Half a dozen mining proposals to extract low-quality coking coal in the eastern slopes of the Rockies don’t make any economic sense and shouldn’t be allowed, say two Alberta coal experts with more than 70 years’ experience in the industry.

In separate written submissions to Alberta’s Coal Policy Committee this summer, a retired geologist and a mining engineer testified that the market value of metallurgical coal seams in Alberta will never be able to compete with the quality of coking coals in B.C.’s Elk Valley mined by Teck Resources.

“These speculative mines don’t meet the requirements to be viable by any economic analysis,” said Cornelis Kolijn, a semi-retired process mining engineer with extensive experience in metallurgical coal, coke making and product development around the world over 40 years.

The Kenney government reluctantly created Alberta’s Coal Policy Committee after it initiated a political scandal by abruptly rescinding long-standing coal development rules in 2020 without public consultation.

Those rules prevented mining in much of the eastern slopes, but Australian coal miners learned of their removal before Albertans did.

Public outcry then forced the government to reinstate its coal policy and create a five-member committee to investigate the future of coal mining in the eastern slopes.

All summer long it has been hearing submissions from Albertans, First Nations, environmentalists, ranchers and Australian coal companies. It will make its recommendations in the fall.

Kolijn, who worked for Teck Resources from 2001 to 2018 specializing in Elk Valley’s product development and applied research and development related to the international steel industry, explained that high-quality steel mills in Asia only pay top dollar for prime coking coals.

But the half dozen mines that Australian speculators have touted as a great deal for Alberta’s economy “won’t make that cut. That’s why Teck Resources isn’t there.”

The Canadian mining multinational operates four metallurgical coals mines in B.C.’s Elk Valley on the western side of the Rockies.

But Teck has played no role in the controversial rush by Australian penny stocks and two billionaires to develop mines along Alberta’s eastern slopes.

Kolijn, who has worked for the coking coal industry and integrated steel mills around the world including Australia, said open-pit coal mining closed in the eastern slopes during the 1960s and ’70s for a good reason.

Japanese steel mills forced the closures of the Tent, Grassy, Vicary and Adanac mines “due to inadequate quality and low-market value of their metallurgical coal, combined with increasing quality requirements for the modernizing steel industry.”

“The Japanese are a very polite people,” Kolijn told The Tyee, but even they called the coal from the Crowsnest Pass “shit coal.”

According to one source in the Crowsnest Pass, the Japanese even dumped one shipment in the ocean rather than use it in their blast ovens to make steel.

After surface mines in the pass shut down, the industry started to develop and value higher-quality hard coking coal deposits in nearby Elk Valley.+++++

In recent years Australian speculators, encouraged by the Kenney government, have expressed interest in reopening Alberta’s abandoned sites or developing new open-pit mines in critical mountain watersheds in the eastern slopes.

But available coal quality data indicates that coal seams on the Alberta side are so uncertain and variable that, if approved, these mines would operate only for a few years, go bankrupt or close whenever global prices collapse, testified Kolijn.

“Alberta’s eastern slope mining projects appear to be mostly speculative, promoted mostly by penny-stock companies,” he told the five-member committee.

Kolijn also told the committee that it is unlikely these penny stocks would have the funds to properly reclaim their mines, let alone control selenium pollution — a chronic liability that has already cost Teck Resources more than $1.2 billion in mitigation measures in the Elk Valley.

Kolijn added that proposed Australian mines in the eastern slopes would likely experience the same fate of lower quality metallurgical mines in northern B.C.

Between 1999 and 2016, the Willow Creek, Brule and Wolverine mines repeatedly opened and closed and went through three successive owners due to marginal quality coals and volatile market prices.

None of the mines ever generated the revenue, jobs or royalties they promised during public environmental hearing.

Willem Langenberg, a 77-year-old retired government geologist who worked for the Alberta Geological Survey for 34 years, also portrayed coking coals in the Crowsnest Pass as poor and uneconomic compared to Elk Valley coals.

In his presentation, Langenberg noted that coal reserves in the eastern slopes are not only smaller but much more variable than those in the Elk Valley in B.C.

He warned the committee that the Grassy Mountain coal project, which authorities rejected as not being in the public interest this summer, would end being “a typical swing mine (like Grand Cache), operating when prices are high and shutting down as soon as the price drops.”

