Preserving food is not just ‘cooking’; preserving food requires that you think about the future. Hence why growing and preserving food can be a window into planning a new future.

Consumerism isolates & disconnects: The media hypes the desire for this lifestyle, while we struggle to obtain the cash to buy it; and in this process its hyper-individualism turns our focus inwards, isolating us from other people and the natural world.

From climate change to resource depletion, the systems which underpin that lifestyle are failing (though if you are in the ‘precariat’, arguably that happened twenty years ago). Finding a solution to the trap of affluence, or of state-dependent poverty, requires the same practical response:

Opening-up to new habitual methods for living.

“It’s a connection thing…”

Our wild garden, 2019

This post started out as a simple idea: To document how I tend, pick, store, and use the raspberries that grow in the garden. It’s a thing I do as part of daily life. It’s not a chore that needs doing; it’s a release from the ‘dead’ energy of consumerism, to engage instead with the positive, natural, life-giving energies of own-made food.

OK then, it’s not that simple! Thing is, preserving food is not cooking! It requires that you think about your future. This is about raspberries, but it could equally be about seed sprouting, growing lettuce in boxes, or foraging (which is what the next post will cover).

One of the most powerful methods to learn something is by repetition: Times tables were once drummed into children at school; musicians endlessly practise scales to train their fingers where to go; craftspeople repeat the same actions over years to perfect their skill at making things.

Making people repeat actions is a way to condition their instinctive response thereafter.

Now apply that to the consumer lifestyle:

- Go to work to earn money – or submit to the deliberate humiliation of the welfare system – to get an insufficient amount to live the life you are ‘sold’ in the media;

- Use the money to pay for daily needs;

- As required by that lifestyle, consume the food you see advertised, or that is the only food you can affordably buy;

- Go back to step 1.

What if you substitute that with a different kind of activity? Like making raspberry pies?

Breaking the repetitive conditioning that the modern lifestyle enforces doesn’t require legislation. You don’t need permission from your ‘leaders and betters’. It only requires that you take the time to learn and express that ‘skill’ – repeatedly – in your daily life.

All you need do is learn a practical skill, that reinforces your economic independence and ecological well-being, and that can be easily repeated. Start small, with a single action; then improvise to create new opportunities – and so create the life you want.

‘Harvest new moon’

The full moon nearest to the Autumn Equinox is called the ‘Harvest Moon’. I’ve always found the new moon before that to be more significant, as it’s when I start to spend a lot of time outdoors foraging – mostly blackberries or nuts to store for use over the Winter. Likewise, it’s when the ‘forage’ from our small, wild garden demands the greatest effort too.

Blackberrying by the

New Harvest Moon, 2019

I’m so lucky: For me this is not a ‘self-taught’ activity. I was brought up in a family where foraging, growing food, and cooking own-grown food, was an habitual practise; and had been so for generations.

The experience of doing this, in the same location as generations of my family before, adds yet another level of ‘energy’ to this activity. It represents not just a practical middle-digit to the power of consumerism; it’s also a practical expression of the inherited life-skills of my ancestors, living in this place.

Those skills, and the space to express them, have shrunk over the last century. Access to land has been curtailed by changing agricultural methods. The allotments around the town have been sold and built-over. All I have is a small, badly located garden; and access to what countryside remains within the arable prairie that erased local fields and hedgerows in the 1970s. Nevertheless, I perpetuate my indigenous culture, because I can.

Likewise, others could collectively create a new ‘free’ culture in the space available to them (whether they have ‘permission’ or not). Again, just like the individual can learn a skill, when that is practised as a community, we create a common culture; and a physical space to practise that culture in. All it requires is the will to undertake these actions ‘habitually’, as part of our daily lives.

If those who believe they are ‘in control’ don’t like it, then the issue becomes our freedom to live in this land, versus their presumed control of the resources the land provides.

‘Time-shifting’ nutrients

Traditional human culture is not free of constraint; it is formed by the land they live within. It defines how that culture can naturally grow, harvest, and preserve foods.

All traditional societies by necessity grew and harvested food to live. The further north you go, the more that preserving food is an integral part of culture – in order to survive the more extreme depths of the Winter. Hence in Italy foods were air-dried; in Britain foods were smoked or pickled; and in Scandinavia food were buried and fermented.

