Readers of this blog will know that I have come to some big-picture conclusions about success and failure that are unsettling. I don’t like them myself. Not only do they create an inner sadness about where I think the human endeavor is heading, but they result in a sort of isolation that I would rather not suffer—introvert though I am. Among other academics at my institution, it is rare for me to find kindred spirits, even among groups self-selected to care about environmental issues. Most don’t seem to see very far beyond climate change in the lineup of existential threats, increasingly focusing on inequities within the human population that stem from climate and environmental disturbances. I am glad that climate change awareness is high (a genuine threat), but even if climate change had never arisen, I think we would still be in grave trouble from the more fundamental flaws in our explosive approach to living on Earth.

This is a large part of the impetus behind PLAN, which I announced in the last post. Already, I am gratified that people joining the network from vastly different fields and experiences have formed similar conclusions at the highest level. So I’m not crazy, unless we all are. In any case, I am less lonely. [I will say that crazy is usually easy to spot in conversation: a little too insistent/enthusiastic/one-track. The PLAN folks feel really solid, broad, and even perhaps subdued to me: not the type you want to back away from at a party.]

But I still try to understand why so few of my colleagues have reached similar conclusions. The easy answer is that I’m just plain wrong. But believe me, I have tormented myself to try to discover the missing piece and go back to being a happy human bumping along in this race to who-knows-where. It’s not that my unconcerned colleagues have thought more deeply about the issues and can help a rookie out, in my experience.

In this post, I venture some guesses about the disconnect—some of which may even be on target. I will loosely frame the discussion in the context of academia, but much of the logic also applies beyond this scope. The basic idea is: complexity makes it hard to differentiate between real and artificial worlds.

Too Much Confusion

Sharp minds are capable of coping with complexity, and are apt to revel in the convolutions and nuances of ideas. Thought feeds the soul, for the intellectual sort.

In the panoply of fields and ideas represented within academia, one finds a rich ground of substantive topics to consider or debate. Is the construct of capitalism the source of our modern problems, or does the simple mechanism contain the seeds of salvation? Is communism a better system? Has communism been shown to fail by example, or has “real” communism never been tested? Is it even possible to achieve a pure enough instantiation, or will human nature prevent such a test—and if not, is it relevant? Would redistribution address inequity? If our system prevented the rise of multi-billionaires, or limited corporate power, would many of our problems melt away or become worse in some other way? What role does religion play? Is any one flavor better than another, or would we be better off abandoning faith altogether? And are we still making progress on racial equality, or are we lately lurching backwards? Does authoritarianism threaten to derail seemingly stable democracies?

Amidst all these concerns, isolating the problem and devising a system that would tame our most significant ills seems to be hopelessly mired in complexity. Opinions/ideas abound, making it effectively impossible to arrive at consensus on the relative merits of ideas. So the wheels of academia spin, churning out heaps of well-considered publications, and sometimes achieving demonstrable bits of progress.

The Two Worlds

A Planetary Limits perspective steps to the side and starts by acknowledging a non-negotiable physical basis to everything.

In this view, we have created and prioritized an artificial world atop the real physical world, full of constructs that are malleable and in some senses arbitrary. Perhaps because the elements of this attention-dominating artificial world are of our own creation—agriculture, cities, political and legal systems, economies, industry, gadgets, entertainment, etc.—we acquire the illusion that we really are masters of the world and can design it to our collective wishes. The focus becomes on maneuvering through these complex constructs (political, legal, monetary, social) to achieve our goals. The canvas appears to be unconstrained, inspiring a certain enthusiasm for the “possible.” It is easy to overlook the fact that this artificial world has not stood the test of time, as the real physical world has by construction.

Meanwhile, the physical foundation is taken for granted like the air we breathe; or at least relegated to engineering “problems” to be solved. Our tendency to is throw physical considerations into the mix to swirl among all the other complexities: just another “pet issue” on an equal footing, and therefore as debatable, fungible, or perhaps ignorable as all the rest.

As an extreme example: whatever your passion, try making your case without any air in the room. Not only won’t the sound propagate, but you’ll be in a bad way for oxygen. Try maintaining your position for days or weeks without allowing any intake of water or food. The physical foundation is so obviously important as a prerequisite for anything else that it deserves its own (necessarily finite) canvas, within which everything else must operate in deference to the limitations/boundaries. Yet we take it for granted: treating something of paramount importance with little regard.

But is it Critical?

