After nearly 17 years of creative resistance and six visits from the man who is now Mexico’s president – three of them in recent months — the tiny colonial town of Temacapulín has become a model in the resolution of water-related conflicts.

“We won this fight because we never lost hope,” said Gabriel Espinoza Íñiguez, the former priest who is now the spokesperson of a movement, at a victory press conference in Guadalajara on Nov. 13. “Because we joined the world movement in defense of rivers, water and territory; because we learned to defend ourselves, together with other communities, struggles and processes that were lived and that some still live with the same threats and abuses; because we said NO to the nightmare of the disappearance of our territory, history, culture and identity.

Para leer este artículo en Español, haz click AQUÍ

“Because we resisted being underwater and being stripped of our roots. Because we united, organized, defended ourselves, mobilized, denounced, sued and proposed alternatives for comprehensive water management in the countryside and in the city. Because we learned the rights that we have as rural peoples, but above all because we love our land and we love our river.”

“Victory for the Peoples,” reads the celebratory poster at Temaca’s victory press conference on Nov. 13. UN Special Rapporteur Pedro Arrojo stands at the center, holding a banner with an image of Temaca’s now-famous basilica and the words: “WATER AND PEACE FOR ALL. LONG LIVE THE REVOLUTION OF WATER.”. (Tracy L. Barnett photo)

Coincidentally, UN Special Rapporteur on the right to potable water Pedro Arrojo was in Guadalajara to work with the Senate on a new water law at the time of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s third trip to Temaca as president on Nov. 10. As a longtime supporter of the villagers’ cause, Arrojo was delighted to travel to the village and to be present as López Obrador announced the acceptance of Temaca’s conditions for the operation of El Zapotillo. And to take advantage of his presence, and to celebrate their historic victory, the Committee to Save Temacapulín, Acasico and Palmarejo called a press conference.

After listening attentively to Espinoza, other villagers and members of the committee’s technical team, Arrojo spoke. The internationally beloved Spanish physicist, economist, environmentalist and leader in the movement to guarantee the human right to water, winner of the Goldman Prize, considered the Nobel Prize for the Environment, Arrojo had followed the case of Temaca for years and was well known to the villagers and their supporters. He commended the villagers and their advisors as “excellent professionals” fully capable of holding their own on the world stage, with “reason, arguments, alternatives,” in a non-violent way. And then he brought up a fact not often recognized.

“You have been able to do something that I want to present to the world as a positive example,” Arrojo said, gesturing toward a diminutive figure in the front of the audience. “As I said the other day in Temaca, it is the leadership of women like this Señora Marichuy (María de Jesús García, the grandmother who had become one of the movement’s staunchest leaders), of perseverant struggle, of intelligent struggle, of struggle radically linked to a dignity that does not go away. You may lose or you may win, but you will never quit.”

Gabriel Espinoza accompanies some of the longtime stalwarts behind the movement, the Carbajal sisters and Marichuy Garcia: from left, Panchita Carbajal, Rufina Carbajal, María de Jesús (Marichuy) García, and Lolita Carbajal. (Tracy L. Barnett photo)

The week before, on Nov. 10, Espinoza and Arrojo both joined López Obrador as he stood under the arches of the town’s is historic plaza, flanked by his entire cabinet, and ratified what he had told the people on his first visit as president on Aug. 14: that they would be the ones to decide the fate of the multi-million-dollar El Zapotillo Dam, which, if finished at the 105-meter height that was planned, would flood Temaca and two other villages.

During that visit, the president announced the cancellation of the plan to create an aqueduct that would send much of El Zapotillo’s water to the neighboring state of Guanajuato. If they were able to reach an agreement that the villagers could accept, he said, the water would stay in the state of Jalisco, and would be destined for people rather than industry in its capital city of Guadalajara. He also said that whatever was decided about the dam, the three villages would not be flooded.

If finished at the 105-meter height as initially planned, the dam would flood Temaca and two other villages. The partially finished dam is currently 80 meters high, and as per the new deal, it will go no higher. Photo José Esteban Castro / WATERLAT GOBACIT.

After the president’s historic visit, a series of complicated negotiations began, first among the villagers themselves, and then between the National Water Commission and the villagers. It took nearly two months to define the “Agreement of the Campesino Villages of Temacapulín, Acasico and Palmarejo.” By October 10, when the president returned to Temaca again with Jalisco State Governor Enrique Alfaro Ramírez and the head of the National Water Commission at his side, the villagers were ready with a compromise offer.

Much was at stake: On the one hand, Guadalajara, as well as the industrial city of Leon in the neighboring state of Guanajuato State, were suffering serious water shortages, and several administrations were relying on El Zapotillo dam to solve the problem. On the other hand, the villagers who live downstream had fought for nearly a generation to stop the megadam project. The villagers were worried about the safety implications of the project. With climate change causing increasingly severe flooding over recent years, their village’s location at the bottom of a deep valley had them fearing for their lives and the fate of their agricultural lands.

On Nov. 10, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador returned to Temaca and presented a 15-point plan for the development and wellbeing of the villages that addressed most of the villagers’ concerns. He also agreed to a technical and financial audit of the El Zapotillo dam. Photo by Tracy Barnett.

