There has been a lot of speculation recently about where the climate movement goes next, from Rupert Read’s call for a ‘moderate flank’ to John Bellamy Foster’s call for an ‘Ecological Revolution’. Anthea Lawson, author of ‘The Entangled Activist’, recently tweeted “Am noticing there’s lots of people that Extinction Rebellion woke up to taking action on climate who are currently marking time, looking for the next thing. A bit like where you hop about waving hands to the quieter bit of a tune, waiting for the beat to drop and everyone will LET RIP”. In this blog I want to offer some thoughts on what that might look like, but from a perhaps unexpected direction, an obscure jazz artist who died almost 30 years ago, Sun Ra.

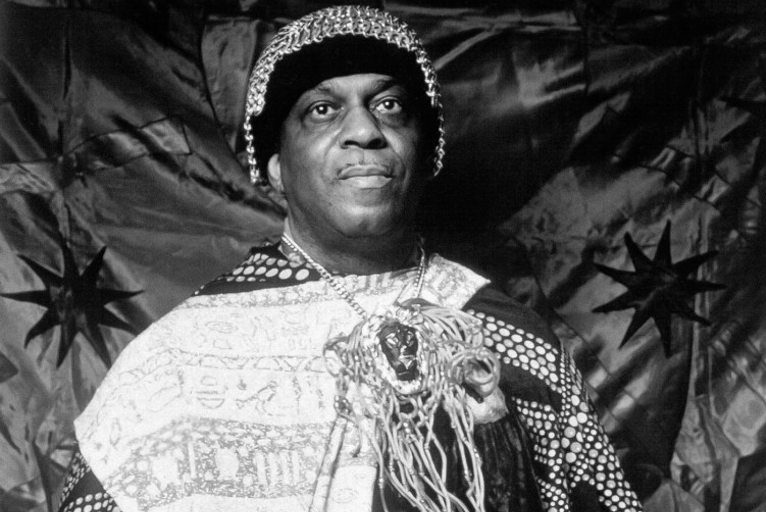

Sun Ra. Photographer uncredited on the publicity photo itself; most likely Francis Ing, who is credited for the photography on Astro Black. Originally published as a publicity photo included with the 1973 press kit for The Magic City reissue. In its originally distributed form, the photograph was printed and published without a copyright notice. Photo retouched by uploader based on high-res scans., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=99369969

Ra was a jazz musician, a band leader, a composer, an artist, a poet, a visionary, a Utopian. Here’s his story in a nutshell. He was born Herman Poole Blount in Birmingham, Alabama, one of the most viciously segregated cities in the US. After spending part of World War Two in jail as a pacifist who conscientiously objected to serving, he moved to Chicago, where as a prolifically talented piano and keyboard player, he found work initially in other bands, eventually creating his own, which came to be known as the Arkestra.

He was an avid researcher into theosophy, the Bible, science fiction, metaphysics, alternative histories of Africa and of black people, Egyptian history and philosophy and much more. As Ytasha L. Womack puts it in her book ‘Afrofuturism’, “he was propelled to answer what others hadn’t questioned and gravitated to books with theories on the origins of the world that differed from the Eurocentric lessons propagated in media and schools”. With members of a secret society called Thmei that he cofounded, he would distribute copies of the group’s thinking in a local park and at gigs.

He changed his name by deed poll to Le Sony’r Ra, then to Sun Ra, and announced that during his time at college in his early 20s, his body had been taken over by a being from Saturn. He once said “I am not of this planet. I am another order of being. I can tell you things you won’t believe”.

The music of his band quickly became a vehicle for spreading his ideas, with songs such as ‘We Travel the Spaceways’ and ‘Astro Black’. The band wore incredible head gear and space garb, and their shows could sometimes last over 6 hours. He was a pioneer of the idea of an independent record company, forming ‘El Saturn’ with his right hand man Alton Abraham, which was part-record label, part-research organisation, part-community organisation.

Ra was also warning, even before the beginnings of the modern environmental movement, about the harm humanity was doing to the ecosystem, talking about how “the landlord is unhappy” at the degree to which the “apartment” we live in is being trashed by the reckless tenants. The more I’ve been reading about Ra, who I’ve come to see as one of the most extraordinary creative artists of the last century, the more I’ve been reflecting on lessons that might inform where we go next as a climate/social justice movement. I’d like to share those reflections with you.

