Oh, the bright shining lies.

When it comes to energy and climate change the political rhetoric promises four great and positive happenings.

New oil and gas infrastructure will fund Canada’s energy transition.

Emissions will be conquered by technologies that bury carbon in the ground at great cost or don’t yet exist.

Canada will meet all of its climate change goals and ramp up oil and gas production at the same time.

The energy transition will be effortless and orderly because there is lots of low hanging fruit to pick.

These national assumptions, repeated daily by politicians and the media like some weird liturgy, give David Hughes, Canada’s foremost energy analyst, a headache.

The earth scientist and former researcher for National Resources Canada has been crunching inconvenient energy numbers for decades with a frightful reliability. His new report, Canada’s Energy Sector, published by the Corporate Mapping Project and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives this week, shatters many illusions.

As a committed oil-exporting nation, Canada still hasn’t grasped some important physical realities, says Hughes.

Rising emissions mean the target is receding

Let’s start with some emission truths. Canada has never met a single target for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. It stands out internationally as a laggard. At the end of 2019 it had reduced its GHG by just 1.2 per cent from 2005 levels.

Two G7 nations have jacked up emissions since the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2016: Canada is the worst at 3.3 per cent followed by the United States at 0.6 per cent.

In contrast, Italy reduced emissions by 4.4 per cent and Germany by 10.8 per cent.

In its annual energy report JP Morgan, no environmental champion, noted,

“To keep global emissions flat, the developed world would need to reduce emissions by ~4 per cent per year, which is five to six times faster than the current pace.”

Canada, a petro state, is not doing that. Instead emissions keep growing in almost every major sector including buildings, transportation and oil and gas production.

Oil and gas production and exports now account for 26 per cent of emissions. That’s more than any other industrial sector except for transportation.

To date, only one economic sector in Canada has actually cut emissions significantly between 2005 and 2019 and that’s the electricity sector, and all mainly due to the phasing out of coal.

The Canadian Energy Regulator (formerly the National Energy Board) came out with two emission scenarios last year, reports Hughes.

One of CER’s projections assumed the Canada would do nothing further about climate change while the other assumed we would eventually do something through additional policies. For the record the CER has never assumed that Canada might actually reduce emissions.

In the do-something or “evolving scenario,” the CER assumes oil and gas production won’t peak until 2039. By 2050, in this scenario, Hughes found that the country would still be 32 per cent above an 80 per cent reduction target even if every economic sector other than oil and gas production is reduced to zero. “It is a complete disaster,” said Hughes.

In the do-nothing scenario, well, emissions would be 94 per cent above targets by 2050.

Fossil fuel revenues are dropping

Meanwhile, the Trudeau government contends that revenue from oil and gas exports will fund the glorious energy transition to renewables.

This optimistic claim partly explains why the government has invested more than $12 billion in the Trans Mountain export pipeline and is subsidizing the LNG Canada export project.

Unfortunately, the facts don’t support this Liberal assumption of big earnings, reports Hughes.

For starters, royalty revenue from oil and gas isn’t going up, but down. Even though oil and gas production has increased by 47 per cent in the last two decades, the amount of dollars pouring into government coffers from royalties has dropped by 45 per cent since 2000.

This fast downward trend explains why petro states such as Alberta and Newfoundland are wailing and having trouble paying their bills.

Alberta has an emergency on its hands: non-renewable resource revenue per barrel of oil or its equivalent in liquids or methane has dropped by 72 per cent in the last two decades. Yet the province wants to export more fossil fuels for diminishing returns.

Tax revenue from oil and gas is also falling like a stone. In 2009, tax revenues from the energy sector including the oilsands once totalled 14 per cent of all corporate taxes in Canada, reports Hughes. But in 2018, the energy sector contribution dropped to less than four per cent.

Since 1997, the energy sector’s contribution to GDP in Canada fell from 11 per cent to nine per cent in 2019.

Meanwhile, the capital-intensive industry has been diligently automating and laying off people. It only employs about one per cent of the population (five per cent in Alberta). Direct employment in fossil fuel extraction has fallen 23 per cent since peaking in 2014.

So even as oil and gas production reaches record levels in the country, revenue from Canada’s oil and gas sector has dropped to record lows.

In sum, the oil and gas industry, which can’t even fund cleaning up its orphan and abandoned wells, will not fund any energy transition.

“The revenue will not only not fund a transition but makes a transition impossible because of the emissions associated with it,” Hughes told the Tyee.

‘Capturing’ carbon is a techno-mirage

Given that emissions are rising and revenues are plummeting, the Trudeau government promises to bury carbon in the ground, relying on carbon capture and storage to dispatch rising emissions. Or they hope to suck it out of the air with novel technologies that burn lots of energy and dollars.

The government even promises that carbon capture and storage will “turbocharge” the oil and gas industry.

Carbon capture and storage exists in limited form as a costly and energy-intensive technology. To date, industry has largely injected carbon into the ground to push out more hydrocarbons. As a result, one group of researchers found that efforts at burying carbon in the ground “are net CO2 additive: CO2 emissions exceed removals.”

The technology also does not scale up. To bury just 15 per cent of global emissions, estimates the JP Morgan report, the world would have to build CCS infrastructure (compression, piping and injection facilities) greater than that used by the world for oil extraction and consumption. Achieving that goal by 2050 seems unlikely.

Not only is CCS a dead energy loss but it is a techno-fix “that will never scale up to the levels needed,” says Hughes.

There is no low hanging fruit

As things now stand, the oil and gas sector produces more than 26 per cent of the nation’s emissions.

