Ed. note: This article first appeared on ARC2020.eu. ARC2020 is a platform for agri-food and rural actors working towards better food, farming, and rural policies for Europe.

An appalling war on Ukraine has manifold impacts. The direct human cost is immense and incalculable. The impacts on the world’s agri-food trade and commodity systems will be huge. The 4 F’s – fuel, feed, fertilizer and of course food are all heavily implicated. So what to do? Will Europe suspend progress on rerouting the food system towards more resilience, by doubling down into the worst aspects of these 4 F’s? Or can some aspects of a deeper iteration of food sovereignty emerge?

We at ARC feel deep empathy and support for the Ukrainian people. Their suffering is inconceivable – in cities as in villages. The exodus of millions fleeing the country, mainly women and children, is disastrous. The risks for a total war in Europe are immense. And the social, economical, environmental and geo-political consequences are incalculable.

We feel part of this tragedy as Europeans. And we want to shed light on our part of it. There is much to digest and respond to, as years seem to happen in weeks, but for now, we will focus on some farming, food and trade impacts of this war.

With exports of grain stopped from Ukraine, the vulnerability of the European and the global food system is apparent. Grain prices follow gas and oil heights, – so do fertilizers and pesticides. The first to suffer from this are food imports, economically dependent countries, many of them in Africa and the Middle East, already close to widespread hunger due to climate change, drought or floods. A new sanctions era compounds these price and availability stresses, from a human perspective, while also hitting the global economy hard.

The four F’s

source Trading Economics

The crucial roles both Ukraine and Russia play in global agri-food and related trade are hard to underestimate. They are core to feeds, fuels, fertilizer – with food, the end result of these, making 4F’s.

Russia is likely the world’s largest exporter of fertilizers, while as Hannah Richie has pointed out, when combined with Belarus, this is over ⅓ of all global fertilizer exports. Russia is also the world’s largest exporter of wheat.

Ukraine is the world’s largest exporter of sunflower oil, 4th largest exporter of corn, 5th largest exporter of wheat, supplying in particular the Middle East, Africa, and some Asian countries. 2/3rd of Egypt’s imports comes from Ukraine and Russia.

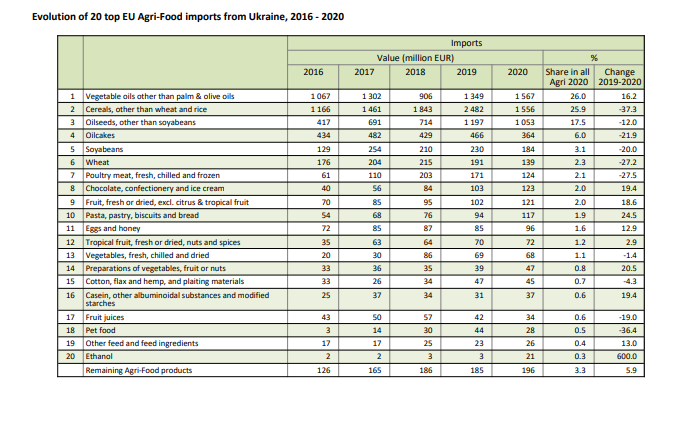

EU imports from Ukraine increased by over 50% in 2020-2021, indeed imports and exports have been increasing for a decade. The EU has a trade surplus of €4 billion with Ukraine – EU exports to Ukraine were €28 billion in 2021, while imports from Ukraine were €24 billion the same year. However the products themselves are noteworthy.

EU imports from Ukraine increased by over 50% in 2020-2021, indeed imports and exports have been increasing for a decade. The EU has a trade surplus of €4 billion with Ukraine – EU exports to Ukraine were €28 billion in 2021, while imports from Ukraine were €24 billion the same year. However the products themselves are noteworthy.