So here are 10 things I think Sun Ra can offer in terms of informing our approach:

One. Improvisation: Ra was a great exponent of the art of improvisation, but rather than seeing it as some kind of freeform noodling, he wanted his musicians to learn the ‘discipline and precision’ of it, that it was a way to become a better, tighter musician, rather than less so.

For Ra, improvisation represented a “manifestation of the possible”. At the heart of improvisation is the ability to respond to ideas and suggestions with a ‘yes, and’ response, rather than the ‘yes, but’ we all too often encounter, both from outside our movements but also from within them. Ensuring that our movements have cultures within which improvisation, a ‘yes, and’ culture, the ability to flex around challenges, is key, a culture of playful activism.

It is said that Ra’s band was trained so that when one member made a mistake, everyone else was to incorporate that mistake into what they were playing. Improvisation is one key tool for eradicating the idea that ‘impossible’ represents any kind of a barrier. As Ra put it,

“the possible has been tried and failed: now I want to try the impossible”.

Artist and interdisciplinary filmmaker Cauleen Smith has written about how improvisation, adaptability and imagination run through all of black music and black culture. In a conversation with Ytasha L. Womack, she stated

“of all the thousands of tribes on the continent, what they all share is this respect for improvisation. That idea in and of itself is a form of technology. In the Western world, improvisation is a failure; you do it when something goes wrong. But when black people improvise, it’s a form of mastery”.

At a time when so many governments, politicians and people seem either resigned to the idea that it’s too late for meaningful action on climate change, or that it would be too difficult, the freedom of thinking that can come through mastering the art of improvisation, the mental flexibility, and the culture of co-creating solutions through ‘yes, and’ is vital.

Two. Being rooted in place: I’ve always been a great believer that alongside the vital work of national and international campaigning, we also need to be rooted in the local, at the community scale. In his great book ‘Sun Ra’s Chicago’, William Sites talks about how, when the band was based in the city, they used local black-owned business, printers, artists, clubs, venues. He writes that Ra was “not a ‘community leader’ precisely – but an anomalous, heterodox figure who nevertheless seemed to be an ever-present interlocutor among them”. Sounds like a good aspiration for those of us doing community activism.

As you might expect me to say as the co-founder of the Transition movement, activism that has its roots in the community is a vitally important piece of the larger puzzle of changemaking. Activism rooted in place is powerful. Activism that builds infrastructure, creates jobs, brings land, buildings and infrastructure into community ownership is even more so. How can our local activism create a story about our place that spreads around the world, an infectious and ambitious story? If your hometown/city/village could be anything, what would it be, and how would it tell that story to the world? And how might that story go onto inspire great change elsewhere? And how might we do it with the bright, bold, colourful, unpredictable, playful-yet-disciplined way that Ra did what he did?

Three. The Project Support Project: ‘Project Support Project’ is an idea I first heard through John Croft’s ‘Dragon Dreaming’ approach, the idea that for individual local projects to succeed, it can help hugely to create a support infrastructure design to make it as easy for them to succeed as possible. It’s what we did in the first couple of years of Transition Town Totnes, creating the bank account, official organisation, website, database, policies and fundraising to enable the individual projects to focus on what they’re best at.

Ra was supported by his collaborator Alton Abraham, in creating El Saturn, an organisation which functioned as a pioneering early independent record label, but also as a research organisation, booker of gigs for the band and much more. In every community we see the emerging reimaginers, the pioneers, the people building what comes next in a low-carbon future … what might the relocalising/decarbonising equivalent of El Saturn be?