That’s more than any other economic sector like agriculture or heavy industry. Only transportation outdoes oil and gas in emissions for obvious reasons.

Given that Canada has closed most of its coal-fired plants, Hughes asks where the reductions will come from.

Meanwhile, the CER forecasts that net oil exports will grow 42 per cent and net gas exports will grow 186 per cent over the 2019 to 2050 period.

In his report, Hughes asks an inconvenient question:

“If oil and gas production increases will not result in strong growth in jobs and government revenues and will result in Canada missing its emissions-reduction targets, why would the country allow these increases to happen?”

He offers a difficult solution.

“Production has to come down. There is no other way.”

The energy analyst argues that Canada won’t meet its emission targets unless it dramatically lowers export production, cancels the Trans Mountain pipeline and ends LNG subsidies.

“The path ahead to achieve Canada’s emissions-reduction targets will be difficult, and reducing emissions from the oil and gas sector will be a critical part of the solution.”

Nor does Hughes imagine a green panacea on the horizon.

Given the nation’s cold climate and great distances, he thinks the nation will need fossil fuels beyond 2050. He doesn’t think we should be exporting what’s left abroad and for diminishing returns.

As things now stand, Canadians power their lives largely with fossil fuels. It accounted for 96 per cent of the energy use by the transportation sector, 78 per cent by the industrial sector, 67 per cent by the commercial sector and 52 per cent by the residential sector.

To make any kind of significant stab at emissions, that share of energy consumption needs to drop to around 30 per cent by 2050. (CER’s do-something scenario will only bring fossil fuel consumption down to 62 per cent by 2050.)

Canadians rank among the highest per capita energy consumers in the world, at five times the world average and 32 per cent higher than Americans.

But as energy ecologist Vaclav Smil has argued, we lived comfortably in the 1950s and 1960s when energy consumption was much less. And that’s where we need to go.

Techno solutions likely won’t get Canada there but radical reductions in energy consumption across all sectors (and among the rich) might, says Hughes.

Nor will any of this be pain free. Only difficult decisions lie ahead.

Verisk Maplecroft, a risk analysis group with an office in Calgary, looked at the global data for G20 countries which includes high emission Canada, and concluded, like Hughes, that an orderly energy transition is highly unlikely.

“Our data underscores that it is clear there is no longer any realistic chance of an orderly transition. Companies and investors across all asset classes must prepare for at best a disorderly transition and at worst a whiplash from a succession of rapid shifts in policy across a host of vulnerable sectors,” said a recent report.

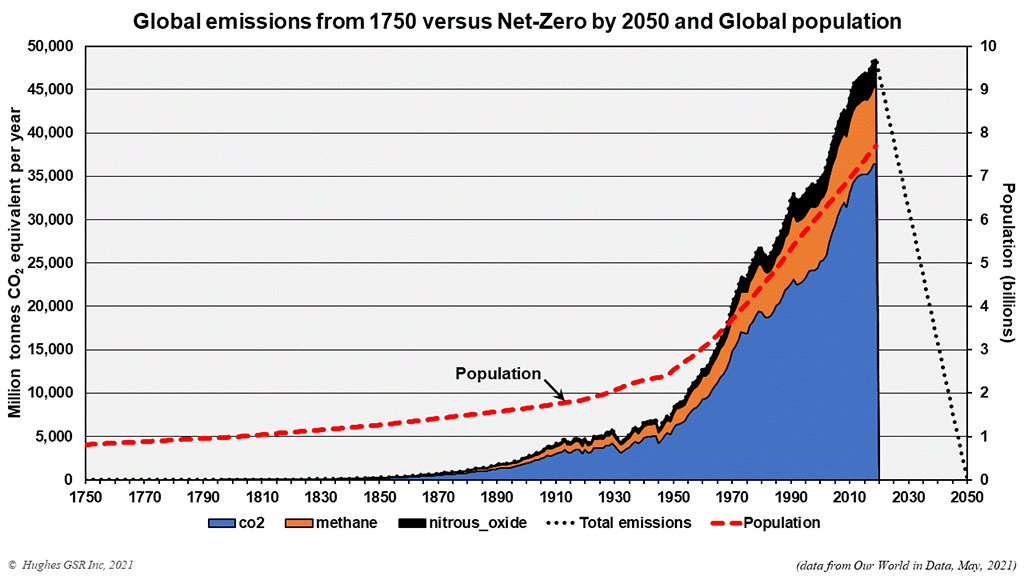

To appreciate the daunting nature of the energy challenge, just take a glance at the illustration below that Hughes provided The Tyee.

It shows the trajectory of population, total anthropogenic emissions and GHG emissions over time. The graph looks like a steep and unrelenting ascent up a mountain over 150 years.

It shows the trajectory of population, total anthropogenic emissions and GHG emissions over time. The graph looks like a steep and unrelenting ascent up a mountain over 150 years.

The assumptions offered by the Canadian government propose an almost fanciful and imaginary descent by 2050. No seasoned climber or skier would relish such a steep descent.

The realities bear repeating. Emissions are rising and targets will not be met.

Yet Canada thinks it can beat climate change by exporting more fossil fuels at the same time. The government promises easy solutions and more techno fixes, telling us we should not worry and be happy.

“It is probably political suicide to tell people that they are going to have to consume less energy and lower their lifestyles,” said Hughes. “And that explains why politicians promise the moon.”

Oh, the bright shining lies. ![]()

Teaser photo credit: By TastyCakes is the photographer, Jamitzky subsequently equalized the colour. – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2004921