Last week, part two of England’s National Food Strategy (NFS) was published, providing a broad overview of the state of the “food system” – an all-encompassing term that covers the production, processing, transport and consumption of food – in England.

The NFS is the culmination of more than two years’ worth of meetings and dialogues with industry leaders, academics, policymakers and the public.

The first part of the strategy, published in July 2020, provided recommendations for the government to address food insecurity and hunger in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic. The newly published second part has the stated goal of providing a “comprehensive plan for transforming the food system”.

The report, which is more than 150 pages long, lays out 14 recommendations for the UK government to consider, including financial incentives, reporting and trade standards and targets for long-term change in the food system.

The government has committed to producing a white paper and proposals for future laws in response within the next six months, although the early response from UK prime minister Boris Johnson has been “noncommittal” to many of the NFS proposals, according to the Guardian.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief examines the report and explains how its recommendations align – or do not align – with the UK’s climate targets and decarbonisation goals.

- What is the National Food Strategy?

- Why is the food strategy important for tackling climate change?

- What parts of the food strategy could make the biggest impact on climate change?

- What are the limitations of the food strategy in addressing climate change?

- How does the food strategy address competing land needs?

What is the National Food Strategy?

The NFS was commissioned by the UK government in 2019 as the first independent review of the government’s food policy in nearly three-quarters of a century.

Its aim was to provide a roadmap for transforming the food system from its current state to one that is healthier for the population and the planet.

Although the scope of the report covers England alone, it notes that the home nations’ “food systems are so tightly interwoven as to be in places inextricable”. It continues that it hopes the devolved governments “might in turn find some useful ideas” in the strategy.

The report itself calls the food system “both a miracle and a disaster”. While the current food system is capable of feeding the “biggest global population in human history”, it says, this comes at a high environmental cost. The report notes:

“The global food system is the single biggest contributor to biodiversity loss, deforestation, drought, freshwater pollution and the collapse of aquatic wildlife. It is the second-biggest contributor to climate change, after the energy industry.”

The reaction to last week’s release saw members of parliament, celebrity chefs and even rockstars weighing in on its significance.

Some have criticised the recommendation to tax wholesale sugar and salt as unfair or as disproportionately affecting lower-income families. Others say that the measures laid out in the report do not go far enough towards making the food system more sustainable.

This report by @food_strategy has some interesting and far reaching ideas that would mean a big change for the better in our food system and make us all healthier. I hope that these plans will be taken up by this government. https://t.co/gl5rZJCrhO

— Mick Jagger (@MickJagger) July 15, 2021

However, the NFS has certainly brought these issues to the forefront, Edward Davey, the international engagement director of the Food and Land Use Coalition, tells Carbon Brief. He explains:

“[The report] brings everyone around the table for a dialogue about what kind of system do we have, what kind of system do we wish to bring, what are the trade-offs and could governments do things differently.”

Davey adds that, in his view, “every country in the world would benefit from doing something of this kind”.

Why is the food strategy important for tackling climate change?

Research suggests that the food system is responsible for about one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions. And the numbers are about the same for the UK, Dr Marco Springmann, a population health researcher at the Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Food, tells Carbon Brief. (The NFS report puts that figure at 19%, but different studies draw different boundaries around what counts as the food sector.)

Under its commitments to the Paris Agreement, the UK has pledged to reduce emissions from 1990 levels by 68% by 2030. The government has also set a legally binding target to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Springmann says:

“Without addressing the emissions of the food system, it will not be possible to meet those climate change obligations [laid out by law] and to contribute to mitigating climate change.”

Nearly half of all food-related emissions are due to agriculture, including rearing livestock.

The methane produced by cows and other ruminants is “estimated to have caused a third of total global warming since the industrial revolution”, the report notes.

Other major contributors to the emissions include transportation, food and fertiliser manufacturing and packaging.

