From the houses we live in to the food we eat and the education we receive, living a good life requires materials and energy. For many, this means an increase in wellbeing requires an increase in resource use.

This necessity has been used by some commentators to argue that eradicating poverty is at odds with the need to reduce emissions and tackle climate change.

Yet, despite the clear importance of linking the two goals of poverty eradication and climate action, climate mitigation scenarios rarely consider the energy needs for human wellbeing.

In our new study, published in Environmental Research Letters, we look at the current status of multiple material and service deprivations and calculate the energy required to provide “decent living standards” (DLS) to all – including to build the infrastructure to reach those that still lack them.

We find that, on a global scale, supporting DLS for all would require roughly a quarter of projected world energy demand by mid-century, though the share would be larger in regions with the highest poverty levels.

These figures also apply to scenarios where energy demand growth is squeezed to achieve ambitious climate goals. The overall implication is that the energy needs for poverty eradication are unlikely to pose a threat for climate mitigation.

Moreover, if the equitable provision of basic services is prioritised over affluence, then less energy demand growth would be required to meet human wellbeing and the consequent burden of climate mitigation is reduced.

Decent living standards

Attempts to quantify the material conditions needed for basic human wellbeing are a relatively new field of research.

In our new paper, we looked at minimum threshold requirements for DLS across a range of domains including shelter (housing, cooling, heating), nutrition (food, food preparation, food conservation), health (water, sanitation, health care), socialisation (communication and information, education) and mobility (transport infrastructure).

For all of these dimensions, we quantify the requirements for wellbeing on a societal, community, and household and individual level.

For instance, health care and road infrastructure needs may be met at a societal level, schooling on a community level and access to clean cooking at a household level.

