Part 1: Mapping and Matchmaking Efforts in the Informal Aid Ecosystem

“[The] point is not to welcome disasters. They do not create these gifts, but they are one avenue through which these gifts arrive. Disasters provide an extraordinary window into social desire and possibility, and what manifests there matters elsewhere, in ordinary times and in extraordinary times.” — Rebecca Solnit, A Paradise Built in Hell — The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster

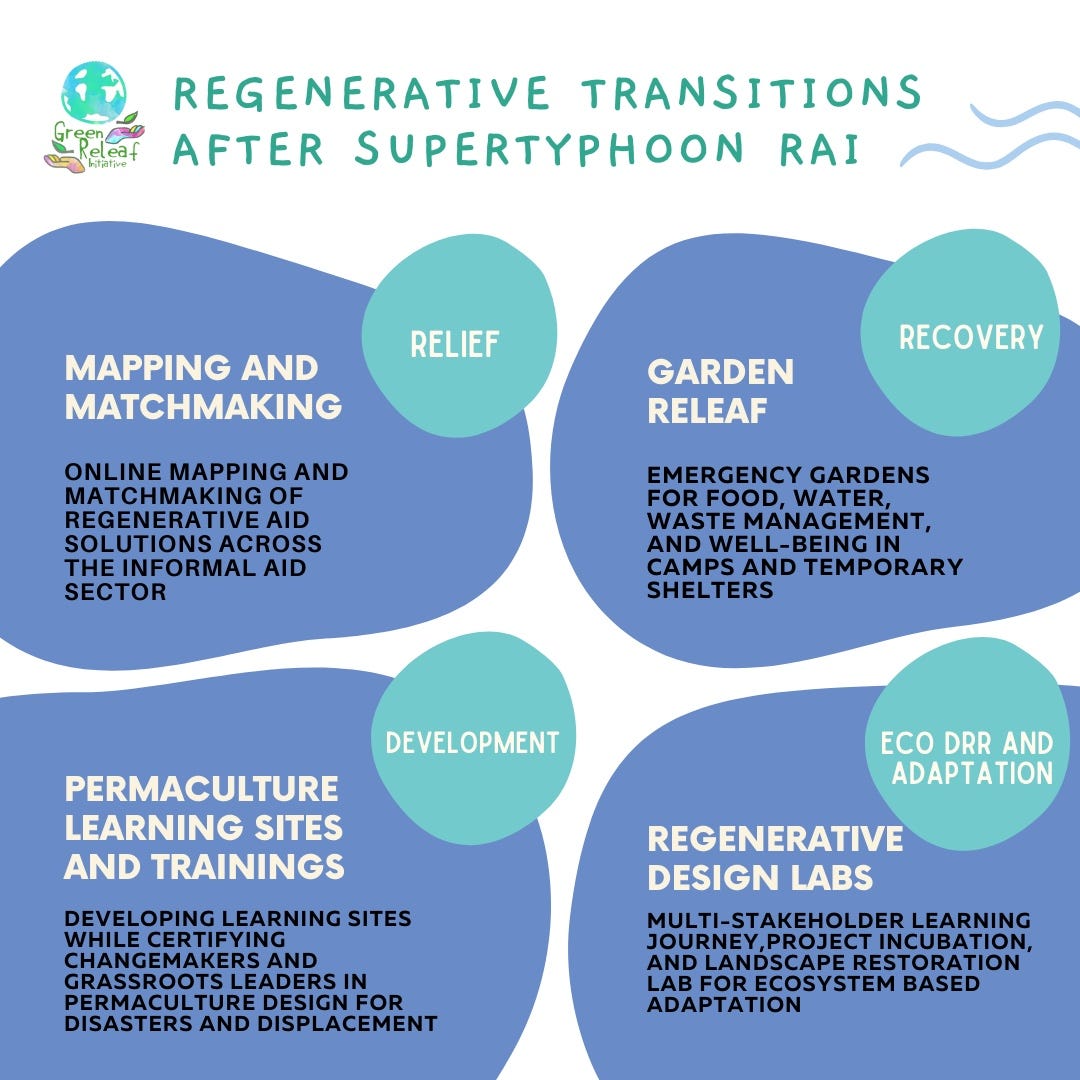

Over the last few years my organization, Green Releaf Initaitive, has been prototyping our permaculture gardens on select sites affected by disasters and displacement. At the core of our theory of change is not just “design” but regenerative design that invites us to go beyond sustainability and ways that we can apply it in contexts of aid and development.