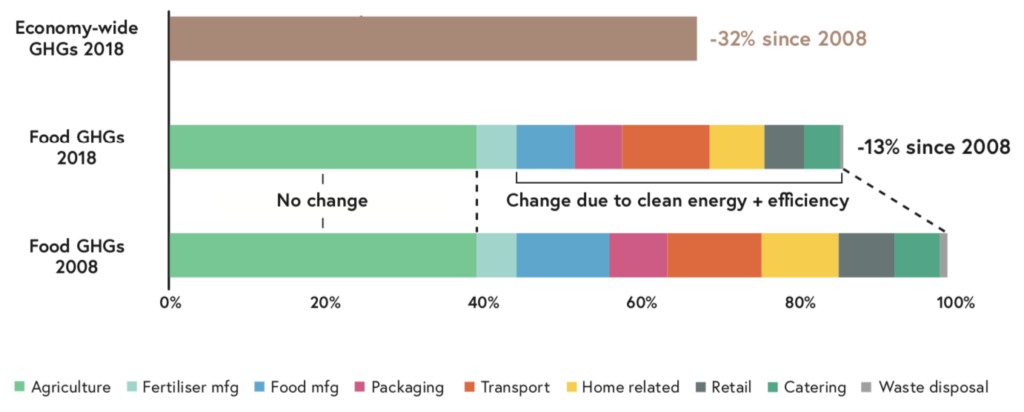

The food system has seen significantly smaller reductions in sector-wide emissions since 2008 as compared to the economy as a whole: economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions have decreased by nearly one-third since 2008, but food-related emissions have decreased by only 13% over the same time.

Furthermore, virtually all of the gains made in the food sector have been due to cleaner energy and increased efficiency in the energy sector. Changes due to agriculture have been negligible – as seen by the large green bar in the chart below.

Greenhouse gas emissions from the food sector as a percentage of the 2008 emissions in that sector. By 2018, emissions had reduced by 13%, but none of this change was due to improvements in agriculture. Overall emissions decreased by 32% over that same time period. Source: The National Food Strategy, Part II.

Trying to create a healthier population while farming in a less damaging way requires collaboration across disciplines, Davey tells Carbon Brief. He says:

“There’s quite a lot of siloed thinking about the food system. So, from the point of view of integrated national policymaking that delivers, it’s fantastic.”

What parts of the food strategy could make the biggest impact on climate change?

Many of the recommendations made in the report relate in some way to climate change or environmental sustainability. These recommendations include:

- Guaranteeing funding for agricultural payments until at least 2029 at the current level of £2.4bn in order to aid in the transition to sustainable farming. The report also stipulates that at least £500m of this should be “ring-fenced” for schemes that encourage habitat restoration and carbon sequestration, such as peatland restoration.

- Creating a “rural land use framework” that will advise on the best way that any given piece of land should be used – whether for nature, agriculture, bioenergy or something else. The proposed framework uses the “three compartment model”, which strives for a balance between semi-natural land, low-yield farmland and high-yield farmland to meet the targets of both sustainability and food production.

- Investing £1bn in UK Research and Innovation and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), as well as smaller centres to spur innovation to “create a better food system”. The funds would be aimed at innovating fruit and vegetable production, methane suppressants and alternative proteins, among other areas.

- Reducing meat consumption by 30% over the next decade. The report stops short of recommending a tax on meat to achieve this aim (as it recommends for sugar and salt bought wholesale). Instead, it states, the government should aim for “nudging consumers into changing their habits”.

- Introducing mandatory reporting on a variety of metrics for food companies employing more than 250 people. These metrics would include the tonnage of food waste generated.

- Creating a national food system data programme, which would allow businesses and the government to evaluate their progress on the goals laid out in the report. The programme would include both the land-use data and the mandatory reporting data described above. Bringing these two types of data together, the report writes, will help “create a clear, accessible and evolving picture of the impact our diet has on nature, climate and public health”.

Davey calls the recommendations a “good starting point”. However, he adds:

“The question is how quickly will those reforms really address the climate challenge…I think the jury’s out. Is it not as ambitious as it should be, from the point of view of what the land sector needs to do to achieve the UK national targets? I don’t know. It’s certainly a step in the right direction, but there’s probably an argument that it’s not ambitious enough.”

What are the limitations of the food strategy in addressing climate change?

The recommendations “seem to be almost sort of looking backwards rather than looking forward”, Prof Maggie Gill of the University of Aberdeen, tells Carbon Brief. She adds:

“Another thing that seems to be missing is that foresighting, where’s the world going to from other sectors…There’s going to be a transformation in farming…And it’s going to take years [for the recommendations in the report] to come to fruition by which time the world may have changed.”

