For roughly a decade, the U.S. oil industry and its backers touted American oil abundance and “energy dominance.” But in the face of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and resulting sanctions, gasoline prices immediately spiked 79 cents a gallon in the span of two weeks, briefly touching a record high of $4.43 a gallon and the market’s been in turmoil ever since.

Domestic oil drillers have proved unable or unwilling to offer drivers rapid relief, with one oil executive warning that shale companies were already struggling and would not be able to increase production. Indeed, weekly crude oil production in the United States hovered at 11.6 million barrels a day through February and into mid-March, federal data shows — down from pre-pandemic heights of over 13 million.

The pain at the pump for American drivers has roots that run deeper than today’s crisis. In recent years, while fracking’s supporters were shouting “drill baby drill” the oil industry began lobbying behind the scenes to undercut programs designed to make vehicles more fuel efficient or less reliant on fossil fuels. Alongside automakers, they helped pave the way for a boom in gas guzzlers that attracted consumers when gas prices were relatively low: In 2021, a stunning 78 percent of new vehicles sold in the United States were SUVs or trucks, according to the Wall Street Journal. American carmakers like Ford, General Motors, and Fiat Chrysler have nearly abandoned making sedans for U.S. drivers altogether.

That was a step in the wrong direction, efficiency advocates say.

“We absolutely should be moving to establishing independence from fossil fuels, both for geopolitical and for public health and climate reasons,” said Luke Tonachel, director of the Natural Resources Defense Council’s (NRDC) clean vehicles and fuels group. “I think our best tool to fight petro-dictators is to shake off the need for the petroleum that is the source of their power.”

The recent bigger-is-better boom is creating big problems for drivers as gas prices soar because once a vehicle is built, keeping up with maintenance and deploying a few tips and tricks are about all your average driver can do to improve a car’s fuel efficiency beyond its design specs. Until today’s cars are retired, American drivers are pretty much stuck with hundreds of millions of vehicles built while gas prices largely hovered between $2 and $3 a gallon.

But while conversations about fuel efficiency are often dominated by debates about whether buyers or sellers should shoulder the blame for the stampede towards SUVs over Priuses, there’s another often-ignored actor in the room.

Federal rules shape the menu of options offered to consumers by requiring automakers to achieve fleet-wide averages on fuel efficiency. A quick look back shows the oil industry’s fingerprints (alongside those of car manufacturers) on gambits to grind down those fuel efficiency standards, leaving everyday Americans more dependent on oil.

“Least Efficient Globally”

This isn’t the first time Americans have been burned by vehicles that fail to deliver good mileage — nor that foreign governments sought to leverage that inefficiency against American drivers. In fact, today’s fuel efficiency framework was born in response to another oil supply crunch with geopolitical roots almost 50 years ago.

