Today Breakthrough launches our new report Degrees of Risk, which looks at how financial regulators are underestimating systemic risks and may repeat the mistakes of the Global Financial Crisis. This extract examines the “net zero 2050” (NZ2050) scenarios produced by the central bankers’ Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) and finds they are not adequately addressing the real risks and uncertainties of climate change.

What does “Net zero 2050” (NZ2050) really mean? It is a critical question.

A number of institutions, including the IPCC, the International Energy Agency and the NGFS have produced NZ2050 scenarios, which will substantially influence national climate policy commitments made in the lead up to the climate summit in Glasgow in November 2021. Those scenarios and the models and assumptions underlying them will frame the outcome, as happened in 2015.

The Paris Agreement was lauded for its 1.5°C target, but had an underlying framework of target overshoot and a large role for currently non-viable technologies such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), backed by a good dose of scientific reticence about the state of the climate system and its tipping points.

The revised NGFS scenarios, published in June 2021, are being pitched as a standard for policymakers. The NGFS says the scenarios are “a foundation for analysis across many institutions, creating much needed consistency and comparability of results. A growing number of central banks, supervisors and private firms are already using NGFS scenarios… [It is] a suite of models, supported by a consortium of world leading climate scientists and modelling groups [and a] consistent set of pathways for global changes in policy, the energy system, and the climate.” In other words, NGFS is leading the way.

Australian financial regulators, including the Australian Prudential Regulatry Authority, draw on the NGFS scenarios, so their efficacy is materially relevant to the performance of those regulators.

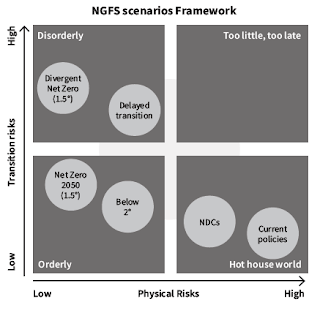

The NGFS provides six scenarios, four of which result in less than 2°C of warming by 2100, plus one at over 2°C and another at more than 3°C. The optimum scenario, called “Net zero 2050”, is clearly privileged in the NGFS presentations as the most desirable, and is given the most attention.

Like the Paris framing and the 2018 IPCC special report on 1.5°C, the NGFS scenarios rely on Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs). Such models reflect modellers’ view of society. Depending on how modellers perceive the roots of the problem to be solved, researchers says they will “design the model structure, including possible instruments and relationships within the model accordingly… Hence, the very structure of a model depends on the modeller’s beliefs about the functioning of society.” Consequently, IAM results have the capacity to privilege particular pathways and entice policymakers into thinking that the forecasts the models generate have some kind of scientific legitimacy. And this is the fundamental problem with the NGFS scenarios.

It is clear from NGFS presentation that the focus is on scenario choice, not risk management. Recognising that risks may be existential, especially in the higher scenarios, would bring a completely different approach to thinking about the risks, but this is entirely missing. And IAMs — like IPCC reports — focus on the probabilities, not the bad possibilities.

Some key issues of concern include the following.

Scenario choice: The NGFS identifies four scenario quadrants: “Orderly”, “Disorderly”, “Hothouse world”, and “Too little, too late”. Four under-2°C scenarios fit into the first two quadrants, and two are in “Hothouse world”. But there are no scenarios for the “Too little, too late” quadrant, even though it is important in scenario work to focus on the bad possibilities. As well, the two scenarios above 2°C appear poorly developed, whereas sensible risk management says they deserve special attention. The quantification of damages in the NGFS climate scenarios is grossly underdone. In the 3°+C scenario (“Current policies”)the effect on GDP at 2100 is −13%, which is extraordinarily low and stretches credibility. If there was a reasonable grasp of the consequences of more than 3°C of warming, then this scenario would be in the “Too little, too late” quadrant, because not only will the damage be very high, but so will the cost to business trying to transition to and survive in that world of catastrophe and chaos.

Underestimating damages. IAMs assume damages can be quantified, when in reality they are radically uncertain, and perhaps infinite, especially in the higher-warming scenarios. As noted earlier, some climate system tipping points have already been passed, and cascade effects are dangerously close. The NGFS scenarios chronically underestimate future damage, using IAMs that basically ignore non-linearities and cascades. The NGFS admits its damage estimates from physical risks “only cover a limited number of risk transmission channels. For example, they do not capture the risks from sea‑level rise or severe weather. They also assume socio-economic factors such as population, migration and conflict remain constant even at high levels of warming.” This, in itself, is enough to disqualify these scenarios from being seen as credible stories about alternative futures.

