In 1989, a few months before the Berlin Wall would collapse, I was co-leading an international student group in a program called Peace Studies Around the World that took us to East and West Berlin. In discussions with some of the leaders of the civil rights and opposition movements in East Berlin, I witnessed with my own eyes how even the very people who were on the frontlines of forces that eventually would bring down the Berlin Wall — effectively ending the cold war system — had no idea what a far-reaching impact their actions were about to have. In my life, I have seen tectonic shifts several times. What I have learned from those moments is that, before they happen, almost no one actually believes that such profound changes and shifts will occur. But once they happen, many people are quick to explain why they did.

Image by Kelvy Bird

Today it feels as if we are in a somewhat comparable moment. Across many places and networks it feels as if we are on the verge of yet another far-reaching movement. A movement that isn’t just about changing social structures but is also about shifting human consciousness — the capacity to operate from a deep sense of purpose that transcends institutions, borders, and boundaries. A movement that is calling on us to cultivate the inner conditions that allow for transformational change. A movement that allows us to radically reconnect with each other, with our planet, and with our evolving human consciousness in order to heal the three big divides of our time: the ecological, the social, and the spiritual.

This movement was foreshadowed by powerful precursors such as the youth-led Fridays For Future protests in 2019 (when over 14M people took to the streets), the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 (when 26M people took to the streets in the US alone, making it the biggest civil movement in the history of this continent), as well as the massive civil protests that swept across large parts of Latin America, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East over the past few years.

Most people, if you talk to them today, have a felt sense that our current societal model is broken and that more disruptive changes are coming our way. Most of these people would also say that, personally, they’d prefer to be part of a different story, building a different future. But many would be quick to add that they don’t know how to make that happen. Considering the gap between the modest actual and the massive possible change, we need to ask ourselves: Is this the moment when we should articulate the future we want to create with much more radical clarity?

After more than half a century of building awareness around our social and planetary emergencies — initially sparked by the civil rights movement of the ’60s, the environmental and women’s movements of the ’70s, the Indigenous and decolonization movements over many decades and centuries — it feels as if we’ve finally reached the moment when we have to stop kicking the can further down the road. If this is the decade when all the “streams” finally converge into a larger “river” of global movement building — if this is the decade of transformation — what can we learn from the Covid disruption about how to move forward?

Here are ten lessons that may help us to make sense of what is emerging from our experience.

(1) Denial is not a strategy.

On the list of countries with the highest Covid death toll, the United States, Brazil, India, Mexico, and the United Kingdom are at the top. That list, needless to say, reads almost like a who’s who of populist (and in part authoritarian) leadership in 2020: Trump, Bolsonaro, Modi, Lopez Obrador, and Johnson — leaders who downplayed the pandemic and delayed or undermined a timely public health response in their countries. Leaders who routinely put their (or their party’s) approval ratings ahead of the health of their people, for example, by holding massive political events without social distancing (despite the spike in Covid cases).

These behaviors of denial (not seeing the amplified risk you are inflicting on your country) and of de-sensing (not empathizing with those who are most at risk) may have worked for the respective leaders for a little while; but today, in 2021, everyone knows that denial is not a workable strategy.

(2) We are witnessing a collapse of walls that — unlike in 1989 — are not between two systems but between system and self.

The current collapse of walls between self and system has been unfolding over three major stages and disruptions. The first was during the early stage of Covid-19 last year. Covid taught us everything about our level of interdependence — both societal and ecological. When something happens in Wuhan, China, it can affect people anywhere else in the world within weeks or months. When something happens in Manaus, Brazil, it can affect most of Latin America shortly thereafter. If you think that hoarding vaccines will make you safer in, say, the US (“America First” thinking), then you probably have not thought this through in the context of our real interconnectedness.

The second wall collapsed when, after the murder of George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter movement became a global phenomenon. In this case the collapse did not happen on the level of the mind (becoming aware of our interdependence) but on the level of the heart. Suddenly I could feel the pain that others felt — a pain that was inflicted on and felt before by others, but that had not penetrated the boundaries of my heart. Watching the nine and a half minutes of the killing of George Floyd changed that for good.

