This article was originally published on Waging Nonviolence.

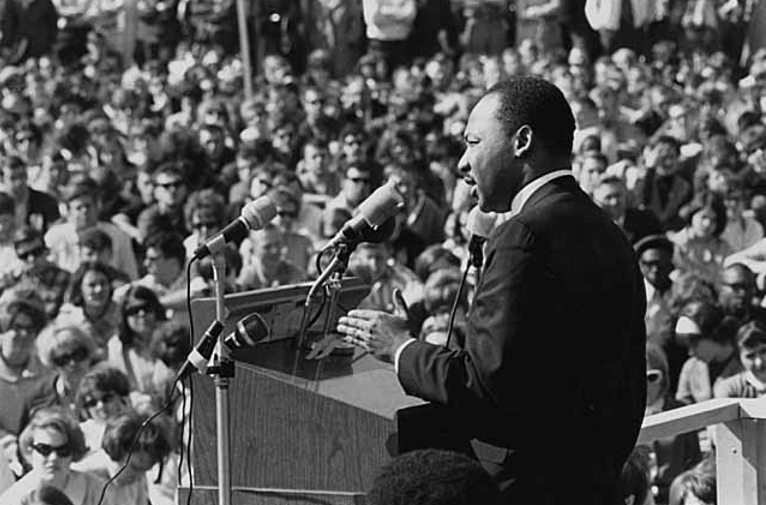

On August 31, 1967, Martin Luther King, Jr. stood before an audience of thousands while delivering a prophetic speech at the National Conference for New Politics in Chicago. Spoken less than a year before his assassination on April 4, 1968, he famously decried what he called “the three evils of society,” namely, the “giant triplets of racism, economic exploitation and militarism.”

Emerging from the fiery crucible of the civil rights movement and poised in trenchant opposition to the Vietnam War, he spoke defiantly of the need for a “radical revolution of values,” an unremitting commitment to “go out into a sometimes-hostile world, declaring eternal opposition to poverty, racism and militarism.” Highlighting some of the foremost injustices and contradictions of his time, his words were finally met with overwhelming applause, echoing the hope and indignation of communities across the globe.

“And we say to our nation tonight, we say to our government, we even say to our FBI, we will not be harassed, we will not make a butchery of our conscience, we will not be intimidated, and we will be heard.”

These words still resonate powerfully today, conveying a resolute expression of truth to power. Yet more than half a century later, the three evils identified by King have either remained stubbornly entrenched or tragically increased, compounded by a mounting ecological crisis inimical to life itself. Still, it is precisely the lingering unfulfillment of his call that adds to its historic urgency, alerting us to the inescapable need for radical nonviolent change.

To mark this year’s International Day of Peace, as the global community is called to ceasefire and non-harm, it is worth pondering the current state of King’s “evils” both to ground ourselves in existing realities and to pinpoint different possible alternatives. In the end, the simple truth is that now more than ever, we are called to the work of active hope and the ceaseless pursuit of beloved community.

Militarism

Contrary to the rosy meta-narrative of so-called New Optimists, such as Steven Pinker, conflict and violence are not on a clear-cut historic decline. Instead, despite measurable reductions in absolute battle deaths since 1946 — albeit based on arguably narrow measures — the number of internationalized civil conflicts has risen substantially over recent years, with more countries exhibiting violent conflict in 2016 than at any point in the last 30 years. In 2020 alone, world military expenditure rose to almost $2 trillion — the highest level since 1988 — despite a precipitous decline in global GDP, thus attesting to the growing influence of militarism in our time.

Alongside the endless carnage of the so-called “war on terror,” which has by now taken nearly one million lives and cost more than $8 trillion, the United States has recently adopted an official strategy of “great-power rivalry,” leading some observers to speak of a new Cold War. Couple this with associated trends in organized crime, urban and domestic violence, violent extremism, lethal technology, nuclear proliferation, frayed multilateralism, and related threats to regional and global security, and you finally end up with a far more ambiguous picture.