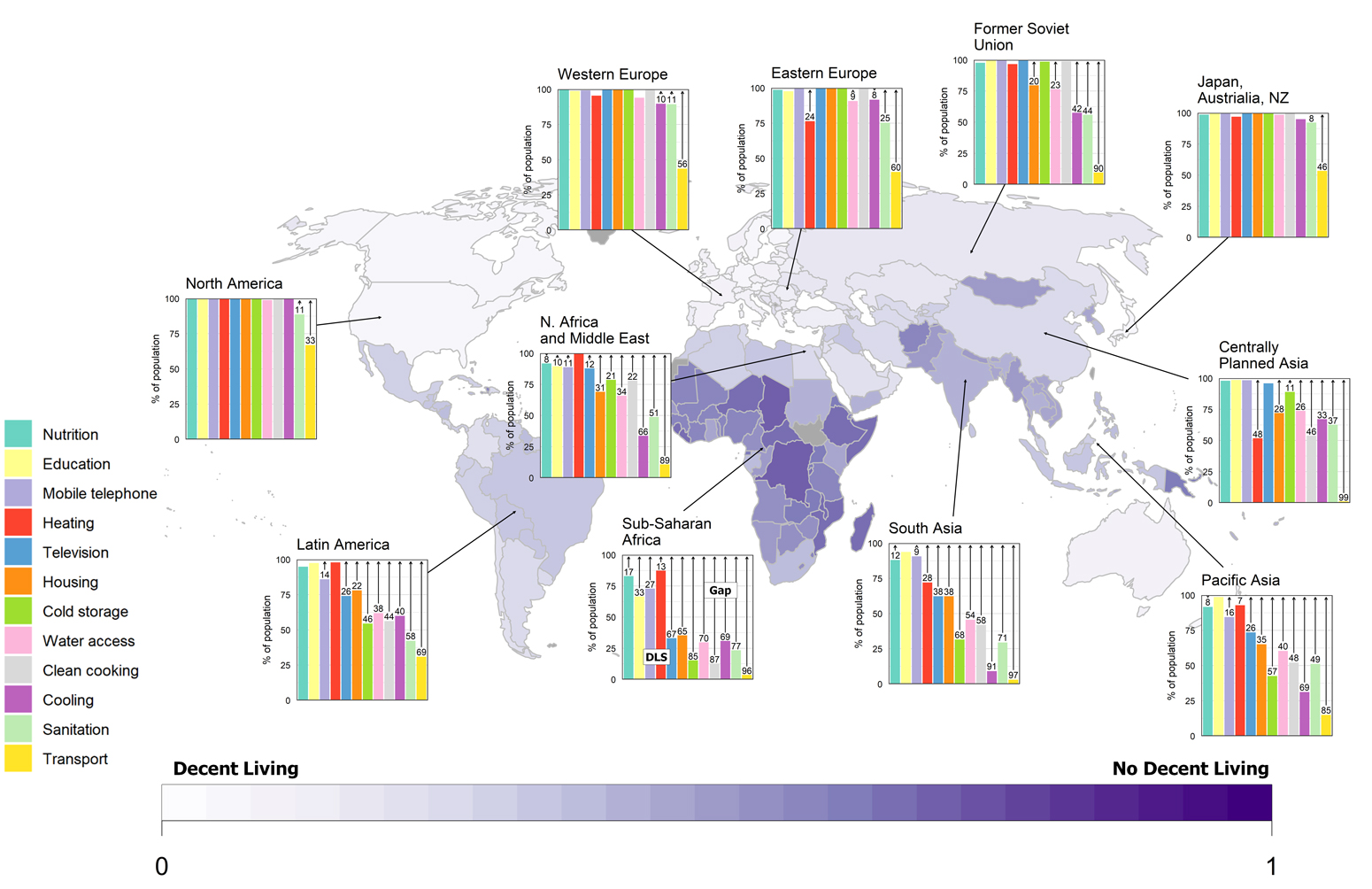

Using data from national household surveys, World Bank development indicators (WDI) and the Demographic and Household Surveys (DHS), we characterise the gaps in each dimension of DLS around the world.

Our data shows that people in sub-Saharan Africa are generally living far below decent living standards, with parts of Asia also seeing large deprivations for some dimensions.

This is shown in the figure below, with darker shading representing a lack of decent living and pale shading indicating the material conditions for wellbeing are generally available.

For each region, the bar charts below show the population share with decent living standards in each dimension and the numbers indicate the proportion of people going without.

Map showing the average decent living standards (DLS) deprivation indicator for each country from zero (all thresholds met, white) to one (no thresholds met, dark blue). The inset charts visualise the regional average share of population living below decent living standards (gap, in white) alongside those with decent living standards (coloured bars) from 0 to 100%. Source: Kikstra et al. (2021).

Eradicating poverty

Our baseline data confirms that providing DLS for all would imply an increase in material and energy use, particularly in the Global South.

We found that filling the gaps in basic provision would require an extra 68 exajoules (EJ) of energy on a global basis, or about another 5 gigajoules (GJ) per person on average.

These figures can be compared with the current total global energy demand of more than 400EJ and the average per person of about 55GJ.

While this increase appears relatively small at a global level, it would mean a very stark break with recent trends in many poor countries.

For example, energy growth in sub-Saharan Africa has generally only matched population growth in the past two decades, meaning energy consumption per capita has remained flat.

In order to provide DLS for all by 2040, energy provisioning for basic needs in some poor countries would at least have to double by 2030 and triple by 2040, even if all energy growth were directed solely towards poverty eradication efforts.