The third stage and collapse of walls began with the attack on the US Capitol on January 6. This time, the disruption focused on the foundations of who we are as a society and who we want to be. When you see the world’s mightiest military superpower — with a defense budget bigger than that of the next ten countries combined — demonstrating utter helplessness against a few hundred insurgents, then you know that the system has been hit in its blind spot. The blind spot in this case is inside this country’s borders: White-supremacy-based domestic terrorism, ignited by the then occupant of the Oval Office. That, in a nutshell, is the third wall that is in the process of collapsing now: one that shifts our attention from an overfocus on the issues outside our own boundaries to include the issues that originate from within.

(3) In the age of the Anthropocene, societal structures are fluid, not frozen.

As the 2020 UN Human Development Report has clarified in great detail, in the age of the Anthropocene — that is, in the age of humans — the primary source of problems is us and our often outdated patterns of action and thought. The report also points out that the primary source of finding solutions lies in our capacity to reimagine and reshape these patterns. Which is where the next learning experience from Covid comes in: One of the most important lessons of the past year-plus concerns how profoundly we as human beings can reshape our own ways of operating. Societal structures are fluid, not frozen. Among all of the species on earth, only human beings can consciously connect with and reshape their future. We have a choice whether to perpetuate the old rules of our collective behavior — or to change them.

We did that when we started to bend the Covid curve. We did that when we started to respond to Covid in ways that went beyond the neoliberal orthodoxies that have shaped the economic behavior of the OECD countries over the past 40 years. Suddenly we are able to find a trillion dollars here, another 2 or 3 trillion dollars there. Suddenly we see the flow of massive public investment in people, in infrastructures to combat climate change. Suddenly we see a commitment to net zero emissions by 2050 from countries responsible for about 70% of the world’s GDP. This is the beginning of a significant shift that even just a year ago most people would have considered impossible.

All this points us to an often-ignored distinction between the natural sciences and social sciences. Wherever you are on the planet, if you drop an apple you can be sure that it will fall to the ground. The law of gravity applies everywhere on earth. However, the same is not true in the social sciences. Metaphorically speaking, when I let go of an apple, I don’t know for sure whether it will drop downward or float upward. This is because the invariances or “laws” that govern social behavior only apply under certain conditions (we call these “third variables”). The most important of all third variables is human consciousness. The moment you change the awareness of people in a system, then the rules that govern their behavior can begin to change too. That’s why I like to summarize Theory U like this: “I pay attention this way; therefore it emerges that way.” The quality of my listening co-shapes how a conversation unfolds. The way I pay attention co-shapes how reality unfolds.

If we apply this principle of social plasticity to the level of the collective, to the system as a whole, we see that social structures are fluid, not frozen; they evolve, just as our human consciousness does.

(4) The real superpower of the 21st century is our capacity to realign attention and intention on the level of the whole system.

The true superpower of the 21st century is not the United States or China. Rather, the true superpower of this century started to show itself in moments when we were bending the curve in fighting the pandemic. It showed itself when the Black Lives Matter and the climate justice movements suddenly became global phenomena. It shows up wherever human beings begin to shift their behavior by realigning attention and intention through awareness-based collective action.

Attention matters because energy follows attention. Wherever you put your attention, that’s where the energy goes. At the moment when we bend the beam of collective attention back onto our own process and when we begin to see ourselves through the eyes of others, and the eyes of the whole, then we begin to unfreeze the hardened state of social reality into a more fluid state that allows us to reimagine and reshape reality as needed.

(5) Facing our shadows and blind spots can be a source of transformation.

As the walls around us continue to crumble and collapse and as the challenges of our planetary emergency continue to be on the rise, leaders across institutions increasingly face situations that require them to look into the mirror of the collective — the mirror of the whole. What we see in the mirror in such situations may sometimes be difficult to accept. Think of it as the opposite of our polished social media selves. We may see and recognize a part of our self that was previously hidden in our blind spot. For example, for Germans that recognition may have to do with everything related to the Holocaust. For Americans it may have to do with the ethnocide against Native Americans, the theft of their land, and the slavery of people of African descent. For the Chinese, it may have to do with the ethnic violence against the Uighur Muslims. For Westerners, it has to do with colonialism and all its forms of violence — direct, structural, cultural.