Gill also notes that the report, while thorough, does not fully consider the unintended consequences of its recommendations. For example, a much higher proportion of fresh fruits and vegetables is wasted than meat. So the recommendations to eat less meat may increase the amount of food waste.

The food system “is very complex”, Gill says, “but I don’t think that’s any excuse for not actually highlighting some of those concerns right at the start”.

The commissioning of the report – it was led by businessman and restaurateur Henry Dimbleby – means the report itself “shows a little bit of a skewed focus” towards business-focused solutions, Springmann says.

For example, the recommendation towards investing in innovation lists alternative proteins as a key area in need of research funding. However, Springmann says, the alternative-protein industry is already very well-developed. He tells Carbon Brief:

“There are already plenty of meat substitutes on the market and even more so when you consider natural meat substitutes like more beans, lentils and those kinds of things…Explaining more clearly that healthy and sustainable diet doesn’t necessarily need to include processed meat alternatives would have been important, but that was missed there and instead this sort of pro-business angle was taken.”

The report also “really shied” away from taking a strong position on reducing meat consumption, Springmann says, with impacts on both the environment and public health. He says:

“If you take the food system as a holistic thing, then you really need to address all kinds of issues. And if you want to address properly the environmental concerns, plus the health concerns, you really have to address the overconsumption of animal-sourced foods in our diets.”

How does the food strategy address the competing interests of agricultural land use and land use for carbon sequestration?

Nature-based solutions, such as peatland restoration and afforestation, are expected to play a major role in many countries’ and companies’ net-zero targets, but many of these require the repurposing of agricultural land.

As a result, the report says, the food system is being “asked to perform a feat of acrobatics” in providing enough land to produce the necessary food, but also to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions.

In order to address these competing interests, the report calls for a national land-use strategy to best allocate land to nature, carbon sequestration and agriculture.

Developing the strategy will involve collecting data on agricultural productivity, priority nature areas for preservation (such as existing peatlands) and highly polluted areas. It will also build on work such as England’s trees and peat action plans – released earlier this year – in order to identify the land best suited for nature restoration.

The report notes that with the right incentives for farmers to repurpose their land, the strategy could be mutually beneficial towards farmers and the environment. It states:

“The kind of land that could deliver the greatest environmental benefits is often not very agriculturally productive. The most productive 33% of English land produces around 60% of the total output of the land, while the bottom 33% only produces 15%.”

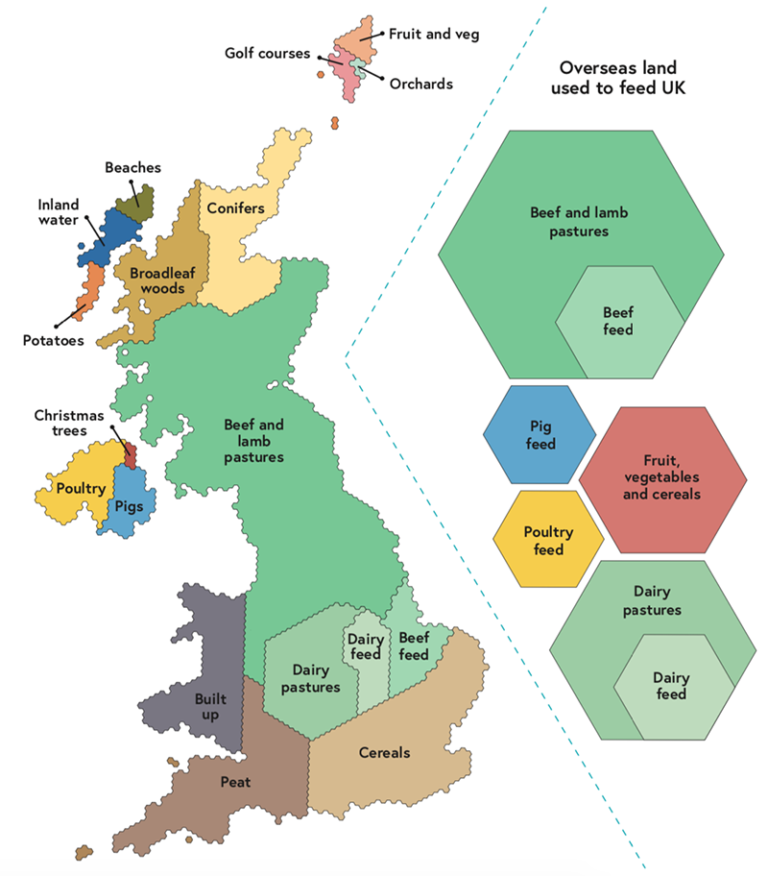

Reducing meat consumption would also help alleviate the strain on land resources, the report finds. About 70% of the landmass of the UK is devoted to agriculture, with feed and pastures for beef and lamb taking up the vast majority of that land.