The attraction of consumerism is that all this effort is made redundant. You just go and buy the same food, whatever the time of year. Just ignore the small detail that this lifestyle is devouring the planet to keep itself running.

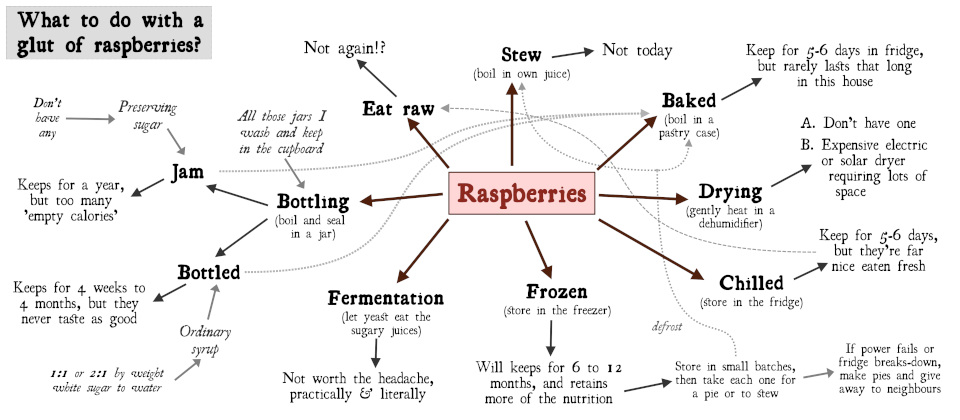

At the simplest level, all food preserving does is ‘time-shifting’: Taking food which you can’t possibly eat today; and doing something to it to keep as much as its nutrition as possible available in the future. Practically that is just a set of choices (see diagram below).

It may be that you have an ambition to try all these choices in the future; but when the food is in your hands, you have to focus on doing something to preserve it right-away, before the food spoils. In which case, just choose the one that’s the most do-able.

Break the ‘false convenience’ of consumerism by applying a large dollop of DIY, and it creates a measure of economic independence. More importantly, it re-connects us to those natural cycles of the Earth; and the constraints it enforces upon our lives as living beings within this landscape. It also allows us to sense those ‘inconvenient’ things that consumerism is doing to the land in the name of ‘progress’ – and so work to change them.

Food preservation is ‘cooking with a plan’

When humans stopped roaming and settled down, they had to store and preserve food. When they were nomadic, they probably did this using methods like smoking or air-dying. But with settled agriculture, based on annual crops, they had to plan ahead to manage their supply of food across the year: They had to have ‘a plan’.

The point about cooking is that it concentrates on preparing food to eat right away.

The point about preserving foods is that it’s not just a matter of learning a technique. You need ‘a plan’ for using those skills: What you want to store; how long you want to store it; and how much to store to meet your needs.

Every food has its set of preserving options. I won’t go into those in detail; there are already so many books and web sites out there already. What few of those books and sites talk about, though, is ‘the plan’; the set of options you have to preserve food, and how you want to use them to store it.

Mapping the options for preserving raspberries

Our raspberry plants are absolutely brilliant. They fruit from May to July, and after a short break, we get a second crop from September to early October. At least once a week we can pick up to a kilo, only half of which we can eat immediately – so we need ‘a plan’. That gives a set of options every time we pick raspberries:

Eat raw. Simple. Easy. The thing is there is only so much you can eat of the same crop before it gets boring; and to eat a balanced diet you need to have variety.

Stewing means boiling the fruit in its own juice. This kills any yeasts or organisms that would make it spoil, and the ripening enzymes which would otherwise make it rot. This extends the ‘shelf life’ in the fridge.

Baking has many opportunities, from pies to cup cakes. Like stewing, it makes the fruit last longer by halting the ripening process.

Bottling involves boiling the fruit with a preservative, the most common being sugar, so the fruit can be sealed in jars. There are three options here:

Jam-making involves stewing the fruit with a large amount of sugar. Raspberries need ‘gelling sugar’ with added pectin to make it set. This will easily keep in a cool cupboard for a year – though the down-side is you’re using as much sugar as fruit, which adds lots of empty calories.

Another option is bottling in syrup, using less sugar compared to jam. The trade-off is that this may only preserve the fruit for a few weeks rather than months.

The final option is to pickle the fruit with vinegar to make chutney – which obviously ruins the flavour of raspberries.