As the pandemic has heightened our awareness of the shocking levels of societal inequality, and as the Black Lives Matter movement reminds us how these inequalities are rooted in the history of colonialism and collective trauma, we realize that the process of decolonizing our politics, our economies, and our minds is still at an early stage. Looking into the mirror and clearly seeing the shadows of our individual, institutional, and collective pasts can be challenging. And yet it’s precisely where the opportunity is; by recognizing and integrating those disconnected parts of our collective experience, we can turn them into a source of transformation and renewal. We can move, as my colleague Antoinette Klatzky puts it, “from pain to possibility.”

(6) Turning toward: You can’t transform a system unless you embrace it.

Let me summarize all of the above with one simple distinction. Whenever disruption happens, we have a choice: a choice between turning toward or turning away. Turning toward the challenge we face — or turning away from it. Turning toward and embracing reality — or turning away and denying reality.

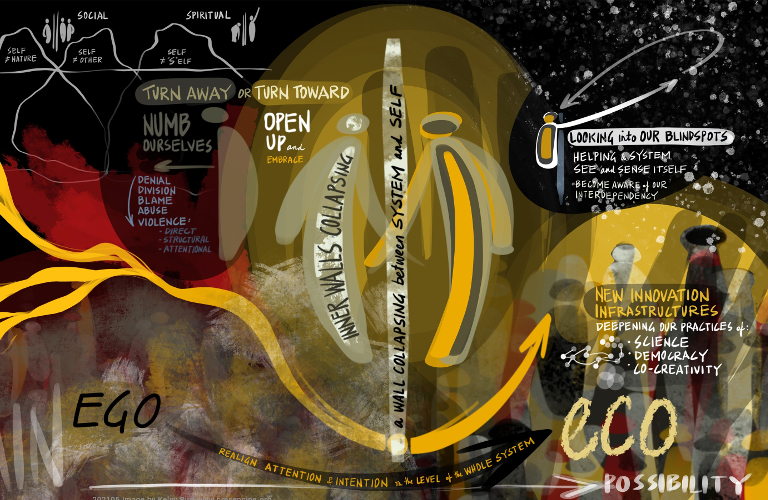

Figure 1: Turning toward or turning away: Presencing or absencing.

Figure 1 spells out that distinction. Turning toward is depicted on the lower arc of the visual: the cycle of seeing, sensing, and presencing. Turning away is depicted on the upper arc: the cycle of denial, de-sensing, delusion, and absencing.

Turning toward matters because you cannot transform a system unless you’re embracing it. The gesture of turning toward and embracing the world operates on cultivating three instruments: Open Mind, Open Heart, and Open Will (aka curiosity, compassion, and courage). The gesture of turning away and denying the world freezes these same instruments (the result is a Closed Mind, Closed Heart, and Closed Will — aka doubt, hate, and fear).

Figure 1 captures the deeper territory of systems change that collectively are going through in one way or another. It’s a tool that can help us to decipher the deeper evolutionary patterns of our time. As a system we collectively create results that almost no one wants and that results in massive levels of destruction and self-destruction (the arc of absencing). The arc of absencing depicts the inner making of these destructive forces that we are currently enacting on a planetary scale. The more upstream stages of that cycle include:

· denial: not seeing what is going on (as evidenced by Covid and climate denial)

· de-sensing: not feeling resonance with what I see (as amplified in social-media-based echo chambers)

· absencing: not connecting to my highest future possibility (as evidenced in the rampant spread of depression and anxiety disorder)

· blaming: inability to reflect, to see yourself through the eyes of another (much of our current discourse)

· destruction: of nature, of relationships, of societal structures, and eventually of self

Living in this decade of transformation means that these phenomena of absencing are never in short supply. Fueled by dark money in politics and amplified by Big Tech business models that rely on activating anger, hate, and fear, we have seen them spiraling almost out of control. How can we address these phenomena in ways that are transformative? How can we activate the deeper arc of presencing?

The key to activating these deeper learning and leadership capacities is to cultivate an inner stance that doesn’t “go to war” with a perceived external threat but that embraces reality by embodying what the late biologist Humberto Maturana called love. Love, according to Maturana, is “letting appear.” How can we develop methods and tools that cultivate these transformative interior conditions in individuals and in our larger systems?

As an action researcher at MIT and the Presencing Institute I have explored this question over the past two decades in many practical experiments. The concluding four learning points are grounded in that line of action inquiry.

