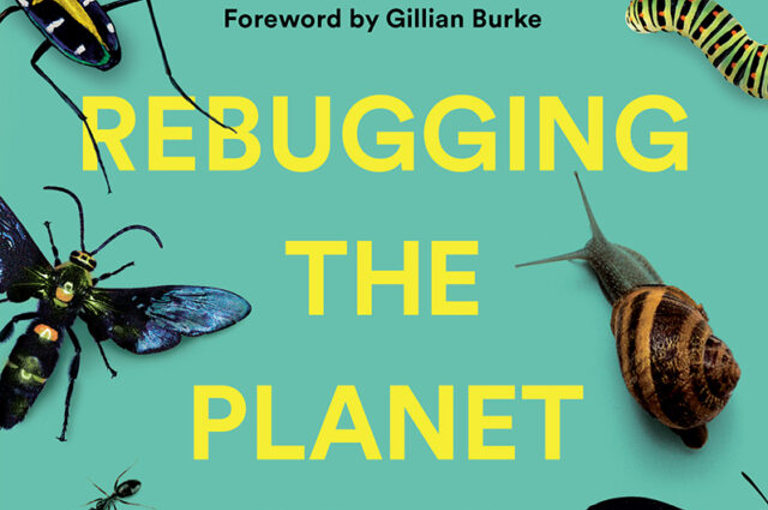

The following excerpt is from Vicki Hird’s new book Rebugging the Planet: The Remarkable Things that Insects (and Other Invertebrates) Do – And Why We Need to Love Them More (Chelsea Green Publishing, September 2021) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.

The following excerpt is from Vicki Hird’s new book Rebugging the Planet: The Remarkable Things that Insects (and Other Invertebrates) Do – And Why We Need to Love Them More (Chelsea Green Publishing, September 2021) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.

What Bugs Do For Us

The truth is that bugs are exquisite in their evolutionary design and they should be able to exists for their own sake, not just for the value in service they give us. But they should be revered for all the vital roles they do play in keeping our only and shared home inhabitable. We just need to see them differently. Looking at a few choice examples of both iconic and totally obscure bugs, I hope to show you their key role in nature and why we depend so much on invertebrates.

Beetles and worms turn waste into fertilizer and food

We would be knee-deep in manure and sewage (not to mention leaf litter) within weeks if bugs did not find organic waste an attractive food and habitat. With over five thousand species of dung beetles, we have an army of tiny waste contractors for every job. They are a keystone species involved in vital ecological systems including soil aeration, nutrient cycling and seed dispersal. Species exist on every continent except the Antarctic, and they are vital and often incredibly beautiful. Soils would be so much poorer without them.

Dung beetles seek out the fresh droppings of animals, then live on this animal dung and even lay their eggs in it. Some roll the dung into tidy balls, which they then use as food and a nest for laying eggs – their hatchlings have a ready-made breakfast. Others live in the dung or tunnel below it, drawing the dung down into the soil.

Many other bugs are vital removers, converters and consumers of waste, including flies and worms. We would find it hard to live around all the dead bodies were it not for the carrion beetles, rove beetles, flesh and blow flies, ants and wasps that feed, and lay their eggs, on dead flesh. Maggots may be revolting, but they are also fascinating and useful – without them, we would soon find the earth unliveable.

Worms deserve a significant mention as they, too, recycle waste materials in a way we could not do without and provide a vital function, which is biological, chemical and physical. They are found worldwide and break down both fecal and plant matter like leaves, freeing vital nutrients for plants and crops to use while also aerating soils. The complex interaction of worms with soil fungi and microorganisms is only just beginning to be understood. The worm is the farmer and gardener’s best friend, but they are so badly affected by the use of machinery, artificial fertilizers, chemicals and the loss of organic matter in soils.

Wasps as plant defenders

Despite a bad reputation, wasps provide hugely important services – from pollination to pest control. Don’t kill them because they are just as useful as bees and ladybirds and remove many flies you don’t want. If you have a wasp nest and can’t leave it, there are many ways to remove it without harsh chemicals, but it’s wise to get expert advice.