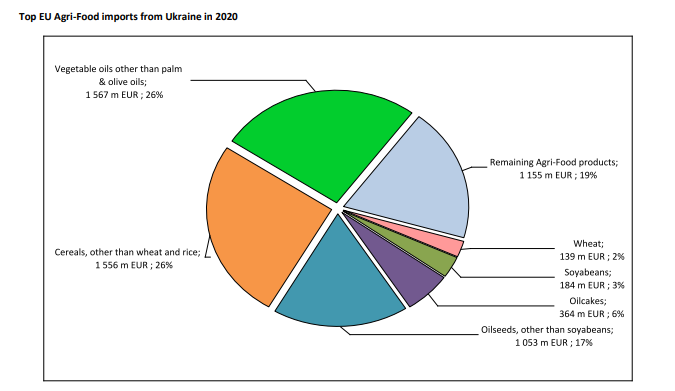

Within agri-food, for Europe, a range of oils, oilseeds, oil cakes and cereals make up the bulk of imports from Ukraine. Europe’s main export in this category is in fact tobacco products – cigarettes and cigars – followed by pet food, chocolate and confectionery. Source for charts and tables in this section – Agrifood-Ukraine_en

While Ukraine’s exports are now halted, and worryingly, farmers’ ability to plant cereals this Spring severely restricted, outflows from Russia are primarily limited to countries with sanctions imposed.

Europe and North America are embedded in an agri-food and global commodity trade system that is heavily reliant on fertilizers for grass and crop growth, fossil fuel (gas) for making this fertilizer, but also animal feeds and crops for biofuels.

The political response

On March 2nd Agriculture Ministers met to focus on the impact of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Member States requiring large amounts of imported feeds and fertilizers, and also exporting nations to Ukraine expressed concerns at the impacts. There were calls for market measures for livestock, the use of the Common Market Organisation (CMO) articles, extra flexibilities for seasonal and Ukrainian workers, and on the impact, including on the EU, of the severe shortage of grains in the Middle East and North Africa.

This crises – like the covid 19 crisis, and others before – have shown the importance of at least some degree of resilience, self-sufficient agri-food systems. The Farm 2 Fork strategy of the EU aims to reduce mineral fertilizer use by 50% by 2030, and would therefore make even more sense in this fraught context.

And yet, this is the very thing that is now under threat. The EU commissioner for agriculture, Janusz Wojciechowski has stated we need to “keep a close eye on the objectives of these policies in the context of food security” after the March 2nd meeting, a position he states is simply a reiteration of the general point of the 2020 communication on the EU Green Deal. However post meeting, the Commissioner did add that some elements of the Strategies (such as reduction of pesticides and antibiotics) are “political in nature,” are “not necessarily binding,” but are more “political message.” Certainly, the agri-lobby has seized the opportunity to question farm 2 fork. Under the guise of a very specific interpretation of food sovereignty, in France the National Federation of Farmers’ Unions (FNSEA) has issued a communique stating the “logic of degrowth desired by the European farm to fork strategy mush be deeply questioned”, while also critiquing the devotion of 4% of land to non-productive areas in CAP.

More short term considerations such as fallow land being used for protein crops for the 2022 growing season are now under consideration, following the meeting between European Agricultural minister and EU commissioner for agriculture, Janusz Wojciechowski on 2nd March.

Left-of-centre ideas are also emerging, such as compelling all farmers to grow at least some cereal crops, which have been heavily criticised as unrealistic by growers. Indeed many short term fixes could cause longer term problems – farmers have specialised, with some but by no means all able to grow cereal crops these days; machinery has become specialised too, with tiny portions in fields not the best for trying to grow crops commercially. And what will be lost with space for nature – and its pollinators – disappearing, and with the ploughing of permanent grasslands releasing carbon?

Crises is never a good time to make mid to long term policy. This emergency situation is further compounded by the fact that the cattle are in the fields. The monocultural spring grass is waiting for its fix of mineral Nitrogen, while Ukrainian farmers face extraordinary difficulties in planting and also exporting their crops. The specialist farm equipment and sheds are purchased, the agri-food trade systems are established.