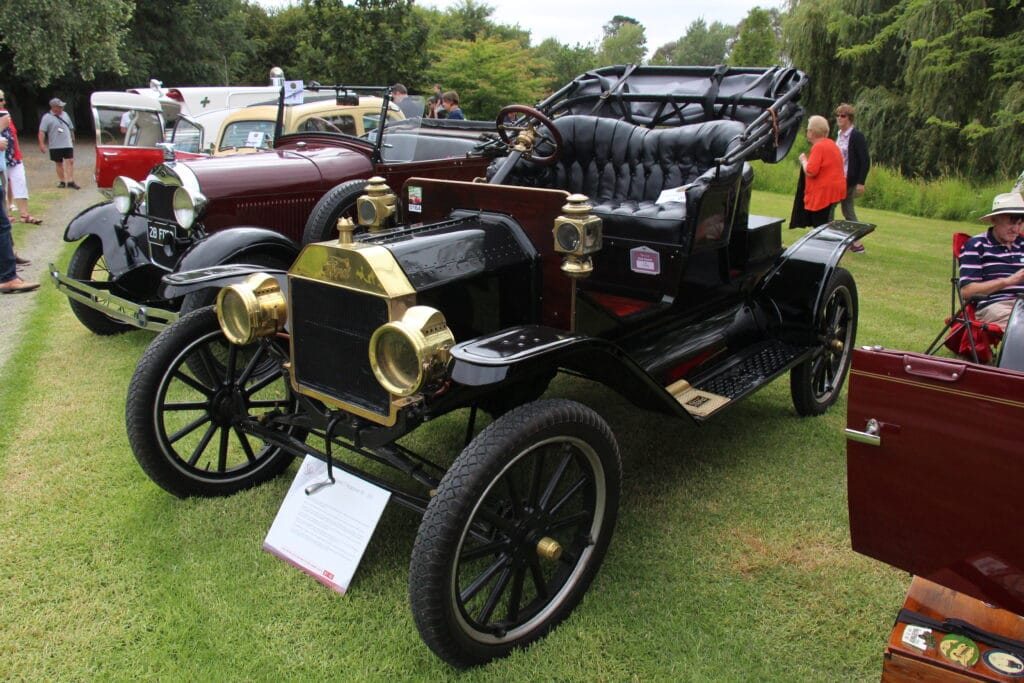

In 1973 the average gas mileage of new American cars had plummeted to an all-time low of 12.9 miles per gallon (MPG) — or about half the Ford Model T’s 25 MPG, according to The Atlantic. That same year, the first major oil crisis hit the United States in the form of an oil embargo by OPEC. As the Nixon administration scrambled to respond, oil rationing soon followed.

In response, the federal government created the Corporate Average Fuel Economy standards, or CAFE standards, designed to push automakers to make increasingly efficient cars by raising fleet-wide minimum requirements every year.

At 25 miles per gallon, Ford’s Model T had nearly double the gas mileage of the average new American car in 1973. Credit: Sicnag (CC BY 2.0)

That push worked for about the first decade. From 1975 to 1987, average fuel economy rose quickly — but then it declined between 1988 and 2004, as the Energy Department reported last year.

Average fuel economy rose again, by 29 percent between 2005 and 2020, the Energy Department added. But a closer look suggests that by other measures, efforts to improve the average gas mileage of all the cars, SUVs, and light trucks driving America’s streets slowed to a crawl in recent years despite technological leaps and bounds in hybrid and electric vehicles.

“Even as standards have tightened over time, the actual sales-adjusted fuel economy rating of new vehicles has been unchanged at around 25 miles per gallon since 2014,” the Wall Street Journal reported in January. “No wonder U.S. vehicles are among the least efficient globally.”

A November 2021 Environmental Protection Agency report touts the climb in fuel efficiency in 2020, noting a 0.5 mile-per-gallon gain to 25.4 MPG, “a record high.” But efficiency advocates noted those numbers actually fell short of federal targets, faulting loopholes in the law that they say promote larger vehicles.

“We’re facing a climate crisis, yet automakers are producing cars that are barely more fuel efficient on average than what they sold a year earlier, even as technology improves,” Avi Mersky, senior transportation researcher for the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, said in a statement that month. “They’re following the letter of the standards but exploiting all the weaknesses in the regulation to keep making gas guzzlers. It’s terrible for the climate and it costs drivers at the pump, especially now as gas prices are increasing.”

Fighting Fuel Economy

Battles over fuel efficiency standards most recently came to a head as the Trump administration considered unwinding Obama-era rules that would have pushed CAFE standards to 50 MPG by 2025 (with the caveat that, because of the law’s quirks, real world gas mileage differs from the CAFE numbers).

“The auto industry has really been the main fighter [against] improvements to the CAFE standards,” Dan Becker, director of the Center for Biological Diversity’s Safe Climate Transport Campaign, said, describing lobbying fights stretching back decades. The oil industry, he said, had seemed to stay mostly on the sidelines. “I think the reason was there was enough of a market for oil that even if the U.S. demand was down somewhat, the oil majors would find plenty of people to buy their oil.”

But, he added, as President Trump entered office, some oil refiners also began to involve themselves in fighting auto efficiency regulations. In 2018, the New York Times uncovered lobbying efforts by oil companies and the Koch network.

“The oil industry’s campaign, the details of which have not been previously reported, illuminates why the rollbacks have gone further than the more modest changes automakers originally lobbied for,” the New York Times reported, describing fuel economy lobbying by the nation’s largest oil refiner, Marathon Petroleum, and by oil trade groups.

“‘With oil scarcity no longer a concern,’ Americans should be given a ‘choice in vehicles that best fit their needs,’ read a draft of a letter that Marathon helped to circulate to members of Congress,” the Times found. “Nineteen lawmakers from the delegations of Indiana, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania sent letters to the Transportation Department that included exact phrases and reasoning from the industry letter.”

