Déjà vu—the sudden insistent feeling that you’ve encountered the present moment before—can be one of the oddest of human experiences. Sometimes, though, it happens for perfectly prosaic reasons. Right now, as I look at headlines and certain other indicators, I’m having a very strong case of déjà vu for reasons that require only the simplest explanation. Sometimes, after all, you really have been there before.

Twenty years ago, for example, I could look back at the energy crises of the 1970s and see a certain pattern unfolding with great clarity. I’ll summarize the pattern for those of my readers who weren’t born yet at that time. All through the 1950s and 1960s, a handful of people had been warning that petroleum is a finite resource and that the breakneck extraction of petroleum at ever-rising rates was sooner or later going to slam face first into hard limits. They were of course dismissed as cranks by all right-thinking people. They were also correct.

In 1973, declining production from US oilfields combined with political instability in the Middle East to slap the United States with a sudden shortfall in petroleum. The government and the Fed responded clumsily, expanding the money supply, which drove up prices, not only for petroleum products but for everything that was made and shipped using petroleum—that is to say, pretty much everything bought and sold in the country. The result was stagflation. Meanwhile renewable-energy advocates convinced themselves that their time had come, and rushed a great many poorly conceived products to market, while the apocalypse lobby—those people who are constantly on the lookout for reasons to insist that everything is about to crash to ruin and we’re all going to die in the next few years—embraced the oil crisis as their cause du jour.

What happened, though, was neither apocalypse nor Ecotopia, but a return to stability with a high price tag. The higher price of oil covered the cost of projects that couldn’t have broken even before 1970. Oil fields in Alaska’s North Slope, the Gulf of Mexico, and the North Sea came online and drove the price of oil back down, and though it never went quite down to the price it had been before the crisis, it was close enough that people assumed the problem was over. Most of the renewable energy products launched during the crisis vanished from the market, though a few managed to hang on, and the apocalypse lobby found new things to emote about.

By 2001, the energy market had returned to a fair simulacrum of the conditions of the 1960s. The petroleum economy seemed to be chugging ahead, and only a handful of people were warning that petroleum is a finite resource and that the crisis had just been postponed. Once again, they were dismissed as cranks by all right-thinking people, and once again, they were correct. The first decade of the twenty-first century thus saw a repeat of the 1970s, except that the government and the Fed responded clumsily in the other direction, causing a bitter recession instead of stagflation. Once again, a great many poorly conceived renewable energy products were rushed to market, and the apocalypse lobby embraced peak oil as their latest reason to proclaim the imminent doom of everybody and everything.

Again, what happened instead was another return to stability, at a price. The sky-high price of oil made it economical to pursue projects that hadn’t been profitable before, and the Obama and Trump administrations doubled down on this by flooding the fracking industry with federal dollars under a variety of gimmicks. That drove the price of oil back down, and in the usual way, most of the renewable energy schemes collapsed of their own weight or lingered as zombies propped up by government subsidies, while the apocalypse lobby once again found something else to brandish as proof that we really will all be dead in a few years.

And now? Once again, only a handful of people are warning that petroleum is a finite resource and that fracking was a temporary fix at best, and all right-thinking people dismiss them as cranks. Meanwhile, over the last few years, the price of oil has been moving raggedly upwards, and even the price crash caused by the coronavirus shutdowns didn’t stop that movement for long. Déjà vu? It’s thick enough to cut with a knife.

The state of the fracking industry bears close examination here, not least because—as I’ve discussed in these essays rather more than once already—it’s one of the places where my predictions, like those of most other peak oil writers, turned out to be wrong. What misled us is easy enough to explain. There are very good reasons why extracting liquid fuels from shales by hydrofracturing is not an economically viable solution to the depletion of conventional petroleum reserves; that remains as true as it has ever been. What everyone in the peak oil scene missed was that this didn’t matter, because politics trumps economics.