As the Philippines continues to face more and more climate emergencies. we have slowly accepted that we cannot be everywhere every time a disaster happens. Thus, In 2019, we prototyped our Re:Source Regeneration Labs which we launched as part of the Ulab2x with the aim of bringing regenerative initiatives for collaboration together to scale efforts up, wide, and deep.

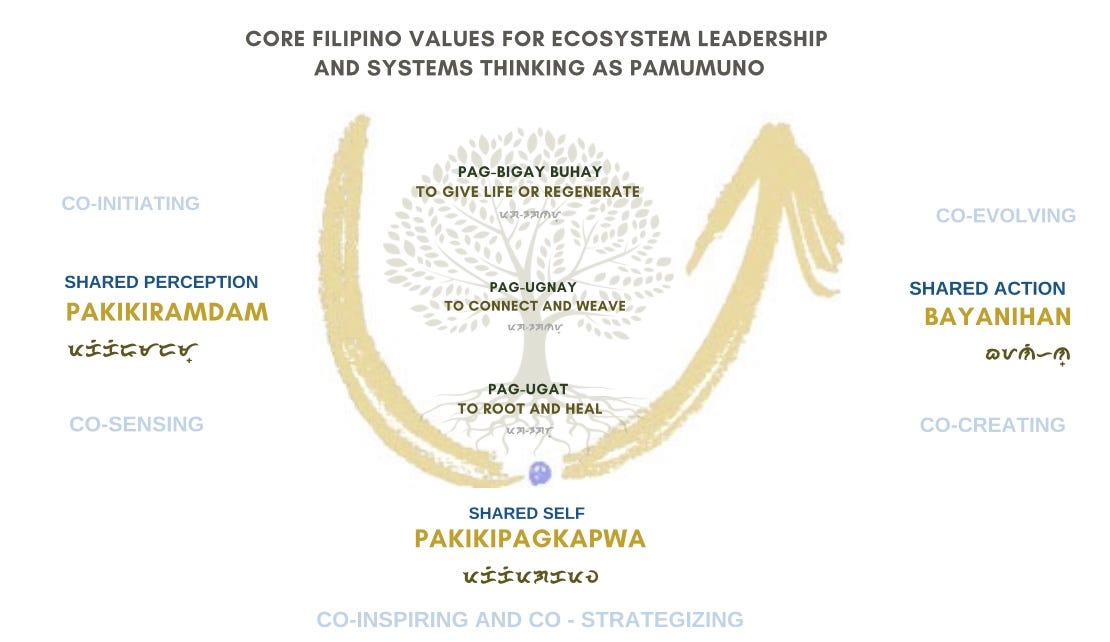

We also combined the two loops model applied by our friends at NewStories to bring innovations together.

In the process, I was able to map out Filipino values and systems thinking in ecosystem leadership that I realized were similar and aligned to these frameworks inspired by the tree- or puno in Tagalog, the root word for Pamumuno, our term for Leadership.

Under this, we prototyped several labs that used regenerative design. We started a zero waste and circular economy ecosystem activation which helped contribute to the National Plan of Action for Marine Litter by UNDP and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Then we ran a regenerative aid lab to bring together informal aid responders for the Taal volcano eruption relief efforts.

Prior to it, we ran a longer “lab” under our Regerative Transitions Program for 3 years, a year after Supertyphoon Haima (local name Lawin) in 2016 in an indigenous community that was affected. We later realised our design was similar with the applied Theory U process of the ULab which we joined in 2019 and integrated the approach. Today we are scaling this in collaboration with Commonland for a landscape restoration lab in key landscapes in the country.