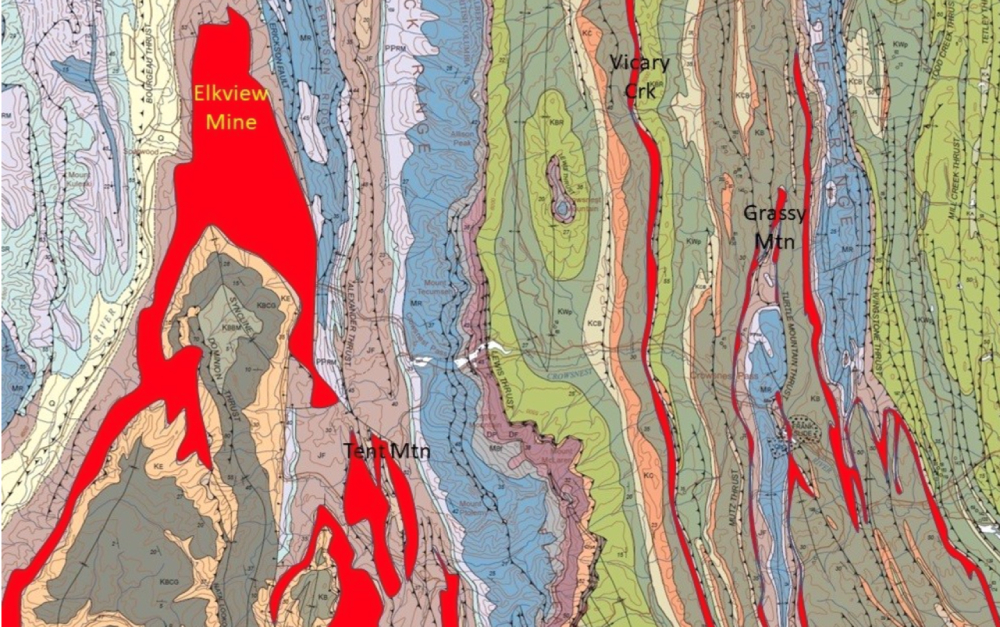

Langenberg also presented the committee with a map showing how a 600-metre-thick coal bearing formation in B.C.’s Elk Valley diminishes to 100-metre-thick deposits in Alberta’s Burmis-Blairmore area.

This map submitted by geologist Willem Langenberg to the review board shows in red the difference between sizes of coal deposits in the area of BC’s Elkview mine and where the Grassy Mountain mine was proposed in Alberta.

The quality of coal in the Elk Valley explains why Teck Resources has four active mines producing around 25 million tonnes of product a year and has reserves for 25 years of mining, said Langenberg.

In contrast, the coal reserves of the Alberta’s Crowsnest Pass area equal only 17 per cent of the reserves in the Elk Valley.

“Alberta’s coal resources are a risky source of coking coal,” concluded Langenberg.

Langenberg told the committee, “The Crowsnest Pass might be better served by concentrating on alternative industries such as tourism, recreation and renewable energy.”

During federal hearings on the Grassy Mountain project, local residents also testified that coal quality in the region was intermittent and sparse.

Fran Gilmar, whose husband once worked a surface mine on Grassy Mountain in the 1950s, wrote, “There is no high-quality coal in Grassy Mountain.”

She said the claims made for the proposed Benga Mine are similar to those made when Western Canadian Collieries made a run at mining there, “but the quality of coals did not meet up to expectation.” The mine closed in 1960.

The globe’s hard coking coal mining industry can include some highly speculative plays and questionable claims about ore quality.

Queensland-based Riversdale Resources sold the undeveloped Benga Mine in the Crowsnest Pass to Australian billionaire Gina Rinehart in 2019 for $700 million.

But before then it operated under a different name: Riversdale Mining. In 2011 it sold a new coking coal mine site in Mozambique to mining giant Rio Tinto for $3.7 billion.

Riversdale Mining had claimed the mine would produce “the lowest cost coking coal in the world.”

Rio Tinto’s senior management ignored warnings by its technical committee that the mines coking coal reserves were “optimistic.”

The company later discovered that the ore quality was not as advertised in quality or volume and that infrastructure for transporting the coal by river barges wasn’t possible. At the same time, commodity prices crashed.

As a result, Rio Tinto later sold the mine site in 2014 to an Indian steel making corporation for $50 million. Several Rio Tinto executives resigned.

One Riversdale executive later told Fairfax Media that Rio Tinto blew a great opportunity and was to blame for the write-down: “We were a company with $500 million in cash, rail, port, wagons, the mine was already developed, the wash plant was going and they still managed to screw it.”

Steve Mallyon, managing director of Riversdale Resources, bought a 140 square-kilometre coal lease in southern Alberta in 2013 in order to do “what we did previously in places like Mozambique” he told Metal News in 2018. “We tend to try and build these places where no one else is building.”

After Rinehart purchased the Grassy Mountain project in 2019 from Riversdale Resources, the Sydney Morning Herald wrote, “Let’s hope our canny billionaire Rinehart isn’t being sold down the river by Riversdale 11.”

Rinehart at the time categorized the open-pit mining proposal on Grassy Mountain as an “outstanding project.”

That’s not how a joint panel environmental review led by the pro-industry Alberta Energy regulator viewed the company’s environmental assessment.

In a highly critical report, the panel concluded last June that Riversdale Resources (also known as Benga Mining) had overstated its economic benefits and underestimated environmental liabilities such as selenium pollution.

The panel also raised questions about coal quality. “Based on the evidence provided, it is unclear whether Benga will be able to produce a premium hard coking coal over the life of the project,” noted the review.

“The project’s significant adverse environmental effects on surface water quality and westslope cutthroat trout and habitat outweigh the low to moderate positive economic impacts of the project,” determined the joint panel review. “Therefore, we find that the project is not in the public interest.”

Last week, Canada’s federal environment minister accepted those recommendations and ruled “the project cannot proceed.”

Benga Mining, which regards the regulatory ruling as “anti-development,” has applied to Alberta’s Court of Appeal to strike down the regulator’s decision.

Its application contends that the regulator “erred in law by ignoring relevant evidence from Benga, or misconstruing that evidence, regarding surface water quality, the westslope cutthroat trout and habitat, and project economics.”

According to Australian corporate presentations and financial documents, Aussie coal speculators have been primarily drawn to the eastern slopes because of dwindling supplies of coking coal in Australia, low royalties offered by a friendly “natural resource” government, and a dramatic downturn in the oilsands which provides the speculators with what they call a “rare opportunity.” ![]()

Teaser photo credit: Abandoned Grassy Mountain Coal Mine near Crowsnest Pass, Alberta, Canada Keith McClary. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Grassy_Mountain_Coal_Mine_near_Crowsnest_Pass,_Alberta,_Canada.JPG