The chart below shows how all land in the UK is allocated (left) and how much overseas land is used to produce food for the UK (right).

UK land area divided up by purpose. About 70% is devoted to agriculture, mainly livestock and livestock feed and pasture. The right-hand side of the chart, using the same scale, shows how much land is used overseas to produce food for the UK. About half of the total land use takes place overseas. The combined land area for rearing beef and lamb for UK consumption is larger than the UK itself. Source: The National Food Strategy, Part II.

The UK’s Climate Change Committee (CCC) has estimated that just over 20% of agricultural land must be rewilded or converted to bioenergy or other, non-agricultural crops in order to achieve net-zero by 2050. The NFS report states:

“Globally, the biggest potential carbon benefit of eating less meat would not actually be the reduction in emissions, but the opportunity to repurpose land so that it sequesters carbon.”

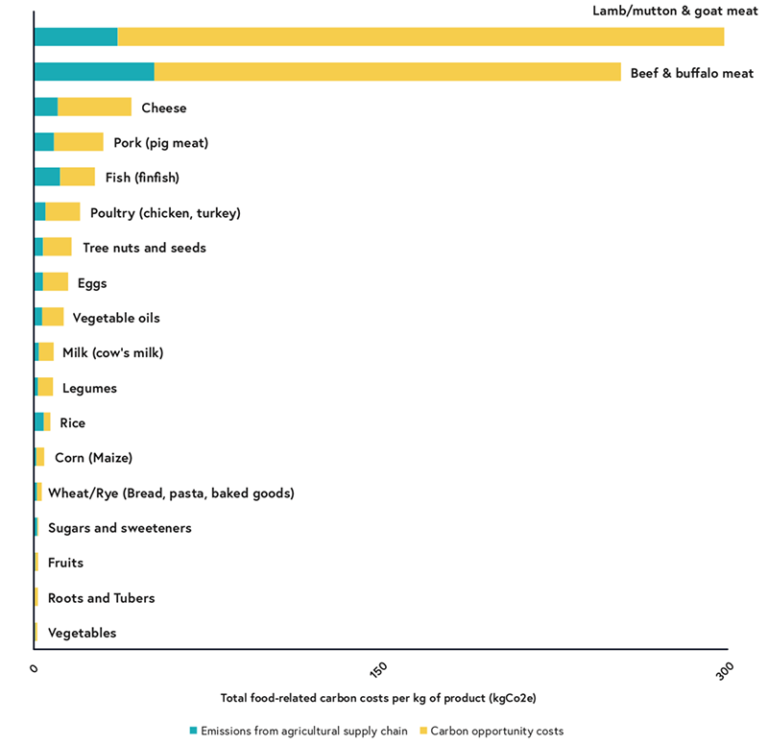

The chart below shows that when the carbon sequestration “opportunity cost” (yellow bars) is added to the emissions of various food groups (teal bars), the carbon cost of lamb and goat meat actually surpasses that of beef, due to the large amounts of land needed to graze those animals and their appetite for tree saplings.

Total carbon costs (kgCO2e) per kilogram of various food products. The teal bars indicate the direct emissions associated with the supply chain of each product, while the yellow bars show the carbon “opportunity cost”, meaning the amount of CO2 that could be sequestered in the land used to produce that food. Source: The National Food Strategy, Part II.

The government has committed to producing a response to the strategy, including proposals for new legislation, within the next six months.

However, UK prime minister Boris Johnson has already indicated his hesitancy to support some of the policy recommendations laid out in the report. This does not bode well for the report’s adoption, warns Springmann:

“Implementation of any of those recommendations really requires political will…The recommendations themselves could have been more progressive, but even the ones that are there don’t seem to resonate very much with policymakers that are in power at the moment.”

Teaser photo credit: Longhorn cattle at Knepp Wildland 2019. By PeterEastern – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=98133375