By Tracy L. Barnett and Hernán Vilchez

with production by Amado Villafaña in the Sierra Nevada and Sebastian Coronado in Bogotá

Academic support from Álvaro Sepulveda from the Colombia Ethnobiological Society

This story is Part 3 of the transmedia series “Cosmology & Pandemic — What We Can Learn from Indigenous Responses to the Current Health Crisis,” produced with the support of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, The One Foundation and SGE. Episode I: The Body as Territory begins the series with three stories from three different indigenous communities in Colombia. For more about this series, see cosmopandemic.esperanzaproject.com.

Ed. note: You can find Part 1 and Part 2 of this series on Resilience.org.

When news of Covid-19 came to the enigmatic white-clad peoples of the high Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta, nobody was very surprised. The four indigenous groups that reside in the region and refer to themselves as the Elder Brothers – the Kogis, the Arhuacos, the Wiwas and the Kankuamos – had already received numerous warnings from their spiritual guides, the Mamos, and their female counterparts, the Sagas.

Lea este artículo en español AQUÍ.

Trained since birth in the ways of looking to Nature for guidance, these spiritual guides of the Sierra Nevada predicted this pandemic and other current crises decades ago. The Mamos have been saying for years that the Earth would be plagued with “unknown illnesses” – along with climate change and water and food shortages – as a consequence of the environmentally destructive practices of the “Younger Brothers,” meaning non-indigenous society. Humanity must return to the Law of Origin — the original instructions given on how to cohabit in a harmonious way with life on the planet — or be subjected to increasing levels of crisis, they believe.

As Mamo Camilo Izquierdo said, “The destruction of nature produces illness from the diseases that we see today.” The wellness of all beings — including the living water that springs from the earth — is essential for our own well-being.

For the peoples of the Sierra, the spiritual territory is superimposed on the physical space, and a vital part of their work is to take care of this sacred geography at all its levels. Photo: Esperanza Project – Cosmology & Pandemic

The first of four pandemics

The Mamos have been trying for decades to get the attention of the Younger Brothers, to help us understand that what we are doing is fundamentally wrong and will lead to dire and potentially irreversible consequences. Now they say that Covid-19 is just the first of four pandemics, unleashed as a “warning bell” to wake humanity from the bad dream of modern civilization.

Mamo Adolfo Chaparro traces the origin of the illness to the beginning of time, when humans were given the Law of Origin to follow.

“We are passing through a pandemic because we have broken those rules,” he explains. “It is our responsibility to keep them under control. Because we have stopped caring for the Mother Earth, we are turning into food for illnesses, and the same thing is happening with the Younger Brother.”

But this is just one of the crises the Elder Brothers have been foretelling for decades. They have watched with increasing distress as their snows have melted, their rivers have shrunk and their rains have dwindled, and along with them, the crops that feed their people.

For the Mamos, Covid-19 is only the first of four pandemics, unleashed as a “bell” to awaken humanity from the nightmare caused by the predatory practices of modern civilization. Photo: Esperanza Project – Cosmology & Pandemic

In 1990, they opened their territory for the first time to outsiders, inviting the BBC film crew that made the historic film “From the Heart of the World: Elder Brothers’ Warning.” Twenty years later, surveying the global landscape, the Mamos consulted the origins once again and realized the Younger Brothers had not received their message. They made another film, Aluna, and they also launched their own communications collective, Colectivo de Comunicaciones Zhigoneshi, and various documentaries, including the series “Palabras Mayores” (Elder Words) in 2009.

“Sadly, the Younger Brother has not given importance to these statements,” said Amado Villafaña, an Arhuaco filmmaker and cultural interpreter who collaborates with the communications collective. “Because among your people, it’s always: ‘Which university was it that they graduated from?’ And since they don’t have a university degree, they take this as, ‘That’s nice, they just want to talk… or they want their land back.’ But yes, the Mamos had already been telling of everything we are living at this moment.”