I spent a happy summer in the late 1980s in Suffolk, England, breeding a type of miner fly as part of my pest management studies. The leaf miner fly is considered a pest as it lays its eggs inside leaves and, when the eggs hatch, the maggot larvae bore their way through the leaf, making visible white trails. In large numbers, this can lower fruit yields or make plants unattractive as the leaves are covered in white lines. It is a big problem for large glasshouse crops.

My research was to see whether we could rear a small wasp biocontrol in commercially useful numbers for use in glasshouse crops. The wasp is a ‘parasitoid’, which means it kills the fly by laying its eggs in the fly larvae, which then hatch into wasps and eat the larvae as they grow. I scoured maize crops in the hot sun for signs of leaves with the telltale miner lines and tiny hard pupae metamorphosing inside into the adult cereal miner fly. I would then take these leaves and hatch out the flies in cages, provide the conditions and food plants to encourage them to lay eggs and introduce the wasps into the cages I’d built. It was a blissful time and I found enough fly pupae to start breeding before I left to go back to university. The short study showed you could breed these predator hosts in a glasshouse environment. You can buy such wasps to control leaf miner flies in your glasshouse and so avoid the need for insecticides.

The ladybird pest controller

Many invertebrates can be a pain when it comes to food growing. Slugs, aphids, caterpillars, cutworms – all enemies of farmers and gardeners. Billions are spent each year in chemicals and research to kill them off or keep them out.

But bugs can be a huge friend to the gardener and farmer when given the right conditions. One common example is the ladybird, which is a voracious carnivore and can keep aphid numbers at acceptable levels. The fierce-looking larvae of some species – black armor with red stripes –suggest their predatory nature and they can eat up to fifty aphids a day.

Gardeners may also buy tiny nematode worms (bought in the form of eggs, which hatch when added to water) to control slugs and snails. Such ‘biocontrols’ can be self-sustaining – because the bugs breed future generations of the control – harmless to the public and cost effective. The economic value of naturally occurring biocontrols is hard to assess – you would have to remove them to calculate their contribution – but is likely to be billions of pounds annually.

Bugs as pest-management strategies

Bug-based biocontrols are increasingly viewed as useful tools in farming and could become big business, playing a vital role in integrated pest management strategies. This is not new, but against the competition of cheap, abundant and effective chemical pesticides, it has been hard for researchers to devote money to testing and trialling these kinds of tools. But maybe their time has come as society demands less use of harmful pesticides, and as chemicals have started to fail because pests and diseases have become resistant to them. The use of invertebrates in pest and weed management can and should be greatly enhanced.

Globally, the use of biological controls can avert disaster. This was the case with the cassava mealy bug, which by the 1980s was decimating crops in Thailand and causing rapid deforestation in neighboring countries who increased cassava cropping to meet demand. When a parasitoid wasp (which lays its eggs in the mealy bug young, which then hatch into larvae and eat their host) was released, ‘outbreaks were reduced, cropping area contracted and deforestation slowed by 31–95% in individual countries.

Inevitably, given our instinct to be in control, coupled with the complexities of nature, we have made mistakes with biological controls. The deliberate introduction of the cane toad in Australia in the 1930s to replace the toxic arsenic, copper and pitch pesticides in the control of cane beetle pests was a costly mistake. The toad very rapidly became a hugely harmful invasive toxic species, damaging wildlife across large areas and having little impact on the cane beetle. Recently, a biocontrol toad solution may have arrived in the form of water rats. Scientists have observed the rats killing and eating the toads, apparently carving out their organs with ‘surgical precision’. Nature finds a way.

Yet, when carefully applied with expert risk assessments and as part of an integrated strategy, bug biological control can deliver major environmental and economic benefits. Since the late 1800s, it is estimated that over 200 invasive insect pests and over 50 weeds across the globe have been completely or partially suppressed through biological control.