While most people associate West Virginia with coal mining, the hills and valleys are also suited for agriculture. And as coal production wanes, farmers are seeing growing opportunities to expand their sector.

Jason Tartt, a farmer in West Virginia, says the Mountain State is fertile territory for honey production and maple and fruit orchards in the flood plains. Tartt, who is Black, sees his role as both developing economic opportunity through farming and supporting other Black farmers in West Virginia.

Growing up in rural McDowell County (population 19,111 in 2020), Tartt remembers that it was commonplace for Black people in his community to be involved in small-scale agriculture, whether they were growing gardens or processing pork and poultry. Those practices tapered off over the years as Black people left seeking better economic prospects in Ohio, Virginia, North Carolina, and Washington, D.C. The population overall in McDowell County has declined by more than 20% since 2010, and Black people make up just 8.5% of the local population.

As a farmer, Tartt’s goals are twofold: build a viable agricultural economy in the county and state, and attract other Black people to see West Virginia, and particularly McDowell County, as a viable place to build a life.

In the United States, Black farmers are an underrepresented group. According to the 2017 Census of Agriculture, 35,470 farms are Black-owned, out of more than 2 million total farms. The majority of farms in the U.S. are owned by White people. In West Virginia, only 31 of the 23,622 farms are Black-owned or -operated. The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that farmers who identified as Black or Black in combination with another race accounted for just 1.4% of the United States’ approximately 3.4 million agricultural producers in an industry that generated $388.5 billion in 2017.

Coal continues to be West Virginia’s most visible industry. In 2020, West Virginia was the second largest producer of coal, after Wyoming, and accounted for 13% of total coal production in the United States. But employment in the coal industry fell 17% from 2016 to 2020, and in West Virginia, the number of industry jobs fell to 11,418 in 2020, down from a peak of more than 100,000 jobs in the 1950s.

Employment opportunities in coal mining were a draw for many Black southerners like Tartt’s family, who migrated from Alabama in the 1920s and put down roots in the Appalachian region that now stretch back four generations. As coal dwindles in West Virginia, Tartt says many people, regardless of their race, are left without much economic opportunity.

“There’s a lot of poverty, a lot of unemployment, those sorts of things,” Tartt says. “A lot of that is because the coal mining industry is gone. In addition to that, it’s almost like these people and this place have been left behind.”

This is where farming enters the picture. Tartt enlisted in the military in 1991 and worked as a U.S. Department of Defense contractor before returning to McDowell County in 2010. In his second career as a farmer, he is using his new role to help educate the local residents about what bounty lies in the flood plains and mountainous terrain. Tartt has piloted growing fruit orchards and making honey on hillsides and has plans to expand. He recently leased 335 acres to build out the hillside growing model.

Shortly after returning to West Virginia, Tartt joined the Veterans & Heroes to Agriculture program run through the state’s Department of Agriculture. The program was started with a mission to help veterans or people transitioning out of the military to enter the agricultural sector.

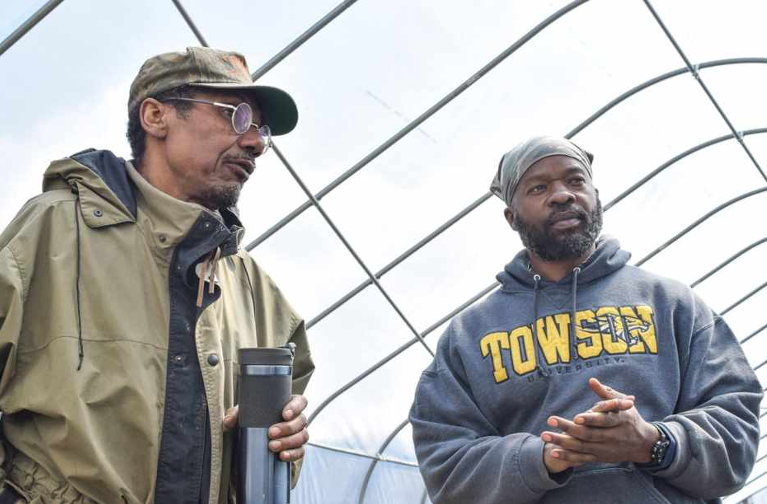

While in the program, he met Skye Edwards, who had learned to farm growing up on the Eastern Band of Cherokee reservation in North Carolina. Tartt and Edwards decided to start McDowell County Farms in 2013.

“[Edwards] was an older man. You know how the old-timers are, they don’t spare feelings,” Tartt says. “They just give it to you straight. He really taught me a lot: the business side of [farming], the science that goes into it. So, he gave me that kind of perspective and really helped me to appreciate what went into this creation, but also how to make the most of it.”

Tartt and Edwards (who passed away in early 2021) linked up with West Virginia State University Extension Service. The program’s overall goal is to empower the public to control their access to fresh food. They do this by connecting farmers, growers, and ranchers from underserved backgrounds, like Black and Brown communities, or other people in Appalachia who are transitioning out of mining and timber and have limited job prospects.

“Agriculture is an essential part of our community fabric, even if people don’t understand that,”

says Christy Martin, the alternative agriculture extension agent in the Agriculture and Natural Resources Division at West Virginia State University.

As in the case with Tartt, the extension program is helping farmers utilize small spaces that have not been traditionally thought of as or intended to be agricultural land.

“It’s like these little, tiny strips in flood plains, or areas that had been an abandoned lot, or something that had been part of a coal or timber operation, and now trying to adapt those to agriculture,” says Martin. “So, in many cases, we’re not dealing in acreage. We might even be dealing in square footage.”

The extension service is piloting a project to grow fruit trees on what was formerly logging land. The benefits are that the roads are already terraced from the logging industry and may make great use for planting orchards.

“And now, that space that wasn’t being used is now a productive orchard,” says Martin of the project.

In addition to orchards, Tartt says West Virginia has plentiful maple trees, which is an overlooked market in West Virginia. Vermont is currently the top producer of maple syrup in the United States, according to the 2017 Census of Agriculture, producing almost half of the nation’s supply.

“A handful of counties in West Virginia could probably produce more than the entire state of Vermont,” says Tartt.

To build an enduring farming economy, Tartt also points to younger farmers, a demographic the farming sector is lacking. In 2017, the average age of a farmer in the U.S. was 57.5 years old. In an effort to attract and develop younger farmers, Tartt founded a nonprofit called the American Youth Agripreneur Association; however, due to the pandemic, the association has yet to operate at full capacity.

“Reaping what you planted in the ground is a beautiful thing,” says Michael Ferguson, president of the nascent association.

Father and son, Jason and Jason Jr. Photography by Suzanne Pender (USDA), Rebecca Haddix (USDA)

Ferguson, who is also Black, grew up in McDowell County and has been growing plants and food since he was young, having learned from his grandparents. He has been farming with the Tartt family for nearly 10 years and has now started his own farm, Ferguson Farms. Ferguson first met Tartt through his son, Jason Jr., when Jason Jr. would sell produce from McDowell County Farms. Part of Ferguson’s role will be to help steward the 335 acres that Tartt has leased. Similar to Tartt, Ferguson would like to use farming to improve the quality of life in his hometown.

Ferguson points to some of issues that have cropped up in McDowell County in recent years, including drug use. He suggests that people have forgotten the farming way of life.

“This is who we are; we’re the Mountain State. We farm around here, and people just forget. I just want to bring it back so you can still live here and have a good life.”