The UN’s Food Systems Summit was held last week in New York. This sounds like it ought to be a good thing, given the sense of impending crisis around the food sector. But a lot of people aren’t happy about it. There have been protests by people who say they have been excluded from the process, critical op-ed articles, and pre-summit withdrawals by some invited stakeholders.

At The Counter Lela Nargi wrote a good explainer of what’s going on:

At the pre-summit, global leaders declared intentions to forge an international road map for the future of agriculture on a rapidly changing planet. They were “expected to step up and launch bold new actions, solutions, partnerships, and strategies” to vastly improve food and ag systems. “That’s where the decisions (were) made,” explained professor Molly Anderson about the decision to protest the pre-summit. “The cake (was) baked at the pre-summit and the summit will be the celebration where they eat the cake.”

‘Tech-heavy, corporate centric’

Anderson has some skin in this game. She is a member of the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food), which has withdrawn its participation in the Summit, criticising ‘opaque methods of decision-making and a favoring of tech-heavy, corporate-centric private sector voices.’

At heart, this dispute is about competing values and visions of a food future. Anderson’s perspective is that the UN Summit is over-interested in tech food futures such as digitisation, gene editing, and precision agriculture, which “won’t help the poorest and hungriest people in the world very much, and will make the gap between the very poor and hungry and the wealthy even wider than it is now.” In contrast:

(T)he Civil Society and Indigenous Peoples’ Mechanism (CSM), which organized the pre-summit protest, favors “solutions that are resilient, community driven, and that impact the most vulnerable,” said Qiana Mickie, a member of the CSM coordination committee and former director of New York City nonprofit Just Food.

Grassroots views

The CSM is actually part of the UN’s sprawling mechanisms, an ‘autonomous space” which has 500 global grassroots organisations representing 380 million affiliated members, and which was created 12 years ago to give more voice in the policy process to smallholders, women, young people and agricultural workers.

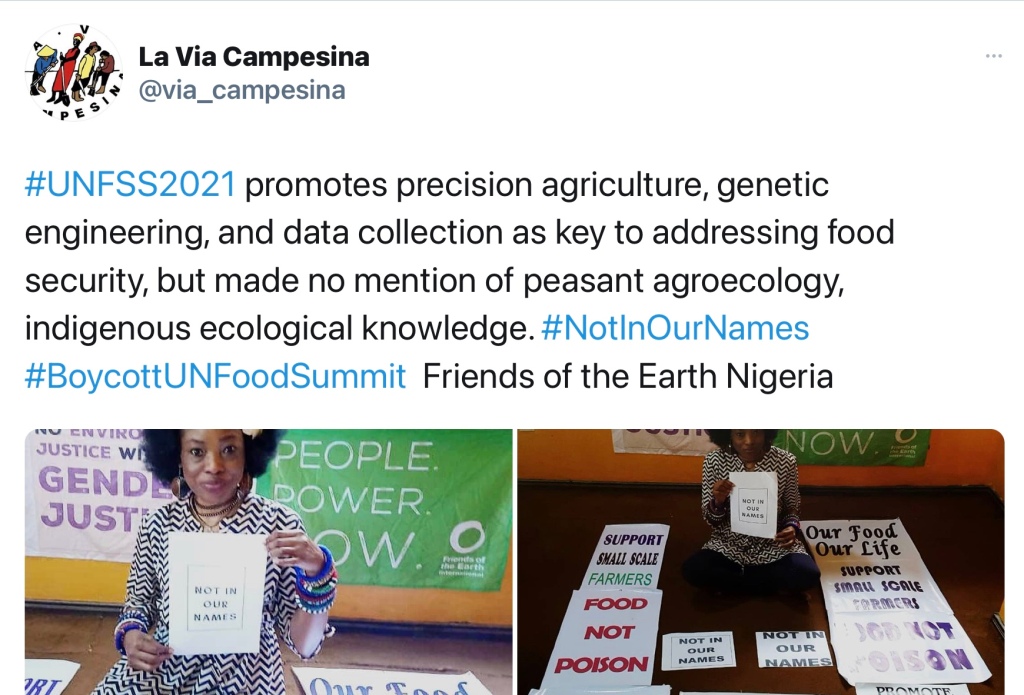

https://twitter.com/via_campesina/status/1420743375775436802?s=21

Although the Food Summit’s website now has stuff on it about civil society, the civil society critics say that this is lip service, added late in the day.

Setting the agenda

The critical issue, as always with such international meetings, is how the agenda was set:

IPES-Food’s statement alleges that organizations representing the private sector, such as the World Economic Forum, a.k.a. Davos—widely seen as a mechanism that benefits the wealthy global elite—were allowed to frame the agenda from the outset. Mickie said their goal was to focus on “investment-friendly” solutions, and that civil society was “invited to come to a table that had already been set.” CSM and a long list of supporters, including UN special rapporteurs, have claimed that the way various invitees were picked was dubious.

There’s also criticism of the Summit’s Scientific Group which is heavily freighted with economists. The World Bank’s participation is a further source of criticism, as

an actor in what Anderson and her co-authors called in a working paper the “coalescing of a market-based vision of food governance…holding the line against the food sovereignty movement.”

Wider faultlines

It’s pretty clear that this fight represents wider faultlines in the battle over the future of food. In a phrase—if slightly simplistically—this can be summarised as a dispute between actors who think you need to treat the food system as part of a wider set of systems (the critics), and actors who think that technology solutions will work (the UN, corporate organisations).

But it’s not clear that the United Nations has anything to gain by promoting an agri-food friendly view of the future. On the other hand, this may be a hangover from the success of the so-called ‘Green Revolution’ in the 1960s.

Perhaps it’s not coincidence that the Summit is led by the UN’s special envoy, Agnes Kalibata, who is president of the Alliance for Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). The Green Revolution was a technology-led programme that succeeded in increasing food output significantly. But that model, which was significantly dependent on fossil-fuels, would be impossible to repeat.

Used futures

So it’s also possible that this is just a ‘used future’, as Sohail Inayatullah has it—a set of ideas “created in some other context, but to which we are unconsciously holding on to, blinding us to other more authentic and empowering ideas of the future.”

It’s also worth comparing these competing food ideas to the pre-Summit paper published by a group of scientists in Nature.

They proposed seven priorities that reflected the scientific evidence base. Most of them focussed on the need to take a more systemic view of food production. Only one focussed on technology applications.

h/t Marion Nestle, who also has a number of articles critiquing the UN Food Systems Summit.

A version of this article was also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.

Teaser photo credit: Yara N-Sensor ALS mounted on a tractor’s canopy – a system that records light reflection of crops, calculates fertilisation recommendations and then varies the amount of fertilizer spread. By bdk, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10747049