As I write these words, Afghanistan is spiraling into lethal chaos following 20 years of imperial adventurism — a brutal saga with deep historical roots and a stark reminder of the pervasiveness of war. In Syria, millions have been forcibly displaced and thousands led to drown in perilous voyages for refuge, forced to risk extreme violence en route to the Mediterranean. In Yemen, children comprise a quarter of civilian casualties, with thousands killed since 2018 and millions facing the threat of war-induced malnutrition. Yet as devastating as these figures are, they represent only a fraction of militarized violence worldwide. Indeed, similar dynamics occur in parallel conflicts across the globe, further reinforcing the need for radical transformation.

To quote King, this destructive “arrogance of power” must be abolished, for “a true revolution of values will lay hands on the world order and say of war, this way of settling differences is not just.”

Poverty

According to recent estimates, last year witnessed what even the World Bank has described as an “unprecedented increase” in global poverty, with pandemic-induced stressors leading to an additional 97 million people living under extreme poverty. Bracketing the contested status of this metric, this marks the first time in a generation that such a setback has occurred, totaling an estimated 711 million people this year — a figure that swells exponentially under revised measures, such as the ethical poverty line or multidimensional poverty index.

Despite a projected rebound on the horizon, as much as half of the recent increase could remain permanent over the long term, with the deepest and most enduring impacts set to occur in low-income countries and sub-Saharan Africa. These unsurprising facts, while reinforcing existing fault lines of global inequality, also exemplify one of the defining features of modernity, namely, that of a hegemonic order founded on the structural violence of inequity — as currently reflected in the bio-political rift of vaccine apartheid.

Although subject to national and regional variation, inequality both within and between countries constitutes one of the core drivers of contemporary development, with the bottom half of humanity owning less than 1 percent of existing wealth and the top 1 percent owning almost half of it. During the pandemic alone, global workers lost an estimated $3.7 trillion in earnings while the world’s billionaires grew their fortunes to a record $10.2 trillion, leaving women and young workers most susceptible to loss. Instead of increasing equality, what we see is the creeping sedimentation of global plutocracy.

As in King’s time, the poor are “still perishing on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity,” leading to a crisis of “bewildering frustration and corroding bitterness.” The only solution, therefore, is to end exploitation, democratize power and reimagine access to equitable social supports.

Racism

“We have deluded ourselves,” argued King, “into believing the myth that capitalism grew and prospered out of the Protestant ethic of hard work and sacrifice. The fact is that capitalism was built on the exploitation and suffering of Black slaves and continues to thrive on the exploitation of the poor — both Black and white.”

To this we must add the genocidal erasure of Indigenous peoples, the extractive ruination of nature, the colonial plunder of stolen wealth, and the exploitation and suffering of additional groups across the planet.

In each of these instances, racism has constituted a core element in the dialectic of modernity, continuing in this manner up to the present day. As far back as 1903, W.E.B. Du Bois observed that “the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line.” Writing over 50 years later, King identified racial and economic injustice as “inseparable twins,” arguing in 1967 that “the problems of racial injustice and economic injustice cannot be solved without a radical redistribution of political and economic power.”

This insight remains equally valid today, with racism, xenophobia, and the “creeping fascism” of authoritarian populism deeply intertwined with hegemonic systems and forms of power. According to a recent Gallup poll, race relations in the United States are currently at their worst in decades, coinciding with a widening racial wealth divide and correspondingly unequal conditions of livability. Globally, the pandemic has resulted in disproportionate impacts on marginalized racial and ethnic groups, as well as increased reports of racial and xenophobic violence. Yet these trends are nothing new, reflecting longstanding patterns deeply ingrained in the colonial matrix of power.

In the words of King, this merely represents “the surfacing of old prejudices, hostilities and ambivalences that have always been there.” As in generations prior, “racism is still that hound of hell which dogs the tracks of our civilization,” calling for an anti-racist, decolonial politics responsive to emergent complexity.

Ecocide

Several years after the publication of Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring”, which helped spark the modern environmental movement, King noted in his final Christmas Sermon that

“it really boils down to this: that all life is interrelated. We are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied into a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Although referring in this instance to globalization and the shared fate of nations, his suggested ethic of interdependence speaks directly to the mounting ecological crisis of our time.