It makes sense that we do this, when hard limits have seemed remote or irrelevant this past century and more. The oxygen example above borders on ludicrous, since we are not in serious jeopardy of running out of air to breathe—space fantasies pushed aside. Food and water are less guaranteed. But generally speaking, ignoring physical limits is unwise when suddenly 8 billion people are scooping out the inheritance of Earth’s finite one-time resources as fast as humanly possible. We have not seen the full consequences yet, and can no longer take the foundation for granted, as we have already used up a shocking fraction of Earth’s offerings in the blink of an eye on timescales of evolution or even of civilization. We are chewing on the power cord to our life support machine, as if it’s just another fun choice on the menu. It’s the worst choice we could make, as exciting as Amazon deliveries might be.

To most, it seems that physical resources have always been available in sufficient quantity—notwithstanding costs that act to curb our appetites, operating as a crude and imperfect signal that quantities must be limited in some manner. The problem is typically conceived to be one of efficient organization and distribution, so that physical availability takes a back seat to human-controlled factors.

Perhaps a useful way to drive the point home is to pause and look around you. Most eyes will land on a lot of physical “stuff.” Or think about the stream of delivery trucks, unloaded car trunks, and curbside waste as a marker of material throughput in most households. Where does it all come from? Is the source limitless? Could you gather the resources that make your life possible on your own little patch of land: metals, plastics, wood, energy resources? Who, in fact, can? Or can you at least offer something of value that can be traded for things you don’t happen to have on your property? Can the things you need even be sourced in your local region? The stuff we rely upon is not exactly easy to acquire, and it gets harder as the prime resources are fully exploited/depleted on this ever-smaller globe.

Dismissing Limits

Ignoring physical limitations allows human exceptionalism to take center stage, subsuming physical concerns under the “engineering” category of human mastery. And many engineers are perfectly happy to receive well-defined “kit” to puzzle out, creating the temporary illusion that cleverness triumphs over natural limits.

Space fantasies fall into this category: thought to be just a matter of the political stars aligning and some advances in engineering. Never mind the question of whether Earth even has the resources to launch a large human footprint in space, or the staggering paucity of resources in that hostile environment. Those considerations were not part of the kit, and take away from the fun.

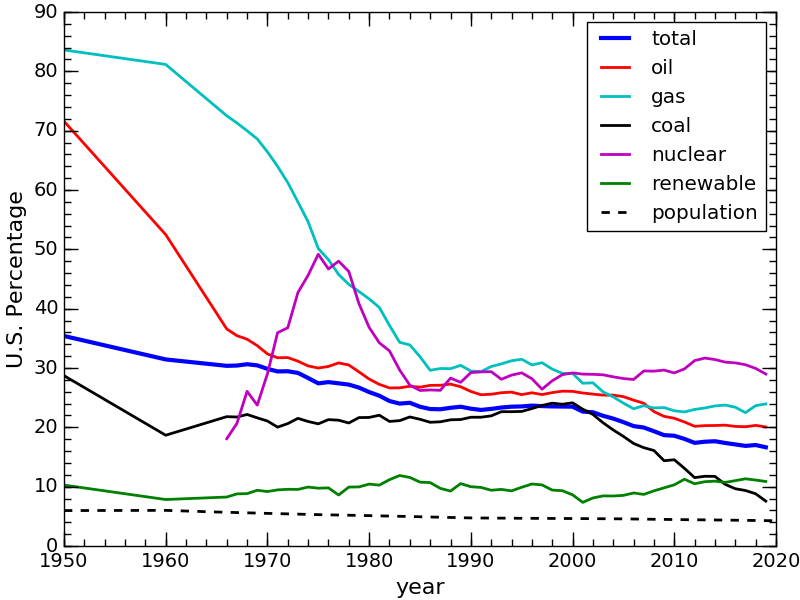

Percentage of global energy resources consumed by the U.S. over time. The dashed line at bottom represents the fraction of U.S. population in the world, so that energy use above this line means a greater-than-average share, which is true for all sources.

In this context, I am reminded of the physical basis for American dominance in the latter half of the 20th century. A plot of the fraction of global energy resources consumed by the U.S. during this period is eye-opening (Figure 7.9 in textbook, reproduced above). Having only 6% of the world’s population in 1950, the U.S. used over 70% of oil, and over 80% of natural gas. This qualified the U.S. as a literal superpower, following the physics definition of power as rate of energy use. It wasn’t just energy. The North American frontier was laden with physical resources primed for exploitation. A common sentiment is that America should return to those glory days (not great for all, I note)—as if it’s a matter of attitudes or ideologies. No! It was a reflection of physical dominance. We’re not going back there, no matter how we cast our votes.