Something like Civic Square in Birmingham, or the Onion Collective in Somerset, Atmos Totnes, or indeed Transition groups? The emerging networks of Climate Emergency Centres up and down the country? Projects that recognise the need to build a new infrastructure, responsive to local dreams and needs, building an ‘imagination infrastructure’ from the ground up, combining organising approaches with art, performance, job creation, design, play and so on…

Four. Community as a stage: Ra’s band wore amazing space costumes, golden capes, incredible elaborate headgear. It wasn’t a put on, an on-stage persona. Ra would go to do his groceries in full costume, it was who he was. Being a band of up to 30 musicians (a big band in an age where big bands didn’t exist anymore) it was hard to find anywhere to practice. They would practice in peoples’ homes, in community halls, in venues hours before they were due to actually perform. Sometimes their gigs, complete with electronic sound collages, ecstatic dancers and fire-eaters, would spill out of the venue into a Mardi-Gras style parade down the street (I’d love to see more bands do that…).

Composer and musician Henry Threadgill has talked about the Arkestra regularly gathering to rehearse in the back of a wild game meat market, where they would rehearse surrounded, as William Sites writes “by bear and possum meat”. While this may just have been due to desperation, it also, as Sites argues, was born of Ra’s conviction that “otherworldly music might emerge from practically any place”. Might our activism, visionary and bold and rooted in sharing the futures we imagine, similarly ‘pop-up’ in unexpected places, be something that uses the community around us and its spaces as its its canvas, its stage? If street artists, activists, actors, artists and musicians were to work together skilfully to create really impactful, unexpected moments that bring a future that turned out as best as we could imagine to life in our everyday?

Artist Cauleen Smith did an event with the Rich South High School Marching Band where they played Ra’s song ‘Space is the Place’ in a plaza in Chinatown in Chicago in the pouring rain for an event called ‘A March for Sun Ra’. It’s rather beautiful.

Five.’Everyday Utopianism’: Ra once wrote a poem called ‘Imagination’:

“Imagination is a magic carpet / Upon which we may soar / To distant lands and climes / And even go beyond the moon / To any planet in the sky / If we came from nowhere here / Why can’t we go somewhere there?”

The concept of black people in the US living in a world of “nowhere here”, but dreaming of and heading to “somewhere there”, and of exploring space and inhabiting new worlds, is a powerful metaphor for a deep reimagining of the role of black people in North American culture. Ra once said

“the real aim of this music is to co-ordinate the minds of peoples into an intelligent reach for a better world, and an intelligent approach to the living future”.

There is a long history of black utopianism, of using stories to tell stories of utopias which centre black experience and aspirations. Rather than just being some kind of dreamy utopia, such thinking is often referred to as ‘critical utopias’, which Lyman Tower Sargent defines as:

“A non-existent society described in considerable detail and normally located in time and space that the author intended a contemporaneous reader to view as better than contemporary society but with difficult problems that the described society may or may not be able to solve”.

In my opinion, critical utopias are something we need to become a lot better at, especially if they are crowd-sourced from many different peoples’ visions (as I tried to do here). In my own work, I use my pretend Time Machine in talks to invite people to imagine that they travel forward 10 years to a future that was the result of our having done everything we possibly could have done. What is always striking is the similarly of those visions, how much they actually have in common. Perhaps we should, on a far greater scale, start with the critical utopias and work back from there?

Six. Fearlessness: When I asked John Corbett, writer and Ra archivist and scholar, if Ra actually believed he was from Saturn, he told me:

“Not only do I think he believed it, I believe it… whatever the answer is in terms of how one feels about his use of and his story about his extraterrestriality, Sun Ra was very serious about what he did, and he spent his entire life doing it. There wasn’t an offstage/onstage persona. For me that is evidence of someone whose overall project is not a theatrical project, it’s one that takes very seriously the question of identity and reality”.

Sun Ra’s Arkestra performing in Brecon, Wales, in 1990. Photo: Peter Tea via Flickr.

Could we, as activists, move through the world as people from a future that resulted from our having done everything we possibly could have done? In the Black Lives Matter demonstrations last year I saw a tshirt that read ‘I’ve been to the future. We won’ (I want one). What if our activism took that sentiment and built on it, in a fearless way? I’ll return to this below.

Photo by Made by Rebels, from their Facebook page.

Seven. Humour. In the extraordinary film Ra made called ‘Space is the Place’, there is one scene in which Ra sits behind a desk in a building called the Outer Space Employment Agency. I love the idea of creating things people don’t expect in places they visit regularly. Like the Ministry of Stories in London, the Civic Imagination Office in Bologna, or the Encounters Shops that Encounters Arts ran in a number of places. Spaces that do things you don’t expect and which are designed to welcome you in. Ra’s work is also often very funny, and we should never lose sight of the fact that laughter is a far more powerful way to engage people than despondency.