(7) Societal evolution requires an upgrade of our operating systems.

The ego-to-eco shift that our planetary emergency is calling for requires an upgrade of society’s operating systems. Figure 2 outlines the stages of that evolutionary upgrade, using the examples of health, learning, food, finance, governance, and development.

Figure 2: Four stages of systems evolution, four operating systems

All of these sectors face a current reality that is largely anchored in a blend of 2.0 (output- and efficiency-centric) and 3.0 (outcome- and user-centric) ways of operating. But, to paraphrase Einstein, we cannot solve 4.0 challenges with 2.0 or 3.0 ways of thinking and operating. The true developmental challenge of our time is how to move from 2.0 & 3.0 to a 4.0 operating system that activates ecosystem awareness and co-creativity in all its elements.

The move to OS 4.0 is not a distant dream. It’s not a utopian ideology. It’s happening in the midst of our communities, though often at the margins of our larger systems. 4.0 ways of operating tend to show up first locally, and only later at national and international levels. You can see them in CSAs (Community Supported Agriculture), and in manifold collaborative efforts on the level of villages, cities, and regions. They tend to show up around the edges of collapsing systems before they take the center stage in world politics. So the future is already here, but we need to pay attention to it. The Paris Climate Agreement and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals are examples that embody first practical steps towards 4.0 governance on a global level.

Some of the most striking examples of 4.0 practices are common among Indigenous peoples. As my colleague Melanie Goodchild, founder of the Turtle Island Institute, puts it:

“We had 4.0 before contact and settler-colonialism wreaked havoc with our way of life so moving from OS 1.0 to 4.0 is not an evolution or linear progression for us because at one point all of our ancestors lived off the land. Instead it’s a returning to or a reawakening of those values that support 4.0.”

(8) Transformation journeys require support infrastructures.

Each journey of transformation requires innovation in support infrastructures. If we want to transform our economies, evolve our democracies, and reimagine our learning systems, we need to create innovations in infrastructure.

Figure 3 summarizes the discussion about our current conditions in terms of post-truth (spreading disinformation and doubt), post-democracy (amplifying architectures of separation) and post-humanity (fueling fanaticism and fear) and spells out the deeper leadership and learning capacities that we need to cultivate to transform these conditions:

· deepen our practice of science by integrating first-, second-, and third-person research.

· deepen our practice of democracy by building new civic infrastructures of dialogue and sensing of our systems from the edges.

· deepen our practice of entrepreneurship by activating action confidence.

Figure 3: Three current conditions, three capacities for transformation

These deeper learning and leadership capacities are being born and co-developed in countless communities and collaborative initiatives as we speak. For example, in the u.lab accelerator of the Presencing Institute we are this year working with 338 teams on initiatives for transformational change in their communities. As Manoj from India recounts:

“The moment those projects started shaping up, and the way people created their own core teams, the way the movement was happening, seeing the kind of leadership that was coming in… They were like, ‘oh wow, this is what is going to allow us to make the difference we want to make in the world.’”

(9) The biggest obstacle to actualizing our full transformative potential lies within ourselves.

What is the biggest obstacle to transforming our economies, deepening our democracies, and reshaping our learning environments? Is it the Big Tech companies that are tightening their grip on society (aka Surveillance Capitalism)? Is it the dark money that diverts the political process time and again? What is the most important obstacle? I have a hunch that neither one is the biggest culprit. The biggest obstacles to changing all the above are our inner voices of doubt, hate, and fear.

What I find interesting is that part of that skepticism seems to be intentionally induced. For example, years ago the fossil-fuel-funded climate-denial industry successfully shifted US public opinion against supporting a carbon tax. The key strategy employed by the climate-denial industry aimed at sowing doubt about the validity of climate science. It worked. So the voices of doubt can be intentionally amplified by each respective denial “industry.” When it comes to amplifying the voices of hate and fear its social media companies like Facebook who have built a trillion-dollar empire on a business model that largely relies on maximizing user engagement by activating the emotions of hate, anger, and fear.