Another common focus of how we might fix many of the world’s ills is redistributing the wealth of billionaires. But perversely, perhaps locking up the wealth without physical expression is doing more good than harm, in Earth’s eyes. If a multi-billionaire released, say, $30k each to 1 million people, we might expect 1 million car purchases, or the equivalent. Yet billionaires don’t have million-car garages. In general, because only a tiny sliver of energy and material resources go to the few billionaires (disproportionately small compared to their wealth), I would expect redistribution to result in a substantial increase in energy and material resource consumption: more fossil fuels; more CO2; more deforestation; more mining; more Amazon and back to billionaires! It’s a large part of what drives the appeal of redistribution: more access to “stuff” for the masses. What would the forests and animal kingdom want? Prioritizing people and their wants over ecosystems is a losing strategy, in the end.

Our tendency to ignore the value of physical resources in relation to our artificial pursuits is also seen in the way we treat resources as essentially free in our price structures. The cost is dominated by the extraction effort (a human activity), land rights (another artificial construct), and maybe a little profit for those who have the means to secure and perform the extraction/exploitation. No one pays into a global coffer for the extracted oil, or the cut-down tree. The actual thing that’s valuable is plucked for free—uncompensated. No wonder we fail to properly value those resources as special. Our woefully inadequate construct of money is not up to the task of protecting our life support machine.

Good News: Bad News

As a jarring illustration of our tendency to value the human side over the prerequisite physical/ecological side, imagine that somehow we manage to emerge from the coming centuries having established a truly sustainable existence. All resources are renewed by nature at the rate of extraction for human needs; population is steady and at a level just tolerable to the planet in terms of indefinite support. Diverse ecosystems are left to thrive in their natural states. But imagine that we are still plagued by cancer and other maladies, so that life expectancy is, say, 90 years.

Then what if a team of researchers hits on a cure for (most forms of) cancer? Hurray! At last! Unambiguously good, right?

Well, not so fast. All other elements held the same, longer life spans translate to a higher population, putting additional resource burdens on the planet that it cannot handle in the long term. In order to adopt and implement the cure for cancer, we would have to either deliberately reduce population or lower the standard of living to accommodate the change. All other considerations of the complex society about economic impacts, equity of distribution, legal and political facets, or interaction with religious belief systems must take a back seat to the most fundamental and important question: is this change physically viable on this finite planet in the long term?

Physical Priority

Physical limits should be the start of every discussion. Every policy, every philosophical argument, every religious choice, every economic decision should first consider the immutable impact on the physical world: the real and non-negotiable world. Will the proposal have a net negative or a net positive effect on ecosystems (neutral also okay)? Only after planetary limits are respected should considerations in our artificially constructed world be applied. Otherwise we write the prescription for failure.

Picking up some language from a recently-joined PLAN member, one might say that most of our constructs are downstream from physical considerations. I think this is a helpful way to frame it. Carrying the metaphor, the culture of a village on a river bank might be richly interwoven with the river. Rules about water use for drinking and irrigation, fishing, swimming, washing, and waste disposal mix with religion, history, personal stories, and down the line. But if the source of water—high in the mountains and out of sight—is disturbed or eliminated, all of that defining complexity becomes essentially meaningless.

Human civilization is downstream from the provision of physical resources and planetary health. We need to set aside distracting complexities until we get this part right.

It turns out that what’s good for humans (in the short term) is not necessarily good for nature. In our current—utterly unsustainable—mode, choices that are thought to be good for humans are usually decidedly terrible choices for the planet and therefore ultimately bad for us, too. Take care of the real world first, and then you can have dessert.

The overall point is that the world in which we operate is divided into the physical and the philosophical. One is real and not the least arbitrary or negotiable in its rule set. The other is imagined to enjoy great freedom from constraint, encouraging us to paint anything that pleases. Lumping them together in a confusing mash of relativism is bound to result in ultimate failure, because it’s just wrong. The canvas is not unbounded, so adjust your painting ambitions accordingly, before applying the first stroke.

[The last sentences in each of the last three paragraphs convey a very similar message. Apologies for any resulting sense of repetition, but I became attached to each version.]

Teaser photo credit: From analogicus, via Pixabay