Freezing food also interrupts the natural ripening process, as well as killing or making bacteria go dormant. Unlike boiling, though, it doesn’t destroy as much of the nutrition that the fruit contains. Provided the fruit goes straight into the freezer after picking (with a quick sort or rinse to remove dirt) it will last for up to a year.

The main risk with freezing is, what if the freezer breaks-down; or what if you lose your power supply? That’s a risk you have to judge; and in the worst case, quickly bake all your frozen food and share with neighbours.

Fermentation involves putting the fruit in a jar with yeast to turn it into wine – though theoretically you could then turn the alcohol into vinegar (as many inadvertently do). Seriously though, it’s a lot of effort for a product that has no nutritional value.

Chilling food is a method that has been used for thousands of years, long before the electronic fridge was invented. While it slows the ripening process it can’t stop it, so at best you’ll keep the fruit for a week or so.

Finally, drying is another option that’s been in use since prehistoric times. Drying removes the water from the food, stopping the ripening process and killing bacteria. The problem (in England) is that this requires an expensive electric dehumidifier, or the space to build a solar_dryer – neither of which I have.

Over the years, with the exception of drying, I’ve used all these preserving options. When presented with a big bowl of fruit, what matters most is estimating what you can do in that moment. The point is not that having these skills allows you to save money, or to eat your own food: It’s that in any situation, you carry in your head the skill that is most appropriate to use there and then.

Half in a pie, half in the freezer

What will I do with the almost 800 grams of ‘organic’ raspberries that I have today? (which would currently retail at about £13-£14): Half in a pie; half in the freezer.

The bottom draw of the freezer is devoted to fruit. It’s almost half full; by the end of the month will be rammed full, with the surplus shoved into the draw above. The pie today will last for half-a-week or so; and what I put in the freezer will be a ‘future pie’, that will also last about the same amount of time.

In an older video I prepared blackberry and apple pie filling, then made pies, then froze the entire pie. That’s because apples are one of those fruits that don’t respond well to cooking and chilling. Far better to make a ready-to-cook pie, freeze it, and then cook the whole pie from frozen. If we are given a carrier bag or more of apples in one go, that is probably what will happen to them.

The raspberries need a rinse to get rid of any dust and insects; and perhaps pick out anything that escapes that. I put half in a plastic container and put it in the freezer. A day later I run warm water over the bottom of the container, allowing the block of frozen raspberries to drop out into my hand. That gets put in a bag in the bottom of the freezer, and I can reuse the plastic container.

I could put the raspberries that remain in a pastry case and bake them. The problem is these raspberries are incredibly juicy. What I’m going to do is cook them quickly with some semolina or ground rice to soak-up all that juice. While that is happening I blind-bake a pastry case in the oven. Then I fill the pastry case, put the lid on, and bake it.

A problem people have when making pastry is judging exactly how much flour to use to make just enough pastry. Often this means there’s not quite enough, or you have a little bit left over.

I say do the opposite: Make lots of pastry, and then make biscuits with the left-overs.

When I bake sweet or savoury pastry I always make too much for what I need. When I’ve finished making the pastry case, anything left over gets rolled flat once more, and I cut biscuits from the dough.

With savoury pastry, you might spread a thin layer or miso or Marmite over the surface, and perhaps sprinkle pepper. Then roll it up, roll the tube out flat again, and then cut biscuits from it. It makes far more of a savoury snack than just the pastry alone.

Put the biscuits on a try at the top of the oven, above the pie, and perhaps leave them there after the pie has baked – until they start to go brown.

The product of my labour: A raspberry pie & a dozen biscuits

After my couple of hours of pottering around the kitchen and garden I have: A large raspberry pie, that will keep the family going for a few days; and a dozen biscuits, which will keep them snacking for a couple of days without shop-bought products.

What I hope I have shown here is not so much a recipe, but the outline of ‘a plan’. Preserving food is not cooking: It might look the same, but when you preserve food you have to think about the future – to plan for how much food you need, and how much you might be able to provide. It’s that foresight that allows you to have greater certainty, and so greater independence about other aspects of life generally.

To bring this full circle, the power of consumerism is to make the alternatives ‘less convenient’. But what if you ‘habituated’ the planned alternatives that created a more certain future? What if you found ways to keep extending that process to cover more of your needs? What hold would consumerism, and industrial society generally, have over your lifestyle then?