This article was originally published on Waging Nonviolence

Since Russia started its war on Ukraine, we’ve seen a tremendous outpouring of solidarity with Ukrainians. People have made online donations to the Ukrainian army, Europe has welcomed refugees with open arms and free trains, western countries have united in their imposition of sanctions on Russia and discussed ridding themselves of its oil and gas.

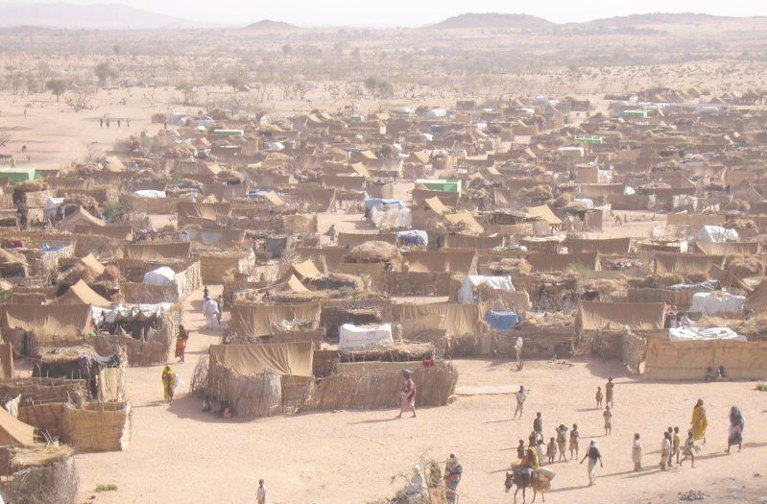

Such support is truly unprecedented. Can you imagine mass donations to the armed resistance of another group of people under attack, like the Palestinians? They would immediately be called a terrorist. Meanwhile, Europeans helping refugees from Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan, Libya, and elsewhere are accused of human trafficking. There’s also no head of state daring enough to denounce the genocide of the Uyghurs by China, nor any government refusing to buy Saudi oil in protest of the war on Yemen.

This is why some have argued that the war on Ukraine is exposing the global North’s blindspots, double standards and outright racism. In short, our solidarity seems to be conditioned on the affected people being white and Christian.

Yet, by focusing on these double standards, we’re missing an important strategic dimension: Precedents like this outpouring of Ukrainian support and solidarity are one of the most powerful ways to create change. As unfair as it may seem, welcoming the precedent and showing that it is possible to break with business as usual — rather than only denouncing the blindspots — is a first step toward making the precedent the new normal.

Breaking with business as usual

Social movements — or any organized effort towards social transformation and collective emancipation — usually have three different goals. First, they can aim to set precedents, open new possibilities and shift lines (ideally beyond just “the narrative”). Their role, here, is to achieve “cultural” change, ensuring the zeitgeist continues shaping that which appeared impossible, unnecessary, or unreasonable into what’s possible, necessary and reasonable.

Movements can also aim to turn these precedents (and any other demand) into the “new normal,” making sure the changes happening in people’s minds are turned into policies, norms, habits, etc.

Finally, movements can aim to fight against any backlash or attempt by the state or institutions to destroy something movements have achieved — like pensions or workers rights. These are called “defensive” struggles.

Over the past few weeks, we’ve seen the line between what’s unrealistic and what’s possible shift very rapidly. To name just a few examples, we’ve seen:

- refugees being genuinely welcomed, unconditionally

- the assets of billionaires frozen and seized, as well as unprecedented international cooperation to take control over the interests of Russian billionaires

- a “rogue” state disconnected from the global financial system

- states proactively divesting from fossil fuels

- an unprecedented sports, culture and economic boycott

- a giant shift in our energy system, with major countries genuinely considering the possibility of phasing out Russian oil and gas.

Interestingly, and somewhat counterintuitively, these shifts have not been the result of a big social mobilization. They actually came about before social movements were able to mainstream the aspirational demands that underlined them. For organizers and activists, this is surely an odd moment. What’s more, these shifts have come after two years of a global pandemic, during which we’ve seen states in the Global North do even more of what we were previously told was impossible. Things like:

- shifting billions to support public services

- relocalizing some strategic production sectors

- recognizing the importance of “frontline” workers, such as the role of health care professionals in our societies

- massive redistributive policies to support those who lost their jobs or income during the lockdown.

While none of these actions means wealthier countries are suddenly more caring and less racist, they do show that a future of care, solidarity and justice is possible — if only because the precedent has been set. Welcoming refugees and offering hospitality can no longer be called risky or unreasonable.

There are alternatives

It’s important for us to seize the moment and understand the full implications of this situation. We have a responsibility to extend these precedents — make them permanent, rather than temporary — and work to expand them so that all refugees are covered, not “just” the ones European or North American states are keen to welcome. Ultimately, these precedents need to be anchored by an emancipatory framework (i.e. no policing of borders, no repression of solidarity).

We can begin this process by supporting the precedents now being set. We should welcome the fact that states are opening the borders to Ukrainian refugees and make sure that this will apply to anyone forced to leave their country. Moreover, activists and organizers are no strangers to these changes. Only a few weeks ago, Poland was building a wall at its border, and migrants from Ukraine were not treated much better than any other migrant. If states have completely changed their approach, it’s surely because of the war — but also because there was a broad cultural consensus to support the victims of the war. We could, and should, celebrate this as a success for those fighting for the freedom of movement and against the policing of borders.

Rather than argue over how differently some of us are supporting people based on where they come from, we should argue over the strategies needed to move from “Ukrainian refugees welcome” to “all refugees welcome” and “freedom of movement.” How can we make sure that the war on Ukraine will not only lead us toward an actual phase out from Russian coal, gas and oil, but from all fossil fuels more generally, wherever they’re extracted?

The latest developments have proven — loud and clear — that the lack of ambition, the absence of policies of solidarity and hospitality, can be overcome. The ongoing solidarity with Ukrainian refugees reveals not only the existence of double standards, but the lies of our world leaders. Decisions to support the Ukrainian people and target Russian interests show that anyone saying “there’s no alternative,” “we can’t welcome all refugees,” “we can’t tax billionaires because it’s too complex” or “it’s not possible to divest from fossil fuels” is actually lying, for the sake of defending their own personal interests.

We’ve seen that there are, in fact, alternatives — and that another world is, indeed, possible. It is only a matter of political will. We can turn concrete acts of solidarity into the new norm so that there might, eventually, be hope in the dark.

By Mark Knobil from Pittsburgh, usa – Camp, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2173345