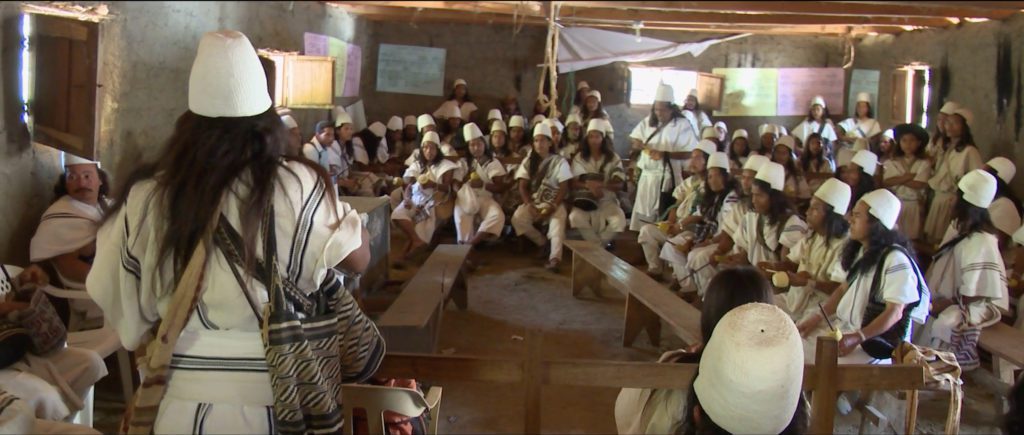

The Arhuaco, like many native peoples, practice direct democracy, making all important decisions together, in assembly. Photo: Esperanza Project – Cosmology & Pandemic

Anthropologist Felipe Cárdenas has been working with the Arhuacos and the Kogis for decades, and he remembers these predictions as early as 1980, when he began studying their divination practices.

“There is a very prophetic vision on the part of the people of the Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta. And the story they have is a story that is worth paying attention to, because it makes a lot of sense in terms of the larger society, which is quite insane in terms of its environmental management, of dealing with living beings.”

These prophecies correlate with systems of prediction of other indigenous communities, and even within Christian teachings; taken together, Cárdenas says,

“we would be seeing that indeed the times that we are living — some would call them end times, times where the different announcements of the great eschatological systems of the end of time would be warning us precisely of the need to enter into a whole cultural rethinking.”

Watch the short film, “Cosmology & Pandemic: The Body as Territory” and let us know what you think.

Reading the spiritual landscape

The Mamos begin their apprenticeship in their infancy, living in isolation and individually schooled by their elders in the ancient ways of knowing. They develop relationships with the animals, the plants, the elements, and the spiritual beings in other dimensions.

“So our Mamos, many of whom don’t know how to read or write, have the ability to read what I cannot,” says Cárdenas. “They have a whole knowledge of how to read Nature like a book, not only from an intellectual, rational way of knowing… nature is like a great text, a great library that is giving me great messages, and it also is transforming me into a wise man or woman.”

For the peoples of the Sierra, the spiritual territory that overlays the physical one is at least as important to care for, and an important part of their work is to maintain this sacred geography.