Changing these things will require more than just throwing money at these problems (even though the Green New Deal-inspired trillion-dollar packages represent a great first step). The core of the transformation ahead lies in applying a whole new paradigm of thought to reimagining the main subsystems of our modern societies. These include:

I. Transforming our economies from ego to eco:

· from GDP to planetary and human wellbeing

· from linear to circular material flows

· from jobs to mission-driven entrepreneurship

· from extractive to regenerative capital

· from awareness- and creativity-reducing to awareness- and creativity-enhancing tech

· from private property to shared use and ownership

· from awareness-reducing to awareness-activating mechanisms of coordination and governance

II. Deepening our democracies by making them more distributed, dialogic, and direct:

· abolishing dark money

· abolishing the epistemological divide that companies like Facebook, Google, and Amazon perpetuate

· building new civic infrastructures that support distributed, dialogic, direct governance

III. Reimagining our learning environments by integrating head, heart, and hand.

Transforming our economies and advancing our democracies will only work to the degree that we can build new learning environments for whole-person and whole-systems learning in both education and across sectors and systems.

Which brings us to the final question.

OK, some of us will say, let’s assume that much of this might be possible — but honestly, do you really think that such a transformation of almost epic proportion could work? What would it actually take?

(10) The most important leverage point lies in democratizing transformation literacy.

It’s been said that the Renaissance was brought about by a core group of no more than 200 people. That undertaking transformed the world. What would it take today to co-ignite and actualize the potential for profound transformative change that many of us sense is in the air these days?

I believe it would take three or four things. First, you need inspired people. Maybe it’s more than 200. But if you have a relatively small group of truly committed people — almost anything is possible. The best group to work with of course is young people. Because young people, Gen Z, has the highest stakes in the future and the weakest attachment to the past. But in today’s context, you also need to build a powerful cross-generational web of change makers across sectors and regions.

Second, you need places and platforms. Any kind of movement that has created real change in society — be that around civil rights, gender, peace, or the environment — had a supporting infrastructure. That was true for Rosa Parks — the Highlander Folk School — as it was for the Eastern European civil rights movements, which often used the churches for creating these supportive infrastructures.

And third, you need enabling technologies. In the case of Rosa Parks they were the methods and tools of nonviolent resistance. What would be the functional equivalent of those today? I believe it would be a set of awareness-based social technologies that allow us to radically reconnect with ourselves, with each other, and with our planet. Methods and tools that are foundational to creating a vertical transformation literacy that is so much needed wherever we face the challenges of moving from 2.0 or 3.0 to 4.0 ways of organizing. That transformation literacy is the blind spot of our current educational systems. Addressing that blind spot with practical methods and tools would be the third element.

And the fourth element would be a globally distributed network of inspiring living examples and pioneering institutional prototypes that explore the future of 4.0 innovation by doing it.

If we add up these four components, what do we see? We see the prototype of a new university, a new school. That university or school of transformation focuses on democratizing the access to methods and tools for radically reconnecting with our planet, with each other, and with our own evolving selves as we reshape the societal structures that are collapsing now. Bringing such a Schoof of Transformation into being — designed for global replication at scale — is in my view the number one leverage point right now.

Over the past few weeks and months, my colleagues at the Presencing Institute and I have met with many innovators in education — from the heads the Department of Education at the OECD in Paris to policy makers, and university leaders and innovators who all are inspired by radically reimagining what education for human flourishing in this century could look like. At the same time, we have been working with hundreds of change makers across the UN system on accelerating the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and we are inspired by the radical honesty and humanity that is breathing through all these interrelated initiatives. As one of the participants, Christine from Barbados, put her experience of the current moment of disruption:

“I see how it all ties together…the good and the bad, all of us. I sense that we are all being exposed to crisis to push us all out of rooted spaces, to expose collective truth and to force collective change. I feel we cannot avoid the inevitable painful but necessary changes ahead.”

The journey ahead is not going to be easy. But if we are able to link both of these movements — the bottom-up movement that is arising now from all the different grassroot initiatives around the world, and the top-down efforts that begin to open up established institutions such as the UN, higher ed, or business to their surrounding ecosystems— then there is very little that we couldn’t do in a decade or two.

If you want to explore these and related ideas and practices more, feel free to visit the Presencing Institute or join our upcoming Global Forum.

I want to express my gratitude to Kelvy Bird for creating the image and to Becky Buell, Rachel Hentsch, Antoinette Klatzky, Katrin Kaufer, and Eva Pomeroy for commenting on the draft.