Real Food Sovereignty – now is the time for Farm to Fork

source Our World in Data, Hannah Richie

It is interesting that the phrase food sovereignty is now in vogue at institutional and agri-industrial levels. Used repeatedly, but in a way that amounts to pan-continental resource use at the macro scale while maintaining high energy intensity products and systems. It is certainly not being used in the deeper sense of a regionalised resilience and solidarity economy as developed by La via Campesina and others from 2007 on. This shallow, business as usual version of food sovereignty presumes we can and should maintain what we produce and how we produce it. But is there a better way? Rather than a form of disaster capitalism exploiting a bad situation, can we have disaster solidarity? Can we both solidify what’s needed, continue the process of transition where appropriate, and show solidarity with our global friends?

So while a crisis is never a good time to make policy, what is produced, how and why? Critics of the EU moves away from environmental considerations have pointed out that the EU is already 112% self-sufficient in cereals and is already exporting over twice what it imports in cereals.

The probability that the crisis in Ukraine will affect food security in Europe is not doubtful. This can happen directly through the effects on the international trade of cereals and cereal price evolution and indirectly on the price of nitrogen fertilizers (linked to the gas price).

This should be an argument for accelerating the transition through an agriculture that does not rely so much on fossil fuel. It should be an argument for reintegrating quickly crop and livestock for maximising biological nitrogen fixation by legumes.

In other words, the F2F strategy implementation should be accelerated. – Alain Peeters (Vice-President of Agroecology Europe)

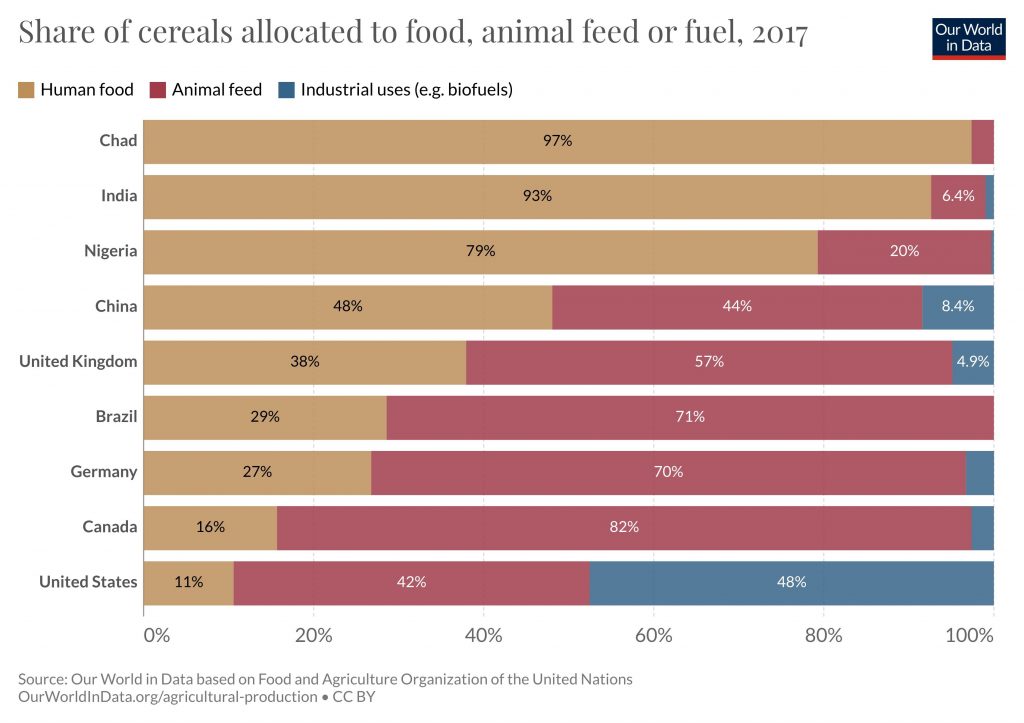

Others have pointed to where these crops go: crops are grown for biofuels and also as animal feeds. So these are often not for humans food, but for animals, with the milk and/or meat then fed to humans. Certainly the land and resource use of meat dairy and biofuel is significant, and all the more so in this new context of uncertain supplies of the core ingredients. So while there will be every effort made to continue these resource flows, what level that can be rerouted, or produced on farm or regionally, should be.