So several hundred observers waited with bated breath as a lineup of villagers took the stand and addressed López Obrador. Gabriel Espinoza was the last to speak. “Padre, Padre, Padre,” chanted the villagers, who still call Espinoza “Father” years after the church stripped him of his position for his refusal to leave the village and the struggle to save it.

“Mr. President, there’s something very important that you said two months ago on the stage of the El Zapotillo Dam,” said Espinoza, his face serious beneath his trademark white cowboy-style sombrero. “You said, ‘The people are not stupid; the stupid ones are those who think the people are stupid.’ We know what is good for us and what is not good for us.”Espinoza laid out the six-point agreement the villagers had drawn up with the support of their technical advisors. It said the villagers would be willing to accept a compromise of a dam with a shorter height, with multiple safety measures in place to guarantee their security in case of a 1,000-year flood. In exchange, they would require restitution for the human rights violations they had suffered over the past 17 years and a full technical and a financial audit of the dam to identify the misuse of public funds.

“Our greatest desire, Mr. President, is the peace that was stolen from us by the imposition of the El Zapotillo dam in our territory since 2006,” Espinoza said. “Every day we dream of reactivating our economy, reviving and strengthening our communities, exercising our right to development and the self-determination of our peoples that were truncated.”

He then presented a detailed “Justice Plan” for the communities of Temacapulín, as well as Acasico and Palmarejo, the two other downstream villages that would be impacted by the dam. At the top of the list: the restoration of the Río Verde (Green River), which has suffered extensive damage not only from the construction of the dam but also from ongoing gravel mining. The villagers demanded cancellation of all mining concessions in the river.

Next on the list were economic reactivation and community development plans for the three villages: A program to support the fields and livestock for the communities, strengthening their infrastructure, roads, highways, paving, cobblestones and other services; strengthening health, education and culture programs; and the designation of Temacapulín as a Pueblo Mágico (“Magical Village” — a designation that puts the town on the international tourism map).

Other demands included the right to return for the community of Palmarejo, whose residents were forcibly evicted during the early years of the dam construction project, reconstruction of the Palmarejo and Acasico communities and all their services and infrastructure, and a presentation of public apologies to all three communities.

The agreement affirmed the cancellation of the planned aqueduct that would have transported the water to Leon, and the intention that the Río Verde waters were to be destined to the people who most needed it, and not for industrial uses.

“Since the Sixth Century, Temaca Salutes You,” proclaims a hilltop overlooking the village. Temaca traces its origins to an indigenous Caxcan village founded long before the arrival of the Spaniards, and who fought valiantly to retain their autonomy in the face of colonization. (Tracy L. Barnett photo)

López Obrador took the stand to rowdy cheers, still wearing the garland of seasonal orange marigolds, a marked contrast to the boos that confronted Alfaro when he appeared at the president’s side. Alfaro had promised the villagers he would stop the dam when he was campaigning for governor, but quickly changed his position once elected. Cries of “Fuera Alfaro!” (Get out, Alfaro!) erupted at his appearance, and he quickly removed the garland from his neck.

López Obrador, on the other hand, enjoyed an easy rapport with the crowd. The president seemed more than amenable to the villagers’ demands, telling them that he believed the National Water Commission’s plan would have kept them safe, but he understood that they felt they needed additional measures as recommended to them by their own technical advisors. “If budget is required, I can do it,” he said, smiling at the cheers.

There would be budget for a program for the wellbeing and economic development of the villages, he promised. There would be budget to rebuild the homes that were torn down. There would be budget for the safety measures, including a diversion channel and even a tunnel if necessary. Furthermore, he said, the budget would be managed by the local people themselves instead of the government, ensuring a level of “co-responsibility.”

“We are going to make this issue, this conflict, something exemplary,” he said. “That is, we are going to show all Mexicans and the world that you can negotiate in good faith, reach agreements and solve problems — even the most difficult — when there is a will, and when you govern with justice and you have a conscientious people, an honest people, like the people of your town, the people of Temacapulín.”

López Obrador ended his comments with a promise to return in two months’ time, to finalize the agreement.

For nearly 17 years, the people of Temacapulín, a remote pueblo of 400 full-time inhabitants in Jalisco state, have mounted a fierce opposition to the $3.6 billion El Zapotillo megadam project. Photo by Tracy Barnett.

In subsequent days, the villagers’ technicians stepped forward to clarify details of the plan.

The restoration of the Río Verde was a key part of the safety plan, Tunuary Chávez of the Jalisco Human Rights Commission told Earth Island Journal. Without it, landslides were inevitable in the highly erosive cliffs that had been cut away to build the dam, and the debris would likely clog the channels that would be built to keep the villages from flooding, said Chávez, who is a specialist in environmental engineering and hydrology and a member of the technical team that had worked alongside the villagers.

Amplifying that assertion was the testimony presented by several members of the technical team of the Committee to Save Temacapulín, Acasico and Palmarejo, during an October press conference two days later.