A number of organizations with ties to the Koch network also joined in lobbying to weaken clean car standards, as DeSmog previously reported. In March 2018, representatives from 11 groups, including the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI), the 60 Plus Association, Frontiers of Freedom, and the Taxpayers Protection Alliance (TPA) asked EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt to prevent California from setting its own fuel efficiency standards.

Koch Industries itself, the Times found, even lobbied to repeal CAFE standards entirely.

The subsequent Trump rollbacks (which reduced plans for fleetwide averages to hit roughly 55 MPG by 2025 to about 40 MPG by 2026) had significant impacts, said Tonachel. “It was a huge setback in terms of the innovation signal to the market and the opportunity for consumers to have access to cleaner, more efficient vehicles,” he said. “It cost consumers money at the pump as well as putting us in reverse in terms of addressing climate change.”

Over the past year, the Biden administration began unwinding moves made by President Trump to loosen fuel economy standards. “We’re now headed back in the right direction,” said Tonachel, adding that the administration’s goal of having 50 percent of car sales be zero emission vehicles by 2030 is “actually the minimum of what we should be doing.”

Nonetheless, the Trump-era rollbacks have continued to echo. Not only did they impact cars on the road today, Becker noted, they were also used by auto lobbyists to argue for weaker standards in California, whose authority to regulate car emissions was recently restored.

The notion of oil abundance was never a good reason to loosen fuel standards, efficiency advocates said.

“Even if there’s an abundance of fossil fuels, if we burn it, we’re burning the planet,” Tonachel said. “There’s no basis to burn more of it when we’re in a climate crisis.”

Electrifying the Future

Gas prices, of course, deeply affect the ways that potential car buyers think about fuel efficiency. A widely cited 2018 report by Cox Automotive highlighted $4 a gallon as a “tipping point” for consumer demand for hybrids and sedans.

These days, fuel efficient vehicles and EVs are increasingly catching buyers’ eyes (though some fear supply chain issues may make transitioning today harder than it would have been yesterday). Demand for Ford’s F150 Lightning EV pickup truck, for example, has vastly outstripped supplies; there is approximately a three-year wait for the vehicle, trade publication Equipment World reported on March 14. “With more than 200,000 reservations by December, the company announced plans in January to double production of the electric trucks as reservations were cut off.”

A poll by Consumer Reports last year found that 89 percent of U.S. drivers supported improving fuel efficiency for pickup trucks, SUVs, and other vehicles. “Car buyers expect new vehicles to be more fuel efficient, but automakers are failing to deliver what their customers want,” David Friedman, Consumer Reports’ VP of advocacy, said as that poll was released.

But as lawmakers consider ways to reduce oil dependence following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February, some Koch-linked organizations have re-entered the fray. On March 8, Tom Pyle, president of the Institute for Energy Research, also linked to Koch, testified at a congressional hearing on electric vehicles, faulting the concept of an energy transition for higher prices.

“A significant part of our current problem is the endless repetition of the propaganda about the utility of alternative sources of energy, the possibility of net zero greenhouse gas emissions, and the inevitability of an ‘energy transition,’’’ Pyle said. “These foundational myths have led directly to higher energy prices for Americans.”

Biden should realize that California is not a panacea for the rest of America that does not have similar goals and needs and does not want to be burdened with the high energy prices that his policies are producing as evidenced by the California experience. https://t.co/YJMguXqSVU

— Institute for Energy Research (@IERenergy) March 17, 2022

Americans for Prosperity (co-founded by David Koch) has also sought to shift some of the blame for rising gasoline prices away from the invasion of Ukraine and onto the Biden administration’s climate policies.

“The price at the pump and for home expenses began to rise before the Russian invasion of Ukraine,” a post by AFP updated on March 7 says before launching into a list of ways it alleges the Biden administration “affected gas prices, home heating costs and other energy-related burdens U.S. families and businesses face” (with no mention of the oil and gas industry’s own financial failures that drove investors away). First on AFP’s list is the EPA’s regulation of methane emissions — a major contributor to climate change.

Of course, fuel inefficiency has significant climate impacts. The EPA now ranks the transportation sector as the top contributor to U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, with light-duty vehicles responsible for the majority of those emissions. Becker called the push for efficiency “drilling for oil under Detroit” rather than Texas, saying it offered major climate benefits.

“The biggest single step we can take to cut our dependence on oil and to stop global warming is to make vehicles efficient,” said Becker, “and ultimately, they need to be electric.”