resilient Agriculture: Cultivating Food Systems for a Changing Climate, 2nd Edition and a companion website, RealWorldResilience.org.

Some of the 45 farmers and ranchers who share their stories in Resilient Agriculture: Cultivating Food Systems for a Changing Climate, 2nd Edition and a companion website, RealWorldResilience.org.

Notes

- Congress created a useful legal definition of sustainable agriculture in the Food, Agriculture, Conservation and Trade Act of 1990. This definition explicitly acknowledges the multiple dimensions of sustainability — ecological, social and economic — and provides a general description of the purpose of sustainable agriculture and some desirable qualities and behaviors: “The term sustainable agriculture means an integrated system of plant and animal production practices having a site-specific application that will, over the long term: satisfy human food and fiber needs; enhance the environmental quality and the natural resource base upon which the agricultural economy depends; make the most efficient use of nonrenewable resources and on-farm resources and integrate, where appropriate, natural biological cycles and controls; sustain the economic viability of farm operations; enhance the quality of life for farmers and society as a whole.”

- This discussion of pastoral, horticultural and sedentary agriculture foodways was adapted from E. Schusky, Culture and Agriculture: An Ecological Introduction to Traditional and Modern Farming Systems, Greenwood Press, 1989.

- In 1987, the United Nations Brundtland Commission defined sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

- For example, Wes Jackson, New Roots for Agriculture, University of Nebraska Press, 1980; Sustainable Food Systems, 1983; Joan Gussow and Kate Clancy, “Dietary Guidelines for Sustainability,” Journal of Nutrition Education, 1986; Brewster Kneen, From Land to Mouth: Understanding the Food System, 2nd Edition, 1995; Jack Kloppenburg et al., “Coming Into the Foodshed,” Agriculture and Human Values, 1996; Brian Halweil and Thomas Prugh, “Homegrown: The Case for Local Food in a Global Market,” Worldwatch, 2002.

- According to the Regenerative Agriculture Alliance, decolonization is about restructuring the systems that currently are responsible for the destruction and degeneration of life on earth, while validating such actions in the name of progress and civilization. Decolonization is a process intended to transform ownership, control and governing structures currently responsible for the destruction of natural systems, expropriation of ancient native lands, the invalidation of farming, governing, and commons-based systems that promote a symbiotic relationship with nature, and the continued war against Indigenous-centered cultures. See “Regenerative Agriculture: A Decolonization and Indigenization Framework,” Regenerative Agriculture Alliance. 2020.

- For example, the Real Food Challenge was founded in response to growing movements for farmworker justice, international fair trade, student farms and gardens, and local food as a means to amplify student voices and focus collective efforts on real change in the food industry. The National Good Food Network promotes market-based solutions in food distribution that will bring more food from sustainable sources to more people and places. The American Planning Association was a key partner in Growing Food Connections, an effort to build local government capacity to enhance food security for all.

- For example, Branden Born and Mark Purcell, “Avoiding the Local Trap Scale and Food Systems in Planning Research,” Journal of Planning Education and Research, 2006; Holly Hill, “Food Miles: Background and Marketing,” ATTRA, National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service, 2008; John Ikerd, “Reclaiming the Heart and Soul of Organics,” in Sustaining People Through Agriculture Series, 2008; Christian Peters et al., “Foodshed analysis and its relevance to sustainability,” Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 2009; Josee Johnston et al., “Lost in the Supermarket: The Corporate-Organic Foodscape and the Struggle for Food Democracy,” Antipode, 2009; Laura DeLind, “Are local food and the local food movement taking us where we want to go? Or are we hitching our wagons to the wrong stars?” Agriculture and Human Values, 2010; Allison Perrett and Charlie Jackson, “Beyond Efficiency – Reflections from the Field on the Future of the Local Food Movement,” Vermont Food Systems Summit, 2013; Carrie Furman et al., “Growing food, growing a movement: climate adaptation and civic agriculture in the southeastern United States.” Agriculture and Human Values, 2013.

- Joan Gussow and Kate Clancy, “Dietary Guidelines for Sustainability,” Journal of Nutrition Education, 1986.

- Joan Gussow, “Dietary Guidelines for Sustainability: Twelve Years Later,” Journal of Nutrition Education, 1999.

- “Principles of a Healthy, Sustainable Food System,” American Planning Association, 2010.

- For example, ChelseaCanavan et al., “Sustainable food systems for optimal planetary health,” Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 2017.

- Walter Willett et al., “Food in The Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets From Sustainable Food Systems,” The Lancet, 2019.

- Around the world, C40 Cities connects 97 of the world’s greatest cities to take bold climate action, leading the way towards a healthier and more sustainable future. Building on the work of the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, the C40 Food Systems Network supports city-wide efforts to create and implement integrated food policies that reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, increase resilience and deliver health outcomes. www.c40.org

- For example, Charlotte Glennie and Alison Alkon, “Food Justice: Cultivating the Field,” Environmental Research Letters, 2018; Leah Penniman, “4 Not-So-Easy-Ways to Dismantle Racism in the Food System, Yes Magazine, April 2017; Rachel Slocum et al., “Solidarity, space, and race: toward geographies of agrifood justice,” Spatial Justice, 2016; Julian Agyeman and Jesse McEntee, “Moving the Field of Food Justice Forward Through the Lens of Urban Political Ecology,” Geography Compass, 2014; Alfonso Morales, “Growing Food and Justice: Dismantling Racism Through Sustainable Food Systems,” in Cultivating Food Justice: Race, Class and Sustainability, 2011; Patricia Allen, “Realizing Justice in Local Food Systems,” Cambridge Journal of Regional Economy and Society, 2010.

- The Urban Growers Collective is a Black- and women-led nonprofit farm in Chicago, Illinois, working to build a more just and equitable local food system. The collective cultivates eight urban farms on 11 acres of land, predominantly located on Chicago’s South Side. These farms are production oriented but also offer opportunities for staff-led education, training and leadership development. The Growing Food Justice Initiative is a program of the Collective. urbangrowerscollective.org

- For example, see this special issue of the Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems and Community Development: “The Impact of COVID-19 on the Food System,” 2021; and coverage by popular media: Michael Corkery and David Yaffe-Bellany, “U.S. Food Supply Chain Is Strained as Virus Spreads,” New York Times, April 13, 2020; Jill Colvin, “Trump orders meat processing plants to remain open,” AP News, April 28, 2020; Victoria Knight, “Without Federal Protections, Farm Workers Risk Coronavirus Infection To Harvest Crops,” National Public Radio, August 8, 2020; Brooke Jarvis, “The Scramble to Pluck 24 Billion Cherries in Eight Weeks,” New York Times Magazine, August 12, 2020.

- “There is No Future for Sustainable Farming Without Racial Justice,” National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, June 2020.