The conference included surprise guests, beamed in via Zoom on a large screen from Holland —hydrology experts from the Institute for Water Education, a program of the United Nations, Dr. Pieter van der Zaag, Dr. Nora Van Cauwenbergh and Mexican doctoral student Jonatan Godinez Madrigal.

Local and visiting artists have made Temaca a showcase of resistance over the years. “I, A Free River,” proclaims this mural, one of many. (Tracy L. Barnett photo)

Together, with Guadalajara civil engineer Jorge Acosta, they presented a heavily documented report, which included inputs from the hydrology experts, that argued the National Water Commission’s original plan for the dam was seriously flawed, both in design and construction materials used, and would leave the villagers at high risk due to landslides in a region that was not suitable for large dams. Dam opponents had been making this argument since the beginning of the project. Now it was being corroborated by international researchers.

Van der Zaag, who has written a book on corruption in water management practices in Western Mexico, congratulated the people of Temaca for their “dedication, tenacity, and persistence.”

“I am also very impressed that the Mexican president has carefully listened to you, and that he has said that he wants to do exactly what you have proposed,” he said. “So I congratulate the people of Temacapulín, and also the people of Mexico, for having such a wise president that listens to the community. I am very happy that my Institute in the Netherlands has been able to support the communities with their rightful ambitions and struggles for water justice.”

On Nov. 10, López Obrador kept his promise to return — this time with the entire cabinet of the federal government — to finalize the agreement. He presented a 15-point plan for the development and well-being of the villages that addressed most of the villagers’ concerns while also addressing the water needs of Guadalajara. He also agreed to a technical and financial audit of the dam.

Gabriel Espinoza, former priest and current farmer, activist, scholar and businessman, is also an accomplished mariachi singer and songwriter. Here he crosses the town’s historic plaza with a member of a band he helped to found as they prepare to celebrate AMLO’s visit. (Tracy L. Barnett photo)

Espinoza, reached by phone the following morning, was cautiously elated. A few details remain to be resolved, and the communities will remain vigilant, he said. But now they are entering a new phase: Instead of opposing the dam, they are going to be working with the government to make sure that its completion and eventual operation are done correctly.

“It was a symbolic day for us, a day in which we celebrated the Revolution of Water that we declared on Nov. 10, 2010 in the heart of Guadalajara,” Espinoza said. “We have accepted this challenge, this new stage, with much hope that the people will continue to participate more broadly. That is one of our challenges. The president himself encouraged us to be honest, responsible and in search of projects that really benefit all of the families — and, we think, not only the families of Temacapulín, Acasico, Palmarejo, but the families of Jalisco, Mexico and the world.”

An earlier version of this story was written for Earth Island Journal.

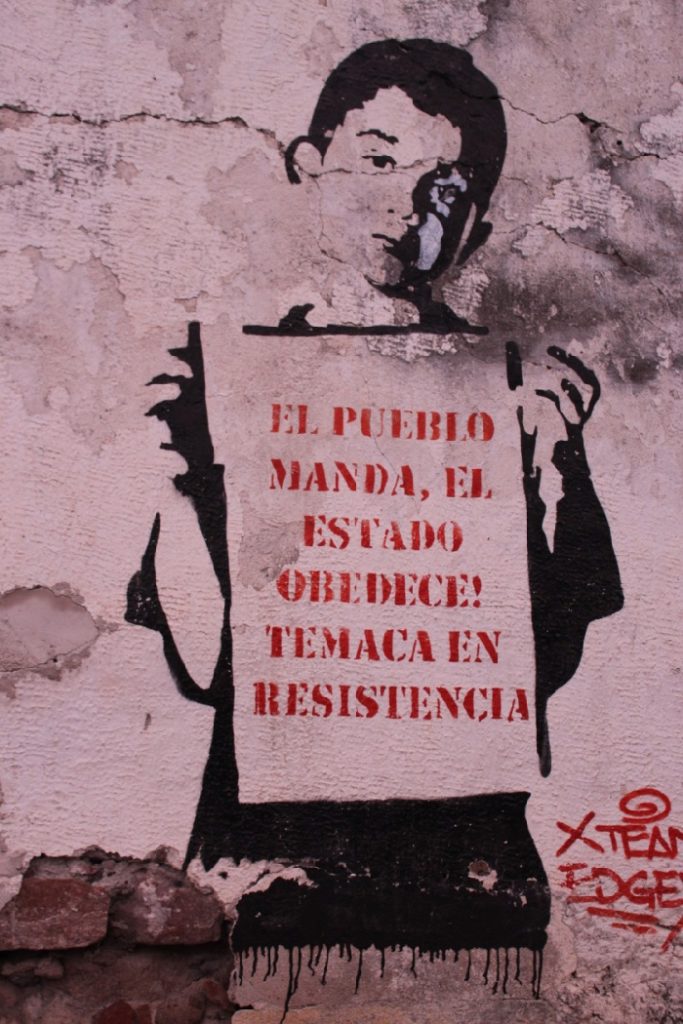

A mural on a Temaca street corner bears a famous phrase by the revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata. These days it carries an almost profetic tone: “The people rule, the state obeys.” (Tracy L. Barnett photo)