How do we develop vibrant local economies that are good not for the shareholders of a corporation headquartered in some distant state, but for the people who actually live in the neighborhood?

This is a crucial question for advocates building stronger, more resilient towns and cities. To help answer it, I recently interviewed Dave Kresta, an Adjunct Assistant Professor at Portland State University, where he teaches courses in the school of urban studies and planning.

With a background in computer engineering as well as an MBA, Kresta worked for years in the tech industry. As his job drew him more into business and strategy development, he began looking at deeper social issues, including poverty, gentrification, and the lack of affordable housing. “These are complex problems,” he said, “and from an intellectual perspective I was intrigued.”

Yet his interest was more than just academic. “I grew up with a strong faith as part of my upbringing,” he told me. “For the first part of my life, faith was more of a private thing, separate from what’s going on in the world around us.” But that was changing. Kresta felt called to help other people of faith understand the complex problems he was exploring, and then figure out how they can contribute to solving them. He returned to Portland State, earning a PhD in urban studies in 2019. His dissertation was on the impact of churches on neighborhood change, especially their economic impact.

In addition to teaching, Kresta is a Fellow at the Ormond Center at Duke Divinity School. As a consultant, he helps faith-based organizations partner with neighbors to build more vibrant, just, and equitable local economies. Last year, he released his first book, Jesus on Main Street: Good News through Community Economic Development.

In Part 1 of this interview, I talk to Kresta about the important differences between traditional economic development and Community Economic Development. We also touch on the role faith communities play in the local economic ecosystem.

In Part 2, to be published next week, Kresta and I talk about the practical ways faith communities can help build local economies, about gentrification, and about how (and why) to build bridges between faith communities and economic development leaders.

PATTISON

In your book, you are careful to differentiate Community Economic Development from traditional economic development. Let’s start with traditional economic development. Can you define or describe traditional economic development and also talk about where it falls short?

KRESTA

Sure. Traditional economic development is hard for most people to define, but you can see it all around you. Say you have a new corporate headquarters moving in. Amazon is the prime example. Pun intended, and I’d love it if you could quote me with that one.

PATTISON

That’s definitely going in the interview.

KRESTA

Amazon is the prime example of a company moving into a metropolitan area and everybody gets excited about new jobs and construction work and all that. But then you also hear some people pushing back against it. This is an example of the promise and then the dark side of traditional economic development. The promise is the top-level promise of more jobs, high paying jobs, growth overall for a community. The negative side—and this is where it falls short—is that it creates more demand for housing, driving prices up and displacing those who are not able to afford higher costs in their housing, whether it’s rent or mortgages. It also leads to increases in pollution, increases in congestion, drives out small businesses and caters to the big box retailers. Those come part-and-parcel with traditional economic development.

The other classic example is new or expanded freeways. They’re always couched in terms of how this is going to pave the way—pun not intended—for more economic growth. But guess what? The people get displaced whether it’s literally from their neighborhoods getting destroyed or further down the line with the increase that congestion brings and more demand for housing.

PATTISON

Let’s contrast that with Community Economic Development. What specifically is Community Economic Development? This, as a formal term, was new to me.

KRESTA

It’s actually been around a while. This is one reason I wrote the book, because I wanted to bring it to the front of people in the faith community.

Community Economic Development seeks to build long-term capacity in a community for equitable economic activity. Those are all key. There’s capacity, it’s long term and it’s equitable.

So examples of that include helping people to develop businesses, whether they’re microbusinesses or larger businesses, or workforce development programs, which help existing residents either get a job or grow into jobs that are coming into their neighborhood.

The focus is on the place and the people that live in the place. That’s really what distinguishes it from traditional economic development, which ostensibly is about the place but, really, is more interested in driving top-level economic output.

If you get an influx of highly paid white-collar workers and you displace the poor, that’s a win in traditional economic development because it drives top line growth and it looks like you’ve created a bunch of wealth in the community. For Community Economic Development, that’s not a win. That’s actually an utter disaster because the community itself is fractured. People are displaced. Existing residents are not able to participate in any of the economic increases that are resulting.

Dave Kresta’s book, Jesus on Main Street. (Source: Amazon.)

PATTISON

You write in the book that Community Economic Development has two goals: (1) Improve the economic situation of local residents and local businesses. (2) Enhance the community’s quality of life as a whole. In other words, Community Economic Development is local and holistic. I’d like to touch briefly on each of these. Why is the local aspect important?