Of all people, I should have caught onto this, because I was busy making the same argument in a different context. Longtime readers will recall the flurry of predictions that came out during the oil crisis of 2008-2009, insisting that the global economy was about to grind to a halt, leaving seven billion people to starve. I pointed out then that those predictions all assumed that the only response governments would have to a catastrophic market crisis was to sit on their hands saying in plaintive tones, “Whatever shall we do?” If the global economy had ground to a halt—as of course it never did—the political authorities could have intervened in dozens of effective ways, as they had done in plenty of economic crises over the previous century.

And of course that’s exactly the logic that drove the fracking boom. It’s quite true that extracting liquid fuels from shales by hydrofracturing is a miserably poor option in economic terms, and also in terms of net energy—that’s the equivalent in energy terms of profit, how much energy you have left after you subtract all the energy you had to consume to get it. From the standpoint of short term politics, which is the only kind of politics that matters in America today, those points were entirely irrelevant. All that mattered was that fracking could boost liquid fuel production for a few years and stave off a financial and political crisis, and so gimmicks were found to provide effectively unlimited credit to the fracking industry. If you can borrow as much money as you want and can just keep on rolling over the debts, anything is affordable.

Once again, anyone who points this out is dismissed as a crank by all right-thinking people. It’s become an element of the conventional wisdom, in fact, that what we face is not peak oil supply but peak oil demand. As more and more renewable energy sources come on line, the theory claims, demand for petroleum will drop until eventually production shuts down because no one wants crude oil any more. That would be a plausible theory, except for three things.So does that mean that the problem is solved, and no oil crisis will ever again rise up like the Shadow in Tolkien’s fantasies? Of course not. Just as the North Slope and North Sea oilfields depleted steadily once extraction began in earnest, US oil shale reserves are being depleted steadily. Oil is a finite resource, and the faster you pump it, the sooner it runs out. Gandalf had it right: “Always, after a defeat and a respite, the Shadow takes another shape and grows again”—and the ragged upward movements in the price of oil over the last few years is one of the warning signs that the current respite is drawing to a close.

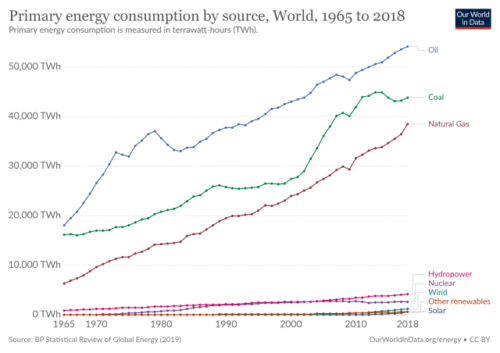

First of all, as the chart above shows, petroleum consumption has been increasing far more quickly than renewable energy sources have been coming online. This is one of the reasons why I remain distinctly suspicious of claims currently being flung around by green-energy advocates that solar and wind power have become the cheapest source of grid electricity. If they really were that cheap, utility companies—which are after all in business to make a profit—would be piling into them on their own nickel, replacing expensive natural gas plants right and left with solar and wind plants. Now in fact utility companies are expanding their solar and wind plants in a much more cautious way, and by and large seem to be doing so only to the extent that government mandates or subsidies push them into doing so, so it’s pretty clear that the rosy figures being brandished by green-energy advocates have about as much in common with reality as does any other kind of glossy advertising.

Second, if demand for petroleum was approaching a peak, given the ever-increasing supply of petroleum shown in the earlier chart, the price of oil would be dropping as a result of the law of supply and demand. That hasn’t happened. Quite the contrary, even though global production of liquid fuels reached an all-time high in 2019, oil prices moved raggedly upwards to that point, and have begun moving upwards again—raggedly, sure, and with plenty of sudden downside jolts, but still upwards, now that the impact of the coronavirus shutdowns has been priced in by the relevant markets. That shows that demand isn’t declining, and it isn’t even leveling off. It’s still rising—and that, in turn, disproves the theory of peak demand.