Eight. Linking past and future: The long tradition of black utopianism is often built on a foundation of what Graham Lock, in his book ‘Blutopia’ describes as “visions of the future and revisions of the past”. Corbett told me of Ra’s “deep interrogation of chronological linearity”, and his deep exploration of the connection between the ancient past and the future, for example going back to ancient Egypt to understand the roots of technology, and arguing that the Moog synthesiser is in fact based on ancient Egyptian technology.

“What enslaved people faced”, Corbett told me, “with the generalisation of their history which leads on the one hand to a dystopian position of not having a past, also opens things up to be reimagined, because there was a past, it’s just been denied you, or your access to it has been obfuscated, which is like an invitation to invent”.

Sun Ra’s reimagining himself was an invitation to black people and others to reimagine themselves…

His music built a bridge between visions of the future and a revised understanding of the past, combining traditional African instruments and percussion, chants and traditional music forms with electronic keyboards and ‘space music’. Ra spoke about his vision of the future. Speaking about his composition ‘Brainville’, he wrote:

“In Brainville, I envision a city whose citizens are all intelligent in mind and action. Every principle used in governing this city is based on science and logic .. all of the institutions stay open 24 hours per day … the places of entertainment never close because people need to be entertained throughout the day … Musicians are called sound scientists and tone artists….”

Generally though, Ra’s approach to Utopia was, as William Sites puts it, “not to detail the content of this world, to provide the blueprint of utopia, but merely to establish its existence as a realm for exploration by the itinerant workers – musicians – whose work it is to travel there”. I feel like we need to be a movement that is able to both talk about the futures that we are already seeing if climate change and social justice go unaddressed (runaway climate change, collapse, fascism etc) as it is our inability to imagine that that has got us into this situation. But we also we need to become a lot better at imagining the world we could still create if we were to be able to mobilise at scale and do everything we possibly could do.

Ursula Le Guin wrote that

“it’s up to authors to spark the imagination of their readers and to help them envision alternatives to how we live”.

It’s up to activists too. As Toni Cade Bambara put it,

“We must make just and liberated futures irresistible”.

Let’s create social utopias with gusto and relish that people can inhabit, and test drive, and have a great time in (like some festivals do).

Nine. Celebrating possibility: Ra once stated that “the possibly has been tried and failed; now I want to try the impossible”. Ra didn’t believe in impossible. He was forever exploring new ideas around space travel, around new technologies, new innovations in sound. As Corbett put it when I spoke to him, Ra’s Arkestra were working at a time when the ‘big band’ era was over. No-one could afford to run a big band anymore, very few places would book them. Having a big band was “impossible”. Yet somehow Ra kept his Arkestra together for almost 40 years. No-one knows quite how he did it. In New York and in Philadephia, the band lived together in the same house, surviving on Ra’s famous ‘moon stew’. While there wasn’t a lot of money around, it worked, just. For Ra there was no such thing as impossible.

Ten: Imagination Infrastructure: how many of this generation’s potential Sun Ras fail to reach their full potential and realise their dreams because the world around them offers little or no encouragement? How many brilliant, left-field ideas potentially vital to the climate emergency never see the light of day because our culture doesn’t value, nurture, or meet imagination in the middle? It has almost entirely been designed out of our education system at all levels, out of most people’s work lives, out of politics, out of public life. We urgently and desperately need to build an imagination infrastructure.

Ra grew up in a house with a big record collection, and aged 11 his great-aunt Ida bought him a piano. Without lessons he began playing by ear, and taught himself to read music. Within a year he was composing songs. Ida took him to see many of the great performers and bands of the time, and by 13 he was leading the school band. Although the underfunded and segregated education system offered little in terms of training or access to instruments, within the wider black community at the time in Birmingham, as John Szwed writes in ‘Space is the Place: the lives and times of Sun Ra’,

“without teachers, even without a source for instruments, a guild system developed in black Birmingham, with older musicians tutoring the young … volunteer school-band directors squeezed rehearsal time in where they could, and they organised professional groups which used students when they played at nights”.