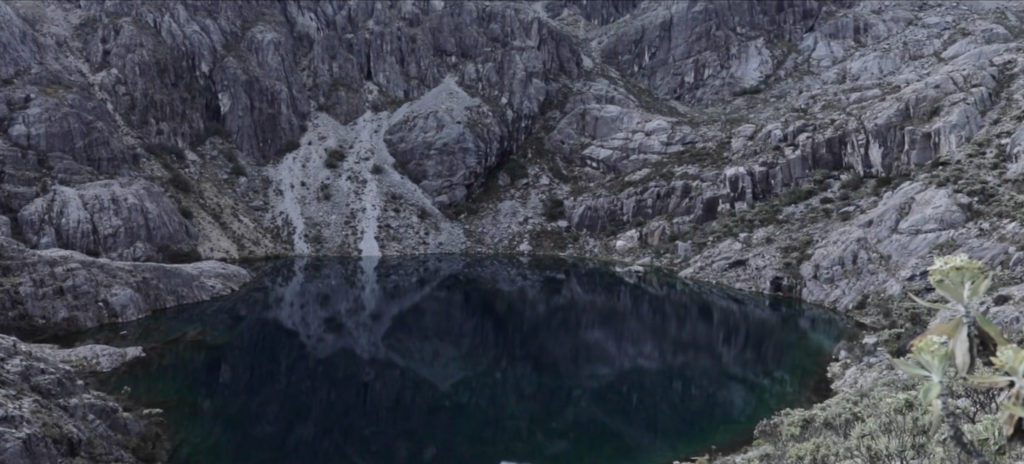

The peoples of Sierra Nevada are considered intimately interconnected with their natural environment. Photo: Esperanza Project – Cosmology & Pandemic

The Mamos’ way of healing draws on that geography, rather than focusing on the symptoms of the illness, explains Cárdenas.

“Because the scale of thought of the Mamos of the Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta is the physical territory, but it is also the spiritual territory, it is the ontological planes and folds of the territory.”

Modern society’s emphasis on Western science has eclipsed the essential spiritual nature of the Earth, said Villafaña, as well as a core reality that is obvious to the Arhuacos: that of the interconnectedness of all life.

“The Younger Brother always makes separations,” said Villafaña. “But lately the quantum physics area is beginning to recognize that everything is in everything else, and nothing is separated. And (it recognizes) the ways in which one thing affects another, right? And when that is broken, there are consequences. So I believe that quantum physics is finally beginning to approach the knowledge of the Mamos.”

The waters that come out of the springs are medicine for the peoples of the Sierra Nevada. “They should not undergo changes but remain,” says Mamo Camilo. “Do not intervene with cement, you have to protect them.” Photo: Esperanza Project – Cosmology & Pandemic

Arhuaco response to the crisis

Leonor Zalabata, Arhuaco leader and delegate for the Colombia Human Rights Commission, decries the lack of medical care in the territories.

“One of the grave problems that we have is that the public health services that a pandemic merits have been left to the private sector and we are left with the same precarious conditions that we have always had.”

Like the Kamëntšá and the Misaks, the Arhuacos have accepted the validity of the Western prevention protocols: masking, handwashing and distancing, above all. But their own protocols went much further than those of the government. They restricted their own movement to the extent possible, discouraging trips to the cities with a special payment and a 15-day isolation upon their return.

They set up their own kind of biosecurity posts at the entry points of their territory, staffed by Mamos like Mamo Elkin Antonio Villafaña. Before entering the territory, people must undergo a series of activities, beginning with a ritual cleansing of the person’s negative energy with clean wisps of cotton fibers, which are then placed in the fire. That is followed with a bath in a solution containing various plants that the Mamos have been guided to use. They must then undergo a “reparation” activity in which they give back to the Earth in a ceremonial way. And finally, they are given a medicine made from a solution of local plants – again, chosen by the Mamos — to drink.

The Arhuaco practice prevention by drinking infusions of plants from the highlands and the tropical lowlands. Photo: Esperanza Project – Cosmology & Pandemic

“When people would come up from the valley, sometimes they had the flu, sometimes a fever. But here with the plant they change, ” says Mamo Elkin. “Right here we heal them.”

The physical dimension of healing is just the most superficial level, Amado Villafaña stresses.

“For us the health of the body is not the most important thing; what guarantees the health of the body is Nature. So when there is loss of snow, loss of water, changes in the weather, it affects the crops that we feed ourselves. That is already a pandemic for us.

“The Younger Brother, when he begins to intervene in the rivers, he takes actions that cause the snow to thaw, then the land begins to get sick. It is the same as if we grab our body and begin to take out an eye, to take out a kidney, half a liver. The body is no longer going to be fine. There will no longer be that integral function .”

The most important part of healing is the recognition of nature as a living being so that the medicine can work, says Amado Villafaña.

“Because no medicine is extracted from nothing… The Younger Brother can say he invented it, but it is the product of Mother Earth. But for Mother Earth to do that goodness of hers, so that this medicine can serve us, there must be a totally different behavior towards Nature.”