Yet there’s another factor at work here, and it’s the most important of all: Jevons’ Paradox. William Stanley Jevons was a British economist in the nineteenth century, one of the founders of the field of energy economics. In his 1866 book The Coal Question, he set out to make sense of the way that the price and production of fossil fuels are shaped by economic forces. One of the things he tackled was the seemingly plausible claim, widespread in his time, that the best way to make Britain’s huge but finite reserves of coal last as long as possible was to figure out ways to use it more efficiently.

Not so, said Jevons. What happens if consumers of coal use it more efficiently? They use less. What happens when this affects the market? The price of coal goes down. What happens then? People whose ability to use coal was constrained by price use more of it, and new uses are found for the newly cheap coal supply—and so the consumption of coal rises. He showed that using a fuel more efficiently simply guarantees that more of it will be used. What’s more, that’s what happens in the real world, and it’s happening around us right now.

What makes Jevons’ Paradox so deadly in the present situation is that adding new sources of supply to the energy mix has the same effect as making demand more efficient. That’s why it’s inaccurate to claim, as so many badly written histories do, that oil replaced coal. More coal gets burnt each year now than was burnt each year at the peak of the coal era; petroleum, by taking some of the demand that would otherwise drive up the price of coal, kept coal cheap and made it economical to use coal even more freely than before.

In exactly the same way, adding wind and solar to the energy mix doesn’t replace fossil fuels. As shown by the energy use chart above, it takes some of the demand that would otherwise drive up the price of fossil fuels, and thus keeps the price of fossil fuels lower than that would otherwise be. As a result, more fossil fuels get burnt.

(I should probably pause here to deal with the most common response to Jevons’ Paradox, which amounts to an anguished cry of “But that’s not fair!” No, it’s not fair, but it’s true anyway. The universe has never heard of human notions of fairness. If by some bizarre chance it did hear about those notions, it would simply shrug and keep on doing things the way it likes, since the universe cares about the preferences of one species of social primate on the third rock from a nondescript star in the suburbs of an ordinary galaxy about as much as you care about the preferences of the bacteria on the soles of your shoes. Does that makes you very, very upset? Here again, the universe will not notice, much less care. Screaming at the laws of nature may make you feel better temporarily, but it won’t budge them one iota.

(And if it seems paradoxical to you that a Druid who prays to pagan deities and practices ceremonial magic should be saying this in response to the behavior of people who by and large consider themselves practical-minded rationalists, trust me, the irony has not escaped my attention either. Thank you, and we now return to this week’s regularly scheduled post.)

So the theory of peak oil demand can be tossed in the same dumpster as phlogiston theory and Lysenkoist genetics. What we are facing instead, at some point in the next few years, is another brush with peak oil supply, and thus another spike in the price of petroleum. If it happens while the Biden administration is in office, to judge by the response of Biden’s handlers to the latest round of economic wobbles, we can probably expect a reprise of the 1970s strategy of expanding the money supply, and thus another round of stagflation followed by sky-high interest rates. If it happens under the next president, that’ll depend on which of the available range of bad options appeals most to Number 47 and his or her inner circle. One way or another, we can certainly expect serious economic and political troubles. We can also expect renewable energy advocates to bring another flurry of poorly conceived energy projects to market, and the apocalypse lobby to rediscover its fondness for petroleum depletion and fill the internet with another round of proclamations of imminent doom.

A few years further down the road, in turn, some new source of liquid fuels will be brought online in response to the higher prices then availble, most of the renewable energy products will vanish from the market because they don’t make economic sense, and the apocalypse lobby will forget all about petroleum depletion again in its eagerness to embrace the latest and most fashionable reason why we will all surely be dead by next Thursday—no, seriously, this time for real! Thereafter, only a handful of people will remember that petroleum is a finite resource, and they will of course once again be dismissed as cranks by all right-thinking people—until the next price spike hits.