As was recently affirmed in the Sixth Assessment Report of the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, it is “unequivocal” that anthropogenic activity has resulted in “widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere,” leading to increasing weather and climate extremes in “every region across the globe.” According to leading Earth system scientists, the “safe operating space” for humanity has now been breached across four of nine “planetary boundaries”, namely, those of climate change, biodiversity loss, land-system change, and nitrogen and phosphorus loading. Associated with this are worsening droughts, floods, heatwaves, wildfires, tropical cyclones, and related weather extremes, as well as accompanying impacts on health, safety, livelihood, food and water security, and other determinants of wellbeing.

Such impacts are highly uneven, with those least responsible for the crisis subject to the most adverse outcomes. Viewed through the lens of interdependence, this has generated a vicious cycle whereby already-vulnerable populations suffer disproportionately and are thus rendered more vulnerable, hence resulting in increased disproportionality. Furthermore, the accompanying impacts on more-than-human-life are similarly alarming, with worsening climate shocks and ecosystem degradation capable of triggering sudden, irreversible biodiversity loss.

At present, these mutually reinforcing processes are driving the sixth mass extinction of life on Earth, with many calling for the recognition of ecocide as an international crime on par with genocide and crimes against humanity. Yet as laudable as these efforts are, it must be recalled that ecocide is itself symptomatic of a deeper nexus of underlying forces, namely, the ruthlessly extractive logic of fossil capitalism and the globally dominant paradigm of industrial growth.

The three evils identified by King are integral to this crisis, with militarism, environmental racism, and intersectional inequality featuring centrally in the “slow violence” of ecocide. Hence, what is required is degrowth, a sweeping just transition, and a deep reimagining of our place in the web of life.

Bending the arc of history

It is easy to despair when confronted with such stark realities, and this is entirely natural given their overwhelming gravity. However, despair signifies only one half of the equation of resistance, for as King himself once noted, “We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope.” This is especially true when considering the tangled ravages of militarism, poverty, racism and ecocide, which together demand an inexhaustible surplus of hope — hope in the eternal possibility of change and our capacity to nurture the life-affirming truth of beloved community. Yet in order to do so, we must be willing to accept the risk of “creative maladjustment” to the world as given.

Instead of militarism, we can strive for an alternative global security system rooted in common security and a global peace economy; instead of poverty, we can strive for economic democracy and the protection of the commons; instead of racism, we can strive for a decolonized future rooted in the ethos of pluriversality; instead of ecocide, we can strive for a just transition to a truly ecological civilization. These and kindred visions articulate the possibility of a radically different future, in pursuit of which we are called to more than just critique. Drawing on the Gandhian legacy that so deeply inspired King, we are also called to the ongoing advancement of a “constructive program,” that is, nonviolent action oriented toward the creation of positive alternatives.

Already this is happening across the world. As civil resistance scholar Erica Chenoweth recently observed, 2019 witnessed “what may have been the largest wave of mass, nonviolent antigovernment movements in recorded history.” Globally, movements such as Land Back, Black Lives Matter, La Via Campesina and the Climate Justice Alliance continue to demonstrate the insurgent power of creative mass resistance. Likewise, the pandemic has practically exploded the myth of neoliberal triumphalism, revealing the true depth of our interdependence and proving once and for all that rapid change is possible, even at massive scales, if only we can muster sufficient political will.

Guided from below, these conditions have the potential to bend the arc of history. Hence, instead of waiting for crisis to strike, we must be relentlessly proactive in our quest for peace. Precisely what this means is for each of us to discover, but one thing beyond doubt is the necessity of the quest itself. As King declared in his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech,

“Peace through nonviolent means is neither absurd nor unattainable. All other methods have failed. Thus we must begin anew.”

In this spirit, let us set forth with truth, love and justice as our guides, mourning the cost of needless harm while nurturing the promise of radical transformation.

Let us move, in a word, from despair to beloved community.