Our first Permaculture Design Certificate Course with grassroots leaders in disasters and displacement with Permaculture for refugees pioneer Rosemary Morrow and Green Releaf Facilitators.

Weaving for Collective Impact

After Taal Volcano errupted in 2019, we were preparing to run our Permaculture Design Certificate Course for grassroots leaders in disasters and displacement to complete our prototypes. We knew we couldn’t be on the ground to help. Given we had limited time, we did a rapid prototyping lab that aimed to sense and cross pollinate across community kitchens, mental health support, livelihood, agriculture, and waste management actors with mappers and aid coordinators.

We came up with prototypes together after some sensemaking and presencing tools combined with regenerative design. Sadly, before we can continue and apply them after the workshop, evacuees were already safe to return home and the pandemic started forcing us to stay home and halt our projects temporarily. However, we learned a lot from this process.

Our Regenerative Aid Lab for Taal Relief (2019) with support by LUSH Re-Fund, in collaboration with Re-Alliance, Project TANAW, The Department of Health, Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT), Art Relief Mobile Kitchen, Feed Philippines, Mother Earth Foundation PH, KindMind, Slow Food Manila, League of Organic Agriculture Municipalities, Cities, and Provinces of PH held at Commune

In the light of super typhoon Rai/Odette which intensified from category 1 to 5 in 24 hours last December 2021, I look back at our insights as we prepare to launch our regenerative aid mapping and matchmaking initiatives. It is my hope that this could help us rethink and reframe how we respond to the growing number and intensity of climate related emergencies everywhere in the spirit of Bayanihan, the Filipino value of collaboration for nation building.

1.The informal aid sector contributes greatly to fill the gap where government and humanitarian interventions can’t meet right away or at all. However, their efforts are not often harnessed to scale for the better.

While we work with humanitarian organizations, we couldn’t identify entirely as one. There is apparently a term to call most relief efforts by communities as “informal aid.” We see ourselves as part of the hundreds, if not thousands of people-led initiatives, that bring together resources to deliver vital needs to those most affected on the ground.

Collectively, we fill the gap of aid when government and international humanitarian sectors can’t do so right away. We started by growing gardens in evacuation centres and in resettlements where displaced people are relocated. Then through our regenerative aid lab prototype, we realized we could instead be an enabler and facilitator for collaboration and possible financing for other NGOs, youth organisations, church groups, and co-workers who raise funds; community pantry organisers; the volunteer bikers who bring aid to hard to reach areas; the mothers who donate breast milk; the farmers who supply vegetable packs; and the mappers who plot where risks and hazards take place — among others, so more can be done together instead of separately.

2. Most communities are not prepared, including those who respond to them. In the end, we often end up scrambling for what to do and how to deliver it in a reactionary way. We end up searching the news or social media channels on how to help and often donate to those we only know. This often leads to the succeeding challenges in the next paragraphs.

3. Most aid go to those that receive most attention and access whether its through the news or social media and/or physical accesibility. A lot of communities don’t receive immediate help right away, if not at all. In a flood of news and posts, a triage of where the most urgent assistance and what kind of assistance can get lost in the information flow. Because of signal challenges people on ground zero won’t have the chance to communicate their needs.

4. Some aid that people receive are not what people actually need. Take the case of the funny stories that came during the Taal relief efforts where wedding gowns and Halloween costumes were donated.

While this particular story can be humorous and can offer lightness to people’s challenges, it can be insensitive to those who just lost their clothes and other posessions. We heard stories where some camps received too many toothbrushes and didn’t know what to do with them. We once did a permaculture garden in a madrasa housing 500 IDPs of the Marawi siege where Muslim IDPs received Christian Bibles along with their relief goods. In the same center, someone donated a bulk of rotten dried fish that were inedible. This showed us that even if people can help, their actions may not be sensitive to people’s culture and needs to help restore their dignity.

