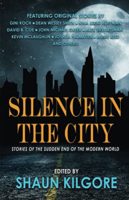

Silence in the City: Stories of the Sudden End of the Modern World

Silence in the City: Stories of the Sudden End of the Modern World

Edited by Shaun Kilgore

237 pp. Founders House Publishing, Jan. 2022.

Paperback, $15.99; eBook edition, $5.99.

Last year, author and publisher Shaun Kilgore put out a call for stories for a new fiction anthology. The prompt was to write a tale in which life in a modern industrial city grinds to a halt due to a sudden disruption to its power supply. Beyond that basic setup, the creative field was wide open, with the genre, setting, tone and other story elements left completely up to each author. Kilgore’s goal was to assemble an eclectic mix of stories exploring their shared premise from as many angles as possible.

The resulting book, Silence in the City, certainly achieves that mix. Genre-wise, its stories span the full spectrum of speculative fiction, from comic fantasy to grounded science fiction to psychological horror. They’re equally varied in tone and thematic ambition: Whether you’re looking for pure silly diversion, insights into the human condition or practical ideas on how to survive without electricity, you’ll find something to like here. Though the stories’ quality ranges from fair to excellent, even the weakest entries held my interest all the way through.

The collection opens with a pair of delightfully loopy fantasy comedies, beginning with Alex Shvartsman’s “A Dark and Stormy Night.” The protagonist of this first tale is part of a New York City neighborhood crime watch specializing in paranormal threats. The story begins with the city suddenly losing all its power and all its magic. In order to defeat the culprit—a malevolent mythological sea giant with an army of warrior-dolphins and walrus-sorcerers—our hero must ally himself with such unsavory characters as vampires, warlocks, snake-headed monsters, yeti and were-jackals.

The second comic fantasy, “Boston Falls” by Kevin McLaughlin, is told from the perspective of an off-duty hospital nurse. When Boston is beset simultaneously by a power outage and hordes of rampaging orcs, zombies and dog-sized spiders, our nurse leaps into action to tend to the wounded. Despite its overall goofiness, this story does have meaningful things to say about industrial society’s reliance on electricity. The hero reflects, for instance, on all the hospital patients who are likely to perish because of their dependence on machines requiring electricity.

Another fantasy piece, Annie Reed’s “The Unicorn,” goes for wonder rather than laughter. This one is set in the apartment of a young Manhattanite couple named Barb and Lexi during a massive blackout. As the blackout stretches from hours to days, Barb and Lexi are greeted each night by the awesome sight of a living, breathing unicorn in their patio vegetable garden. How are their fates tied to that of this magical animal? The scenario is as poignant as it is unlikely.

John Michael Greer’s “The Day of the Reaping” is the story of a middle school-aged boy named Josh, who learns his city is about to be “reaped,” or permanently cut off from the electric grid. Josh inhabits a future in which America is slowly being de-electrified due to the steady depletion of the energy resources that feed the electric grid. He’s a bright kid who sees through the mass media propaganda insisting that there’s no cause for concern about the city’s future power supply. His mother, however, believes the propaganda. Can Josh shake his mother out of her trance and convince her to flee with him before life in this community becomes untenable? It’s a revealing conflict, deftly handled by Greer.

While a number of stories serve as parables on the value of traditional technologies and wisdom in times of crisis, there are two that do so especially pointedly. Joshua Palmatier’s “The Cloud” takes place aboard a cutting-edge space station just as the space station and Earth are about to be engulfed by an ominous interstellar cloud. As panicked crowds flee Earth for the perceived safety of the space station, our main characters are desperately trying to do the opposite, sensing the danger of relying on artificial life support systems that have no backups in the form of Earth’s living systems. Meanwhile, Kirsten Cross’ “In the land of the blind” has human talents and street smarts triumphing where modern technology—rendered useless by a massive solar flare—has failed in finding a family’s missing matriarch.

The threat in “The Darkening” by Gini Koch, writing as A.E. Stanton, is another solar flare, this time triggered by a colossal wave of stellar ejecta from a near-Earth supernova colliding with our sun. The year is 2724 and industrial technology has continued to advance unabated, as have its diminishing returns. Earth is so polluted that people are forced to live inside vast, self-sufficient domes, and the technology that caused this ruin is more vulnerable than ever to collapse at the hands of nature’s whims.

The premise of a modern city abruptly being cut off from its lifeblood is one that obviously lends itself well to horror scenarios, and thus each entry in this collection contains at least some horror elements. There are, however, a few pieces that are horror tales first and foremost. In two of these—D.B. Keele’s “Taking Chances” and D. A. D’Amico’s “Gloss”—the horror is psychological, stemming, respectively, from a terrifying period of confinement in the home of a sadistic kidnapper and a visceral glimpse into the hallucinatory world of a troubled mind. Supernatural horror is the focus of David B. Coe’s “Below,” in which a city’s suddenly darkened subway system becomes a portal into an enchanting but perilous otherworldly realm. And in Shaun Kilgore’s “A Previous Engagement,” horror takes the form of roller coaster thrills involving mayhem at an airport.

Nina Kiriki Hoffman’s “Girlfriend Experiences” and Dean Wesley Smith’s “Everything Got Colder” are a study in completely opposite endings. Hoffman’s story starts off grim but closes on an upbeat note for its heroine, a down-on-her-luck young woman for whom apocalypse provides a fresh start. Smith’s tale undergoes the opposite progression, moving from hopeful to bitterly ironic as it shows a father braving a brutal winter alone as he waits for the return of his missing family. Each ending is admirable in its own way.

I mentioned earlier that some stories are stronger than others. The weaker ones suffer from problems such as too much summary and not enough scene, overly ostentatious prose and excessive typos—but again, their underlying ideas are compelling. As for the best of the bunch, they’re absolutely on point in every aspect of their conception and execution.

Teaser photo credit: By Jen – Self-photographed, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8618038