Ed. note: This article first appeared on ARC2020.eu. ARC2020 is a platform for agri-food and rural actors working towards better food, farming, and rural policies for Europe.

For Xavier Hamon, the term ‘chef’ is problematic. It fosters an unfair power dynamic between the person who produces the food and the person who cooks the food. Yet farmers and cooks are often up against the same challenges. Xavier is a founding member of the Slow Food Cooks Alliance, a partner of Nos Campagnes en Résilience. He is also a cook, and university administrator. In his work, Xavier favours a cooperative rather than a competitive approach to food – to the benefit of all involved. In conversation with Valérie Geslin.

I grew up on my grandparents’ farm in Côtes d’Armor. I would have been happy to make my life there. But my family didn’t want me to be a farmer. I became a cook. In 1987 in catering college I was told nothing about farmers, the origin of the products, breeds, species of fish. But lots about the noble art of the chef as I learned techniques, gastronomy: all the prestige of cuisine and the French art de vivre. After working in several restaurants and for a host of different reasons (essential human ones – day-to-day abuse, insults, put-downs, competition and working conditions), I quit the industry.

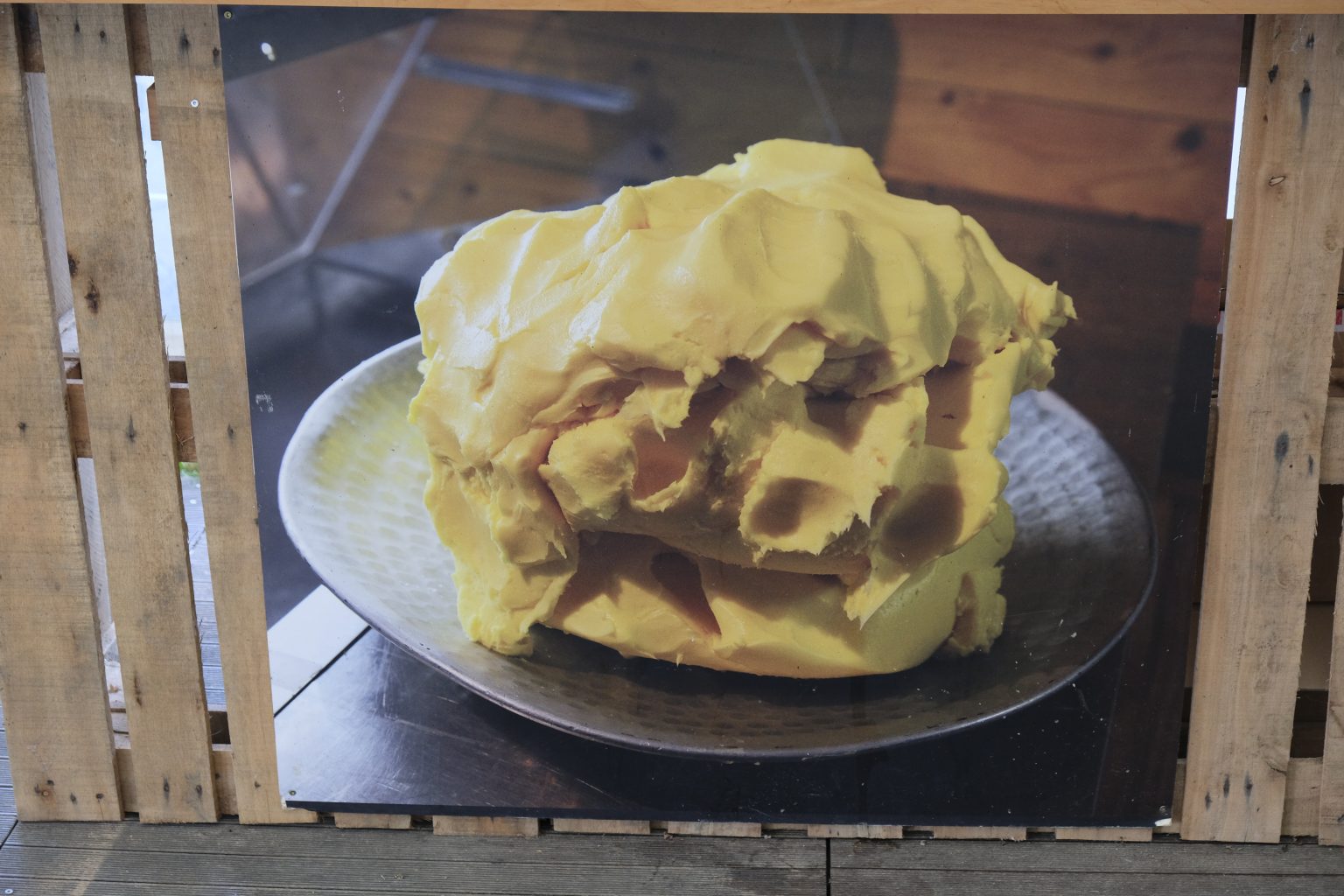

But after some time I came back to the restaurant trade. I started my own restaurant, with my own rules : I needed to know what I was putting on my plate, how it was made and who made it. Part of that is the people who process the food, the cheesemakers who have the know-how and can explain to me where it comes from and how, through their convictions, they make a tool of development of their own existence. I spent a lot of time with farmers and saw the natural ties between the job of a cook and a farmer, because as a cook I can contribute ideas on how to process and showcase their products.

My restaurant was in the centre of Brest in Brittany. I had an easy rapport with my customers – there was only a counter between us. What I told them was simple: when you come in here and have a meal for €17, behind that is the landscape, the environment, the breeds, the richness, my pleasure in my work. But also the people who can’t make a living from it – do you think that’s good enough? And as I told them that, I started to explore my own activity, my own direction. I was putting myself at risk by working and never discussing prices, by trying to pay people properly and make the meals accessible. I was earning €600 a month.

“I regret not teaming up with farmers”

Vegetable growers, livestock farmers, fishermen will tell you: “We chose this path because it’s the only path for our children.” Even if you can’t heat the house for your kids in winter. But this question of pay is evolving over time.

The hardest thing for me is that, until 2017, I didn’t manage to work with farmers. We worked in parallel. I regret not teaming up with the producers to run the restaurant together. I should have made the restaurant a cooperative: try to find an economy to make us stronger, how that added value can benefit everyone involved, rather than each person sending a bill to earn added value on each product. Put everything in common. There was definitely some experimenting to be done there.

Xavier Hamon animating an on-farm workshop at La Ferme des 7 Chemins, Brittany, September 2021. Photo credit: Hannes Lorenzen