5. Some aid go to waste and don’t reach those who need them. Perhaps its the lack of coordination if not corruption, or the levels of bureacracy that delay processing and distribution of goods. We know sad stories of donations uncovered in storage facilitites already expired.

7. Some systemic opportunities to scale or have better impact are lost since initiatives can be focused on their own relief and not in collaboration with others if they are not aware who is doing what. In our Taal regenerative aid lab prototype, we explored, “how can community kitchens work with waste groups to build compost for long term gardens in evacuation centers?” How can mental health groups can work with breast feeding mothers to create safe spaces for women, and how can we map these initaitives so people know where to help?” These are just among other interventions that could be enhanced if people know who else was helping in a specific geographic area or form of assistance.

7. Informal aid efforts cannot be sustained due to donor fatigue and that the disaster eventually becomes yesterday’s news. Aid is necessary for immediate needs during the relief stages but it often loses steam as donors slowly get their funds maxed. Another sad reality is when the attention to the events has been taken over either by other news or another disaster has taken place. Worse, is when existing humanitarian efforts need to move to the next mission due to funding changes, leaving some plans for long term solutions behind.

8. Regenerative aid can be sustained for the long term with local leadership and solutions. If we came in as outsider, it would take us time to develop trust and engage through long social preparation. Without it, most projects fail. Emergency situations don’t have this luxury of time and the assurance that we can stay for long is dependent on funding. Thus, enabling and supporting local efforts would be key to make sure aid goes beyond the immediate assistance needed. They know the stakeholders and they will be there to sustain the work when donors and projects leave.

Lokal Lab’s action plan for Siargao after Supertyphoon Rai/ Odette.

How Regenerative Aid Mapping and Matchmaking Can Help

The idea of a mapping and matchmaking of relief efforts started as an accidental tech pitch. In 2018, I joined a Tech Stars Weekend Start Up workshop for women with the hopes of learning how to become a social enterprise since running a non-profit on our first year since we registered has shown us we need to find ways to sustain our work without being dependent on grants.

However, this course required we had to come up with a pitch project. Racking my brain with what we really needed after working with IDPs affected by the Marawi siege back then, I came up with a pitch for a mock up system to build a relationship across donors, aid providers, and those affected.

Setting up a garden in camps and resettlements takes time before harvesting food, so we wanted to know which sustainable farms are nearby to source vegetable packs for immediate nutritious, plastic free food aid that also offered seeds and cuttings for the garden being grown. The idea of mapping farms and linking donors and camps as the Good Releaf app came in 6th place and seemed to have been received well. However, our team shelved this in the backburner thinking we wouldn’t have the time or resources to make it really work.

After Supertyphoon Rai or Odette ravaged through the Visayas and Mindanao in the Philippines leaving more than 600,000 displaced and almost 400 dead, we stepped back online for a few weeks to give space for the local efforts to raise their resources for immediate relief in the first weeks since supertyphoon Odette or Rai.

Behind the scenes, we have been working with volunteer mappers, database builders, UX designers, social media content generators, and humanitarian innovation specialists to discover ways we can design a platform that can meet design goals to address our learnings above.

We aim to set up a system that would be available for the long haul when donor fatigue sets in, or ways we can prepare ahead for future disasters with a system of information, collaboration, and regeneration can take place not only for informal aid actors but perhaps with institutions like the government or humanitarian organizations who can offer more long term support and resources.

Our mapping and database design team (others not in photo)

We aim to map, identify, and generate relationships across aid providers and solutions; donors and organisers of relief efforts; and organisations on the ground working directly with affected stakeholders. Given the massive scale of relief and recovery efforts needed after typhoon Odette, we are designing the plane as we fly and we are generating resources and support along the way to make our system work effectively.

It is our goal to launch this platform before the month ends with your support and collaboration. Please reach out to me via sarah.queblatin[at]greenreleaf[dot]org to support or collaborate.

This post is part 1 of a series on Beyond DRR: Designing for Resilience and Regeneration as we map out our transition plan for communities affected by supertyphoon Rai/Odette.