How might we build such a support network for youth activists and climate innovators and social entrepreneurs? How might we build an infrastructure, like the Reconomy Centre in Totnes has done with its Local Entrepreneur Forums, where a community gets behind its visionary entrepreneurs and supports them into being? Might Climate Emergency Centres offer that kind of imagination infrastructure for those coming forward with good ideas? Do we need more things like Encounters Shops, or like Camden’s Think and Do, places on the High Street that invite people in to talk about their hopes and fears and dreams of the future? Building an imagination infrastructure feels to me absolutely essential in being able to address the enormity of the climate emergency.

So, what might all of this mean? Amitav Ghosh wrote recently of how what we need now is a “vitalist mass movement”, a collective work of beauty and art and human spirit, which “may actually be magical enough to change hearts and minds across the world”. Gus Speth recently wrote

“the top environmental problems are selfishness, greed and apathy – and to deal with those we need a spiritual and cultural transformation and we scientists don’t know how to do that”.

I feel like our activism now going forward needs to be a celebration of what’s possible. With the rise of resistance within the Conservative Party in the UK and in many other places too (clearly well-funded and organised) of skepticism about ‘net zero’ (already a wildly unambitious aspiration), the new face of climate denial, embodies a refusal to open the imagination to different ways of doing things. I’d love to see our activism far more like a celebration of the possible, a sharing of stories of what’s already happening, opening spaces for people to dream of what remains possible, creating immersive futures that give people a sense of what might be possible. William Sites writes that Ra’s band was “simultaneously local and extraterrestrial”. Could our activism be simultaneously local and also acting as a visitor from the future? Might we find that playing that role also helps to reduce levels of eco anxiety among our movements?

It’s why every episode of my podcast ‘From What If to What Next’ starts with our time travelling to a 2030 that is the result of our having done everything we can, something guests often later tell me they found really powerful. Clover Horgan, who did it recently on the podcast told me “I really really appreciated this exercise. In fact I wish we asked it in every boardroom and every school around the world”.

What if, as climate activists, we were to respectfully adopt that concept of “I’ve been to the future. We won” and build on it. What if we created ‘critical Utopias’, stories of the future, what Rupert Read has called ‘Thrutopias’ (as in neither dystopias or Utopias, but rather the stories now of how we dug ourselves out of this hole – see also Manda Scott’s new emerging project based on this)? What if we, with the same degree of self-belief as Ra we were to present our events, our activism, as if we were visiting from a future that was the result of our having done everything we possibly could have done over the intervening years? Not some ‘hopium’ version in which climate change has somehow vanished, but a world that did everything it could have done with huge imagination and purpose. What if we could speak from that future? Bring it alive in peoples’ imaginations in the same way Ra used his music to help black people imagine it was they who travelled through space and set up home in new worlds? And why, as activists, do we so often deny ourselves the possibility that our actions might actually achieve what we want them to?

There is, of course, a lot of activism that is colourful and creative. Extinction Rebellion has been amazing at bringing art and activism together in a playful yet direct way. Their last ‘Impossible Rebellion’ picked up some of the themes here. But what if the next one was the ‘Time Travellers Rebellion’, designed around the idea of tens of thousands of people arriving from 20 years hence, stepping out blinking into 2022 to share their stories of how the Great Transition was, what happened, how we made it, how much better life is now that we’ve changed all those things that we’re working in 2022?

John Bellamy Foster recently argued:

“There is no option left but ecological revolution, which means simply that the people, in their endless numbers, will once again be compelled to take history into their own hands, in a struggle that is likely to be stormy and chaotic, but that will also demonstrate the power and endless creativity of humanity, offering the possibility of a new ecological renaissance”.

What if we came from there, and spoke about it, and brought with us artifacts from that future, and shared the heroic tales of how we got there? If we bought with us the new words we needed to describe that future? If we could really share with people how it feels and tastes and smells to live in a world that is far more equal, more just, where the risk of resurgent fascism has disappeared thanks to the building of a more transparent and inclusive society, where biodiversity is rebounding…

Sun Ra once stated that “most of my compositions speak of the future”. Perhaps it’s time for our activism to do the same.