Technology choices and technocratic dreaming. Modellers make choices about the future mix of energy technologies. The recent IEA NZ2050 scenario, for example, has a doubling of nuclear power by 2050. Likewise, the NGFS scenarios allocate a sizeable role for fossil fuels in 30 years time. In 2050, in the NZ2050 scenario, gas production is still 50% of the 2020 level; fossil fuels are 32% of primary energy in the NZ2050 scenario and 50% in the “Below 2°C scenario”. To deal with this, a number of technologies either not proven or not deployed at scale are assumed, including direct air capture of CO2, and large-scale use of carbon capture and storage (CCS). Of the CO2 emissions savings to 2050, almost half come from technologies under development rather than those already in the market. Whilst the scenarios rely on a good deal on carbon dioxide removal (CDR), it is acknowledged by the NGFS that CDR is a big “if”, because such technologies “only currently take place on a limited scale and face their own challenges”.

Sustainability. The scenarios assume that the world economy will continue to grow for another 30 years as it has in recent decades, such that global production doubles between 2020 and 2050. Given that most resource use has not been significantly decoupled from production, this implies that the human world will become even more destructive of the planet and its finite resources. If at present humans consume 1.7 planet’s worth of resources each year, how much more irreparable damage will be done by 2050, and how many more of Earth’s planetary boundaries will be exceeded? No scenarios focus on lower-growth alternatives.

Fuels versus food. The purpose of CDR should be to reduce the level of atmospheric CO2 back to a safe level. But if you continue to use a lot of fossil fuels, then CDR has to be diverted into being an “offset” for continuing emissions, and hence demand grows for “natural offsets” such as forestation and the land and water required. Another demand on land is BECCS: biofuels supply 20% of primary energy by 2050 in the NZ2050 scenario. Carbon sequestration in the NZ2050 scenario is almost 8 billion tonnes of CO2 by 2050, including more than 3 billion tonnes from BECCS, even though current drawdown from BECCS is practically zero. BECCS uses crops grown for energy, and competes with land for food. This means that in the NZ2050 scenario, the amount of land available for crops decreases by 8% by 2050, even as GDP doubles and population grows by 20% in 30 years. Global demand for food would likely be around 50% higher than at present, with less cropland than now, which makes the land-use assumptions, in “Yes Minister” terms, “courageous”.

More broadly, there are the questions of the efficacy of scenarios and the role of climate–economy models. As discussed above, “Scenario planning does not forecast, predict or express preferences for the future; rather the story-telling paints internally-consistent pictures of alternative worlds which might emerge given certain assumptions, that are credible in the light of both known and lesser known factors.” But some NGFS scenario assumptions are either not credible or ignore significant factors.

The NGFS puts its model-based scenarios at the centre of the task that central banks and regulators face with climate-driven financial disruption. It claims that these “detailed scenarios” are a “milestone” in overcoming “a major obstacle” and a “foundation for analysis” of the risks. But the reality is that they are not adequately addressing the real risks and uncertainties of climate change.

BIS’s The green swan report concludes that scenario-based analysis “is only a partial solution to apprehend the risks posed by climate change for financial stability”, in part because the models being used “may not be able to accurately predict the economic and financial impact of climate change because of the complexity of the links and the intrinsic non-linearity of the related phenomena”.

Moreover, the scenarios presented by NGFS do not take into account and describe the full range of alternatives. The four key scenarios are based on one set of assumptions: Paris compliant, continued and unsustainable economic growth, a reliance on technologies not yet proven or deployed at scale, overshoot of the temperature target, a big role for gas for many decades to come, and denial of key dynamics of the climate system. No time frame shorter than 2050 is explored, nor any scenarios with active cooling in the shorter term to restore vulnerable ecosystems. This suggests the NGFS exercise has been largely about mapping a predetermined path.

In a word, the scenarios privilege advocacy of one particular path over a dispassionate articulation of multiple, wide-ranging perspectives and possible, alternative futures. Indeed, it is arguable, given the evidence of climate impacts given in this report, that most of the NGFS scenarios should reside in the “Too little, too late” quadrant.