What we urgently need now to invest in is a new local and territorial infrastructure for food production and processing which transforms the agroindustrial food system into a resilient decentralized food supply system. The war in Ukraine reveals the extreme vulnerability of food supply, far from the food security of actual food sovereignty.

We’ve been here before

What level of restructuring of society is desirable, and possible, regarding transport, diet and other possibilities? Certainly, we have moved mountains before, from Covid distance-based restrictions and working from home, to car-free Sundays as a response to the oil crises in 1973 – which ushered in a cycling culture with us to this day in the Netherlands. The immediate adjustments to a war economy in places like the US were immense:

“From 1942 until 1945, the manufacture of cars was banned. So were new household appliances and even the construction of new homes. Tyres and gasoline were strictly rationed… A national speed limit of 35mph was imposed”.

Its worth remembering, that Dig for Victory was also about reducing metals used in the then popular tinned vegetables, to save them for the war effort.

But time is tight and we’re just coming out of a covid crisis. Timing is both with us and against us. It’s still early Spring, months from winter and with some fields – and extra spaces for urban horticulture and the like – potentially ready. However, orders have been made, plans too, and crops are set to go into certain places – into fields, onto ships and so on. Whatever happens, disruptions are inevitable.

And yet already, prices for the four F’s have been increasing since before the Russian invasion. Further reliance on the 4 F’s, in the quantities and for the uses currently planned, makes us even more dependent on them, and thus even more vulnerable.

Already, approaches like organic farming are chronically underfunded – as IFOAM EU analysis last week showed, even with the new CAP and the EU Green Deal. Organic farming, it is worth remembering, doesn’t use any mineral fertilisers and has legal limits on the amount of feed brought in. And while short term yield is an issue for some commodities, this is not the case for all of them – nor when investments and changes help narrow this gap. (More on organics here). Key here will be the legislation on OHMs – organic heterogeneous materials. Moreover, if yield is such a consideration, why produce for cars and animals rather than for humans?

What to do for now?

The conundrum is that more of these more agroecological and regionally resilient approaches would make Europe less dependent on four f’s – fuel, fertilizer, feed and food- but how to fast track this in yet another crises?

So when is the time? When is there not a crisis – climate, covid, conflict -? Some initial thoughts. More will emerge in the coming days from various sources.

- Maintain the General Escape Clause brought in with Covid-19. This suspends member state fiscal (debt and deficit) rules due to emergency. Use this mechanism to fund the following:

- Use the European grain reserve to feed people, including people in the Middle East and north Africa. The latter two regions will be especially hard hit by lack of grain for Ukraine. Everyone suffers in this context.

- Fast track food ombudsman in remaining member states to work on minimum and maximum prices, for the benefit of citizens and farmers.

- Start to fund the growing of crops (cereals beans etc) for human consumption – and concurrently reduce the quantities for pigs, poultry and biofuels. So instead of barley for pigs, grow wheat and legumes for humans. Compensate pig and poultry farmers for the financial loss.

- Public procurement and circular economy food waste mandates.

- Strategic food stock reserves in member states, aggregated for overall EU level.

- Farmers who can successfully grow feed crops for extensive livestock production, ideally integrated into mixed farming systems, should be incentivised to do so, especially in contexts where there are few negative environmental consequences.

- Incentivise more oil seed production in Europe for human consumption, not fuels, to compensate missing exports and to increase EU self sufficiency in oil seed

In all of this, our thoughts are with the people being bombed and displaced. There is suffering all over the world. The repercussions – the lives and towns destroyed, the people dislocated, will need our solidarity and support for quite some time. Food will be needed now for Ukranians and we will have to help rebuilding farming and infrastructure for a resilient Ukrainian food system. Beyond Ukraine, the repercussions will reverberate for years. We now have choices to make regarding (fossil) fuel, fertilizer, feed and food. We can maintain a downward spiral of dependency, still funding war machines and climate catastrophes, or we can, hard as it will be, build real solidarity via our own, deeper iteration of food sovereignty.

By User:Bluemoose – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=333105