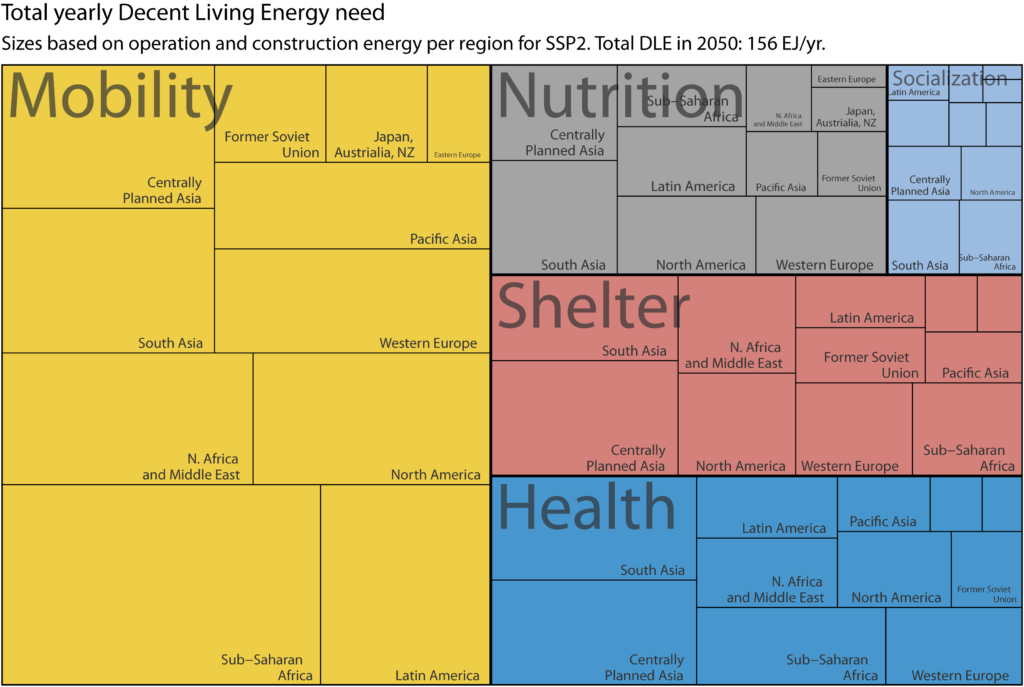

The construction of new buildings and transport infrastructure are the biggest factors in providing new services. This construction energy, at about 12EJ per year, is, however, much smaller than the annual needs to operate services on an ongoing basis.

The figure below shows the annual energy requirements to support decent living standards for all, broken down by type of basic need (coloured areas) and by region.

It shows that mobility comprises almost half of the energy, nutrition and shelter together account for about 30% of total needs and health for a little under 20%.

Total yearly energy needs to support decent living globally, by type of basic need and region, based on building and operating the infrastructure required. Source: Kikstra et al. (2021).

Although there are global minimum thresholds, the energy required to satisfy basic needs varies with climate, culture and existing provisioning systems.

A car-dominated society would need much more energy to provide the same amount of travel than one reliant on public transport, for example. Cold climates require more energy than do hot climates to maintain a comfortable indoor temperature.

As a result, we find that the total DLS energy needs range from ~9-36GJ/yr per person, with the lower end typically required in tropical and subtropical low- and middle-income countries, and the high in rich countries in temperate regions.

This range is similar to other recent work. It is remarkable that this total amount is similar to the 32GJ/yr that scientists estimated way back in 1985.

Affluence drives growth

Overall, sustaining DLS for all in mid-century would only require a fraction of current global energy use, suggesting this is not a fundamental barrier to poverty eradication.

However, most energy growth expected over the coming decades serves increasing quality of life and affluence, rather than the basic needs to enjoy DLS.

Energy demand growth through rising affluence stems from higher levels of services in all domains – bigger houses, more travel, more consumer goods – but also more energy-intensive products to provide these services.

The affluent drive SUVs and fly for vacations, for example, while lower income groups tend to use more public transit and travel more to local destinations.

Shared resources generally use fewer resources than individually owned goods. Thus, services that support basic wellbeing, such as water, sanitation, education and healthcare, tend to be less energy intensive than large homes and private cars.

For this reason, development policies targeted towards basic wellbeing could reduce overall energy demand growth – and, consequently, GHG emissions.

It is, therefore, important to distinguish between affluence and basic needs in future energy demand scenarios, to identify the climate implications of lifting people out of poverty.

Yet this distinction is frequently left out of the climate mitigation scenarios that are an important input for the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Inequality obviously matters a great deal for reaching the sustainable development goals in themselves, but also matters directly for climate policies and climate impacts.

Some types of inequality – such as gender and education – are covered in the underlying shared socioeconomic pathways used by the IPCC. However, often these inequalities do not interact with other elements of the models used to explore emissions and mitigation.

Generally speaking, as we explore in a forthcoming paper, climate mitigation analysis still relies on macroeconomic relationships with energy – generally meaning rising GDP drives higher energy demand – even though GDP is a poor indicator of wellbeing or basic services.

Any such analysis cannot account for inequality within countries or identify synergies between equitable development and climate goals in the Global South.

Simply assuming higher levels of wellbeing can only be reached at levels of resource use seen in the US or Europe ignores a large and growing body of work that shows high gains in human development are possible with low levels of energy growth.

Poverty and mitigation

Our research shows that current global energy consumption is already, in principle, sufficient to provide everyone with a decent life. But this will happen only if there is a stronger focus on providing the energy to serve basic needs rather than growing affluence.

For instance, while global energy supply under pathways that limit global temperature increase to 1.5C is more than enough to provide for basic needs, as well as some affluence, projected DLS energy needs for some regions and countries can go up to or exceed half of the total. (Faster energy efficiency improvements would reduce this ratio.)

Together, this means that while eradicating multidimensional poverty is compatible with ambitious climate targets, it does likely require a shift towards more equitable energy, climate and development policies, both within and between countries.

Kikstra, J.S. et. al., (2021). Decent living gaps and energy needs around the world, Environmental Research Letters, doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac1c27

Teaser photo credit: By Djembayz – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27940740