Incompatible health care models

This more nuanced, multidimensional approach to health has no place in the modern healthcare landscape, according to Cárdenas, who is also a practicing homeopathic physician and healthcare scholar. He traces the sharp decline in acceptance of traditional medicine throughout the Americas to the early 1900s with the work of Abraham Flexner in the United States, a medical education reformer and politician who worked tirelessly to stamp out competing medical models such as homeopathy, osteopathy, naturopathy and midwifery that had a greater openness to traditional medicine.

In the years following the release of the Flexner Report, medical schools declined in number from 650 to 50. All but two homeopathy schools closed; 10,000 herbalists were out of business; and indigenous medicine was deleted from the standard of care.

The US medical model was quickly exported throughout the world, and an unfortunate result has been the decline of an intercultural dialog around health, according to Cárdenas, and a widespread dependency on the pharmaceutical-based approach to medicine. Young Arhuacos and Kogis go to medical school and come back to practice the pharmaceutical model, unable to relate to the rich herbal pharmacopoeia of their elders — and unable to create their own medicines, something that healers have done since time immemorial.

“They arrive in their communities to run a health center where they have to administer pills and drugs that expire, and they don’t dialog with the traditional knowledge,” says Cárdenas. “So the health care systems at the global level have collapsed because they depend on a very reductionist concept of health that doesn’t incorporate preventive elements, including how we think about illness.”

For Mamo Camilo, illness and its prevention are as straightforward as night and day. The Earth has given us plants to care for the body, as well as the water that gushes forth from a thousand springs. That water, he says, is our true mother; it nurses us the way a mother nurses a newborn baby. Altering the earth around those water sources — paving, digging, killing the vegetation, cutting the trees, damming the rivers that lead from them — all of it is a violation of the Law of Origin.

As a way of translating this basic law left by the ancestors to humanity, Villafaña maintains that

“the majority society with its rulers must begin to recognize Nature as a living being with rights. This pandemic was a warning bell for the Younger Brother, that the time has come to have a real change of attitude.”

Mamo Adolfo agrees and reinforces the profound challenge we are living as a global society.

“If we do not comply with this law (the Law of Origin), we see that this pandemic will continue to grow. We have visualized that four diseases are coming; after we pass this one, the other comes, then the other and so on until we reach four.”

“The destruction of nature produces the diseases that we see today,” Mamo Camilo Izquierdo (right) tells the Arhuaco communicator Amado Villafaña. Photo: Esperanza Project – Cosmology & Pandemic

Mamo Camilo also goes back to the standards passed down to the Mamos since the beginning of time.

“This is how it was established from the beginning and must be fulfilled, for the welfare of all, not just for people, but for the animals, those who fly and those who do not fly,” he asserts as he gazes into the flames dancing in the center of his cabin in the distant ancestral community of Ikarwa. “If the water disappears, everything dies; the birds are exterminated. Everything that walks on Earth is also exterminated. We would disappear too.

“For our own existence, everyone must live,” the Mamo continues seriously. “Only then will we have protection against disease.”

Learning the hard way

Fourteen-year-old Ati Fania Torres has learned the hard way to take those words seriously. She did not follow protocols and ended up infected with Covid.

“I was careless and I was infected by that trip. The symptoms I had were headache, muscle pain and sore throat, dry cough. I had a loss of taste and smell. I had to distance myself from my whole family. It lasted about three weeks. It was a very difficult time for me.

“The hardest part, I think, was having contact with my father, with my mother, with my grandmother. You never know if you could have affected them.“

Ati Fania Torres, an Arhuacana teenager infected with Covid, drinks an infusion of plants prepared by Mamo Elkin Villafaña, in charge of the community entrance controls. Photo: Esperanza Project – Cosmology & Pandemic

Months later, the curly-haired girl remembers the disease as a profound learning experience. Her wise post-Covid advice for other young people — and for the world in general:

“Young people should comply with the recommendations of the Mamos,” she warned. “That means taking care of nature, trees, rivers, mountains. Take care of Nature, so that she takes care of us.”