Ed. note: This article first appeared on ARC2020.eu. ARC2020 is a platform for agri-food and rural actors working towards better food, farming, and rural policies for Europe.

What does a socio-ecological transition mean for farmers? Farmers from the Nos Campagnes En Résilience project share their thoughts on social issues in farming, the role of farms in the community, and how Nos Campagnes En Résilience can help to build rural resilience in France.

In France, collective farms are quite common (known as a Groupement Agricole d’Exploitation en Commun, or GAEC). Social issues on the farm are central to farming in a collective set-up. But these farmers are also keen to look beyond the farm to build community and connection.

Cédric Briand is part of a collective dairy farm in Brittany with two other partners (pictured above). They manage a a herd of Bretonne Pie Noir, a local heritage breed of dairy cow. All of their milk is processed on-farm, where they produce artisan cheeses.

Ludovic Boulerie is an artisan baker and farmer in a collective farm in Nouvelle-Aquitaine in the West of France. Together with his two farming partners (pictured below) they produce cereals and aromatic herbs and bake bread in the on-farm bakery.

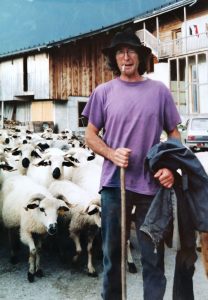

Gilles and Marie Avocat are retired sheep farmers and cheesemakers who were part of a collective farm in the French Alps. They have always been very involved in the community as advocates for local organic food.

Farming can build community through food

Ludovic puts it succinctly: The end goal of farming is to feed the population. So there’s a direct link between farmers and their local communities. Farming can build community through food.

Cédric sees a similar link: Short supply chains connect the local community with their farm. Farming should be anchored in the local area to build community. Re-localising the economy is part of that. A short supply chain is not just direct sales – it could be re-localising tools for production or processing, for example a micro dairy.

In a business, there’s a boss who makes decisions; in a collective set-up, that’s never the case, says Cédric. In a collective, you have to be organised! To make sure everyone gets time off, for example. The GAEC (collective farm – Groupement Agricole d’Exploitation en Commun) has not managed to replace the traditional family system. On his farm they spend a lot of time and money reviewing how they do things: it’s an ongoing process.

Agri-culture

To truly be part of the conversation, farmers also need to engage with their communities in other ways, beyond farming. In culture in the broadest sense.

That’s why Cédric wants to make his farm into a truly farm-to-fork venue, where you can eat what was produced on the farm. It’s symbolic. Also it gets the balance right between economic, social and environmental sustainability – and community.

Ludovic points to some concrete examples of culture in agriculture. He mentions the Brigade Rurale d’Intervention Culturelle (BRIC), a local group that puts on concerts and plays in farms, making culture more accessible for rural communities.

Another group, Le Plat de Résistance, prepares meals from local ingredients to feed protesters, such as a group of performers occupying a theatre. The group also runs healthy eating programmes for disadvantaged communities.

Social justice

Solidarity

Solidarity is an important aspect for retired farmer Gilles, who remembers the lively debate among farmers in the 1980s around importing soya from Latin America. Farmers wanted to escape the spiral of consumption, but they worried about the repercussions: if we stop buying the soya, will we be putting those producers out of work? How can we cooperate so that everyone does OK? That debate is even more contentious today.

Access to land

Gilles has always been very socially engaged, and so he is keenly aware of the access to land. As he puts it, land draws the map of connections. You can build a shed in a small space, you can put together a herd in a small space, you can concentrate your equipment, but land draws the map of connections between the farmers.

Knowledge transfer

Having trainees is hugely important for small farmers: as a way to pass on knowledge, and for social contact. You have to think about passing on your farm: how the young farmer will take it on, what everyone’s role will be, when it’s the right time to retire.

ARC2020 can help to build bridges

Cédric also wants to ask questions. As farming becomes increasingly specialized, what does it mean to be a farmer in the 21st century? Is it simply producing meat or milk, or is it more than that?

He sees ARC2020’s role as facilitating dialogue between farmers and citizens. ARC can help to build bridges between the local and European level, and help Europe’s farmers and rural actors to gain fresh perspectives beyond local level. Get out of our bubbles, but don’t create new ones at European level.

Farming is changing

Farming is changing. Nos Campagnes En Résilience is an opportunity to take a step back and ask questions, but also to pull together. There are so many well-intentioned organisations out there: we need to get the message across that it’s in our interest to work together and find common cause. As Cédric points out, we all talk about this but we aren’t doing it.

Gilles echoes this sentiment. We need to become more effective to increase our impact at European level. ARC2020 could bolster existing organizations at French and European level.

The way we’re doing it is viable

Ludovic points to a growing network in France – and beyond – is trying to lift small farmers out of conventional farming, which is often based on habits that aren’t even that old.

New entrants who often bring with them new practices or at the very least, new experiments at a more human scale.

Ideally, all of these experiments on the ground in France, once they are ecologically and financially viable, should serve to influence lawmakers in deciding the future of European agriculture.

Subsidies at the moment are not suited to the agroecological farming we want to work towards. Farmers need to be given the means to live off their work with dignity. People need to understand the importance of the quality and origin of their food, stresses Ludovic.

Cédric suggests that the CAP should incorporate cultural, social and environmental aspects, and workers.

Ludovic leaves us with some final words: I think farming, the way we’re doing it, is viable and gives people access to healthy food. ARC2020 can show us that we’re right and that change is possible.

This is a summary of conversations translated from French by ARC2020. Read the full conversations in French with Cédric , Ludovic and Marie and Gilles (French only).

Nos Campagnes En Résilience is ARC2020’s project to help build rural resilience in France. Visit the project page here and follow us on Instagram, LinkedIn and Facebook. If you’d like to get involved, contact our project coordinator Valérie Geslin.

Teaser photo credit: Cédric, Mathieu and Hervé of the collective farm (GAEC) La Ferme des 7 Chemins in Brittany. Image courtesy of La Ferme des 7 Chemins via Facebook