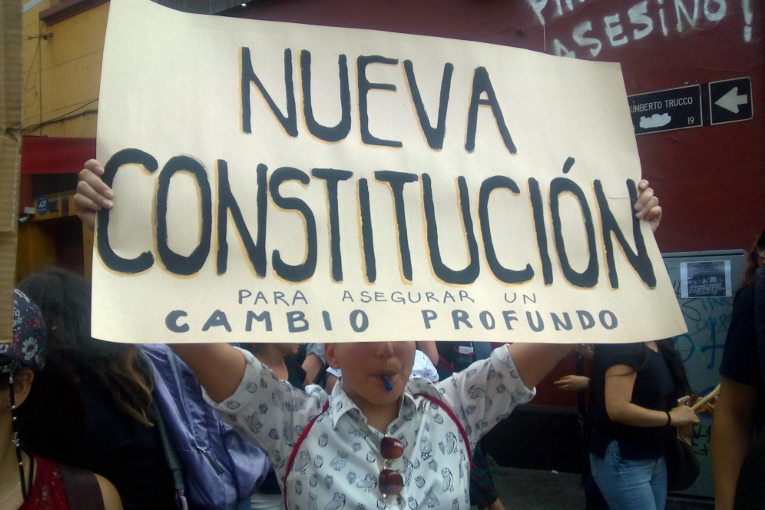

I come from Chile, a country in the Global South that is usually not at the center of the degrowth debate. Right now, a constitution is being drafted in an unprecedented, democratic Constituent Assembly, and a new progressive government has promised to address long-term inequalities. This is a moment of political creativity— an opportunity to challenge the boundaries of our imagination and reflect on the ‘common sense’ that has been handed down to us. Degrowth can open that door and help us question the larger superstitions that sustain our life today. My aim is to contribute to this particular political moment from a unique geopolitical perspective.

Deep, systemic, positive change arises when we collectively dream and enact a different form of society altogether — one focused on free and flourishing lives for all.

But this is sorely avoiding the heart of the issue.

Beyond an innocent bureaucratic tool, GDP has been an epistemic clutch for the developmentalist project that has dragged the whole of humanity into our current catastrophic state. What attracts me to degrowth as a political project is wanting to get rid of the supremacy of GDP for this wider cosmology to fall. Yes, we have built better indicators — the emblematic Human Development Index, for instance — but we have not seen these measurements significantly replacing GDP in its decision-making power.

Drawing from a more open political debate might help illuminate how different our conversations could be if we didn’t stop at the easy score of criticizing our measures of wealth and wellbeing.

Let’s talk about taxes. ‘Taxing the rich’ has become almost a truism: who could oppose it? If they are rich, surely they should be taxed. Rich people are even asking it themselves. US Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, only a few months ago, wore a dress saying exactly this sentence in a gala and got widespread applause for it. It seems like a shared flag of progressive movements worldwide. And, while still resisted by right-wing fundamentalists — that say that promoting more ‘entrepreneurship’ and ‘innovation’ are the best direct routes to improvement for all, and that taxes are an annoying inconvenience — the staggeringly high levels of income inequality virtually everywhere offer some common sense as a counterargument. Yet we could still tax the rich and lose. Don’t get me wrong, it is definitely something we should strive for on any given occasion. But wealth inequality is only one final loose thread of a fabric of oppressive relations. You can trim it and keep the weaving mostly intact. We tend to think of the problem of our societies in terms of inequality: some people have too much stuff, others have less. Taxing is a numerical way of balancing that. However, as anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow brilliantly argue in their book, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, a much more productive way to approach the fundamental questions of political life is by looking into what forms of freedom we have, not how ‘equal’ we are to each other. Why would we want to be ‘equal’ anyway?

What lies at the heart of the so-called inequality issue is that we have built our societies in a way that people with more money and property can boss around, and have life and death decision-making power over the vast majorities of overworked and exploited people. Climate change is an obvious, if only the most recent, example of this. This structure of domination, not inequality, is what we should aim to transform. If we instead address the deep-rooted structures and processes of exploitation — including racism and patriarchy — that allow that process of accumulation and shielding from democratic power in the first place, then taxing will be politically toothless.

A similar thing happens with GDP. The enshrining of this measure is a consequence, a visible symptom of a wider political, moral, ecological, and cosmological arrangements that have condensed in what we tend to limit as an economic order in a reductive sense. The political and administrative structures and processes of our societies — the global bureaucratic geopolitical order that underpins our horizons of possibility — rely critically on the constant expansion of work, material and energy use, and generation of waste. The uncomfortable truth is that this, while benefiting the big players (corporations, and the global rich minority that, as we know, produces 50 percent of global carbon emissions) has made us all hostage to the growth economy. Today, governments in poorer countries, the disadvantaged and exploited people in all countries, and virtually everyone that is not comfortably middle class, really, have their hopes and expectations for a better life firmly in the terrain of our carcinogenic economic engine.

We all want to get to that top 10 percent — we have learned that is the only good life humanity can collectively build. But a wellbeing based on endless consumption and the sacralization of work is one that simply cannot keep a planet inhabitable. We fear our national states will fail if we stop growing. We are fear-mongered into submitting to austerity measures because, if economic growth were to come to a halt, forget about any chance of ever getting anything nice from public institutions. And to some extent, this is true. But it is true not for some fundamental ‘expansive nature’ of humans that forces us to grow or die as an instinct as natural as salivating when thinking of food.

The political economy of our nation-state system was built with the supposition of growth at its centre, ignoring all we know and have conquered today in struggles for emancipation and self-determination that reveals the coloniality and ecocidal tendencies of endless growth. Today, that arrangement seems paradoxically both incredibly foolish and almost impossible to transform. This is not a conjuncture we will solve by modestly reforming GDP or by just pointing at the big winners of this game (nor taxing the rich, for that matter) and asking them to behave better. Our extremely challenging moment will only give rise to deep systemic positive change if we can, collectively, dream and enact a different form of society altogether, one (or better: many) focused on free and flourishing lives for all living creatures.

Degrowth points precisely at this wide and open road. Let’s walk it together.

Three things you can do right now

- Find out more about degrowth from a Latin American perspective at Centro de Análisis Socioambiental (in English and Spanish) and donate to their important work; or explore the topics outlined in this article more deeply in a piece co-authored by Gabriela: A favor del decrecimiento (in Spanish).

- Help promote this article by sharing these posts on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn. Sign up here for email alerts when articles like this are shared on social media.

- Read about an alternate version of the human story in The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow; or take Gabriela’s module on degrowth, part of the Programa de Introducción a las Nuevas Economías course (in Spanish), starting in February 2022.

Find out more about the Post Growth Institute on our website.

Teaser photo credit: Author supplied