KRESTA

Community Economic Development is by definition local. It recognizes that in most types of traditional economic development, the poor, the marginalized, those without power, and those without capital, are not really able to get ahead or participate in the economic bounty. Community Economic Development is local because it pays attention to the people that are already in that neighborhood or community. It’s better for the existing businesses and the people who are there, as opposed to bringing in from the outside a whole bunch of capital and investment and high paying jobs with an influx of new people.

PATTISON

Okay, same question about the holistic: Community Economic Development enhances the community’s overall quality of life.

KRESTA

A key indicator for traditional economic development activity is the total amount of tax revenue generated. As long as that’s going up and to the right, everybody’s happy. But thinking holistically about economic development in terms of quality of life means asking hard questions:

If we have more people moving into the neighborhood, what’s going to happen to the cost of housing? That needs to figure into the economic calculation.

Is money just being siphoned outside of the community and into corporate coffers? Or is the community able to keep the money and, with that money, maintain their houses, maintain streets, maintain the overall look and feel of the community?

Community Economic Development also recognizes that we’re not simply economic creatures. I mean, that’s one part of who we are and economics obviously has a huge impact on our overall quality of life, but it recognizes that that’s not the end of the story.

Can I add one more thing? Another critical element of this overall quality of life is self-determination and autonomy. Again, it’s not a win if you’ve got a top-down system that comes in and imposes economic growth on a neighborhood. It’s a win if the neighborhood can be autonomous to some degree, determining the answers to, “How do we want to use this street? What kind of businesses do we want in our neighborhood?”

A certain amount of collective action strengthens the overall dignity of people who live in a neighborhood. It recognizes their dignity and doesn’t just impose development on them.

PATTISON

Many people who are members of faith communities might be surprised to hear their congregation has a role to play in the economic development of the neighborhood. My hunch—and it’s just a hunch—is that many people who are involved in the day-in, day-out work of local economic development might be surprised to hear they could have an ally in a local faith community. How much work do you have to do to convince folks in both of those places that they can and maybe even should be working together?

KRESTA

On the faith-based side, I think there’s a growing recognition that we are called to care about our neighborhoods, to care about our communities. I think there is a growing recognition that faith communities do have an impact, either positive or negative. But I haven’t taken it upon myself to convince all the skeptics. I’m going for the low-hanging fruit. There’s enough who have come to the conclusion that, “Yes, we want to have a positive impact. Tell us more, how can we do this? How can we get beyond charity? How can we get beyond relief work and get involved in sustainable, long term development in our communities?”

So, I think that’s growing. On the economic developer side, I think there’s still a lot of work to do. People of faith have to earn their trust and show we have common goals, which is the thriving of our neighborhoods and our communities. I understand why some people have an aversion to faith-based groups. Maybe the onus is on us now to prove we can help and not be overbearing in our approach either.

I talk in the book about the economic ecosystems in our neighborhoods. If we’re going to move the needle on unemployment, or if we want to increase the economic multiplier and keep money circulating in your neighborhood, no one organization can do that. I’m trying to establish right up front that it takes an ecosystem. A church or faith-based group can fit into the ecosystem in a variety of possible ways, but they work with businesses and nonprofits and government and investors and developers.

Stay tuned next week for Part 2 of this interview!

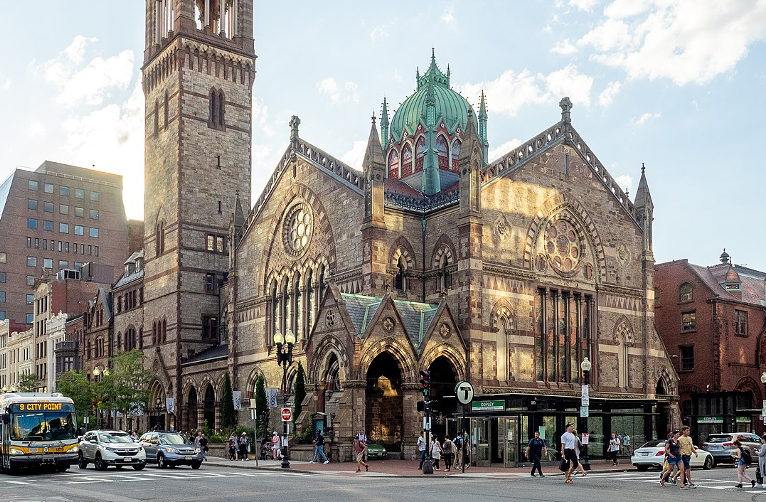

Teaser photo credit: By Ajay Suresh from New York, NY, USA – Boston – Arlington Street Church, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=82156221