Does this mean that petroleum depletion doesn’t matter? No, that’s not at all what it means—but petroleum depletion matters in a way that doesn’t fit the narratives that our culture likes to use when talking or thinking about the future. Every round of the cycle we’ve discussed in this post has driven a sharp decline in standards of living for most Americans, and despite a great deal of handwaving and statistical manipulation, those declines have not been made up in the intervals of relarive stability that followed each crisis. Most Americans are much poorer today, in terms of the quality and quantity of goods and services they can purchase with the incomes they are able to earn, than their equivalents before 1973, and noticeably poorer in the same terms than their equivalents before 2008. They will be poorer still when the next round of crisis is over.

Furthermore, the built environment and public infrastructure of the US have suffered equally sharp declines in the same stairstep fashion. It’s safe to assume that the aftermath of the next crisis will see another step down of roughly the same type and magnitude. No doubt another round of handwaving and statistical manipulation will be used to insist that the declines didn’t happen, don’t matter, and are the fault of the people who are suffering from them—those have been the usual response to economic contraction from the chattering classes for a good many decades now. Yet the ongoing decline of the American economy and the ongoing disintegration of our built environment and infrastructure can’t be magicked away by such tactics.

The unlearned lesson of petroleum depletion can be summed up very neatly: sure, you can find another source of liquid fuel to replace the fields that you’ve pumped dry, but it’s going to cost you—and the cost will go up, and up, and up with each hard encounter with the finite nature of fossil fuel resoruces. So far the price has included driving large parts of the American working class down to Third World levels of impoverishment and immiseration, and the accelerating layoffs and plunging income in many formerly middle class careers suggest that the next step down will see the lower end of the managerial classes cut loose to sink down to the same level.

I therefore expect the next decade of so of politics and culture in the United States to be twisted into strange shapes by the frantic efforts of the downwardly mobile to claw their way back up to positions of privilege that aren’t there any more. Politicians and pundits will doubtless come up with any number of ways to exploit those efforts. In the end, however, it’ll all be wasted breath, because the process of decline cannot be reversed.

The extravagant prosperity we had in America in the recent past, after all, existed for two reasons. The first was the accident of geology that blessed the United States with gargantuan petroleum reserves, many of them very close to the surface and easy to extract. That made it possible for the United States in the mid-twentieth century to pump more petroleum out of the ground than the rest of the world combined. The extraordinary bonanza of unearned wealth provided by that torrent of black gold, together with bare-knuckle international politics during and after the Second World War, created a temporary situation in which the United States had 50% of world GDP, and the 5% of the world’s population that lived in this country had at its disposal a third of the world’s manufactured products and a quarter of its energy.

That was never sustainable in the first place, and the attempts that were made to prolong it after it stopped making any kind of economic sense simply pushed problems further down the road while doing nothing to solve them. Now the consequences of those short-term decisions are piling up, the underlying depletion of fossil fuel reserves are continuing, and the consequences of all that fossil fuel consumption are driving disruptive changes in the global biosphere that are imposing rising costs of their own. It’s a messy situation.

It’s also one that every other civilization has encountered in its own way once it finished its era of expansion, depleted whatever resource base was central to its rise, and began to stumble down the long ragged slope of its future. The experiences of people living through the same process in earlier ages shows that there are constructive options available, for those who are willing to be dismissed as cranks by all right-thinking people. I’ve discussed some of those choices already, here and in my previous blog (which, by the way, you can get collected in print or e-book format here if you’re interested). We’ll be discussing more of them in the future—and if those discussions give you a sense of déjà vu, dear reader, then you’re paying attention, because we really have been here before.

Teaser photo credit: By Griffiths, Samuel, editor of "The London Iron Trade Exchange" – https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14761790294/Source book page: https://archive.org/stream/griffithsguideto00grif/griffithsguideto00grif#page/n110/mode/1up, No restrictions, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44169686