The idealism of farming

I wanted to continue to reflect and work with farmers, so I started looking for political responses. I partly found them in the slow food movement, where I understood that me as a cook, I’d never get there by myself. But it was indeed a question of food, not a question of farming, that we all had to answer.

I started to decode what I call the idealism of farming: how you can get complacent in the corporatist culture, retreat into yourself on the pretext that it’s the only path possible to keep living by your morals. It’s about stereotypes, I often notice.

Historically, the added value came from the farm: the product was processed, sold, and all the added value came back to the farm. In fact there’s a whole branch of small-scale farming that says that those who process high-quality products are usurpers and are stealing the added value. They need cooks to take their know-how but they don’t want to get too involved with them.

For me there’s a corporatist, idealist connotation that gets in the way of political work on emancipation.

Slow food: it was indeed a question of food, not a question of farming, that we all had to answer. Photo credit: Hannes Lorenzen

University of gastronomy sciences and practices

The university ultimately crystallises what I’ve sown with friends over the years. It has several functions: training, research on topics that interest us around the profession of cook, for example: why is this profession so hopeless when it comes to working conditions, abuse… Cooks have been debating these topics for over a decade and nothing is changing. We need a new perspective. Sociologists and other social scientists are tackling that with us.

Another aspect is the ‘people’s university’: we go out and ask questions around town or on the village square. We discuss together, produce material from it and feedback.

In our training and in the people’s university, all the topics are decided with farmers I’ve been working with for 15 years. When I’m planning a module on plant-based cooking, for example, I bring to the table a vegetable grower, a seed producer, an agronomist, an engineer, a cook and an instructor. We build the content together: “What do you, as a farmer, want a cook to know?”

We end up with training modules I’d never have been able to create myself. When a vegetable grower tells me he wants the cook to know what it is to pull cabbages in February in the rain – we have to find a way to communicate that.

In conversation with Valérie Geslin. Translated by Louise Kelleher. This conversation has been edited for clarity.

In part 2 of this conversation, Xavier Hamon takes us further on his slow food journey, to discuss the fate of the Sustainable Food Consortium, and share his passion for his latest fair local food project – an on-farm restaurant.

Nos Campagnes En Résilience is ARC2020’s project to support and connect initiatives around rural resilience in France. Visit the project page here and follow us on Instagram, LinkedIn and Facebook. If you’d like to get involved, contact our project coordinator Valérie Geslin.

Teaser photo credit: Xavier Hamon (centre) with (L-R) Matteo Metta and Valérie Geslin of ARC2020, veterinary doctor and seed producer Sarah, and farmer and cheesemaker Cédric, at an on-farm workshop in Brittany, September 2021. Photo credit: Hannes Lorenzen