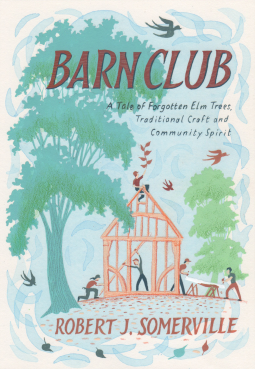

While it’s true that machines can make life easier, they don’t necessarily make it better. Robert Somerville, author of Barn Club, understood this fact. That’s why he decided to gather a team of volunteers to come together and build a barn the old fashioned way – with a little sweat, tears, and his hands.

While it’s true that machines can make life easier, they don’t necessarily make it better. Robert Somerville, author of Barn Club, understood this fact. That’s why he decided to gather a team of volunteers to come together and build a barn the old fashioned way – with a little sweat, tears, and his hands.

The following is an excerpt from Barn Club: A Tale of Forgotten Elm Trees, Traditional Craft and Community Spirit by Robert Somerville (Chelsea Green Publishing, March 2021) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.

(All photography curtesy of Robert Somerville unless otherwise noted.)

Inspired by the sight of the Great Barn at Wallington, an ancient elm barn on a farm near to my home, I set out to follow the process of making that had been undertaken by people of a previous era; before the days of power tools and mass manufacture. I wanted to follow their footsteps. I wanted to learn firsthand why they chose elm wood rather than the customary oak. My vision was to incorporate as much as possible of the process that those carpenters undertook to be able to understand their challenges and their joys. From the beginning of this project, friends, neighbours and even people I had never met before were attracted to the idea, and offered to come and help for free. Barn Club was born out of this spontaneous, shared willingness to engage with my vision and be part of the event. The emergence of this sort of community spirit has been both heart-warming and humbling. In my life as a designer and carpenter, I have always assumed that you needed to pay people to do stuff, whereas the volunteers see things differently. Why would anyone choose to come and work for nothing? It’s a question I kept asking myself. Adrian Toole, a maverick cyclist, enthusiastic green campaigner and also someone who saw the project from start to finish, commented:

My mother could not understand it. ‘Why do you keep going when he doesn’t pay you?’ she asked time and again. The answer was that I knew those days working with the wood were unique life experiences and I appreciated the laughter, the teamwork, the training and, of course, the lunches!

The volunteers made their livings across a broad range of professions, from accountancy to bicycle safety instruction. For many there was a strong desire to be doing something other than sit at a desk in front of a computer; Barn Club is a really good relief from digital overload. Making something beautiful is also massively satisfying. Most importantly, timber framing done in a traditional way is accessible to everyone. The volunteers were able to fully take part with no prior carpentry knowledge. They picked up the skills whilst using hand tools just as novices would have done in previous times. Nick Exley, a retired dentist, with a wind-blown fitness and a love of the outdoors, describes his experience:

Once I had completed Robert’s carpentry course, that initiation into the ‘mysterious arts’ of timber framing, I very quickly began to look forward to my days working on the project. I have always enjoyed working in small teams and this didn’t disappoint. It was happy and without pressure because of the concept of being volunteers and not on a strict deadline to get the job done. There were moments of bafflement when we would be working in pairs and that unspoken glance would say, ‘Do you understand this?’ And the look back said, ‘No, I don’t. Do you?’ Even in the showery weather we could huddle in the lean-to canteen for a tea break and put the world to rights. But somehow we always got there in the end, and as each week went by there slowly emerged possibly the most beautiful building I have ever seen. But of course, that’s because I could go round and say, ‘I did that bit!’

There is no doubt at all in my mind that resisting the lure of power tools was key to finding new possibilities for working with volunteers, and therefore a new approach to working within contemporary woodwork culture. Volunteers need to work in a safe environment, and power tools are essentially unsafe. To be able to work with inexperienced people, hand tools are the answer. As Joel Hendry, a leading timber frame carpenter, puts it, ‘When you start using a machine morticer, you pass a threshold. Before long the way you work, the type of joints that you make and the whole circumstance of the framing yard changes to suit the machine’s needs. In the worst case, a carpenter can become little more than an attachment to a power tool.’ When I asked Joel why he liked timber framing by hand he replied, ‘The joy of using hand tools is that it needs hand, eye and brain, which always feels good.’ Joel isn’t an advocate of a power-tool-free world, but by having a foot in each camp he acknowledges that there is a price to pay when machines predominate. As a highly skilled individual, he abhors the treadmill of nonstop, endless, frame factory production using power equipment. Why would anyone volunteer to do that?

The revival of timber framing in England is ongoing and expanding, but that hasn’t always been the case.

By the early twentieth century, the scribing and cutting of local timbers, then fixing them together with wooden pegs, had nearly vanished as a way of building. Along with this decline went a loss of knowledge. Two notable exceptions are the timber frame for Bedales school Memorial Library by Ernest Gimson and Geoffrey Lupton in 1921, and the new hammer beam roof of the Great Hall at Dartington Hall estate, by William Weir and Jack Goode in 1933. These two buildings stand out not just for being large timber frame projects based on what had by then become bygone traditions, but because the architects themselves were working craftsmen.

The current revival began about forty years ago, and the Carpenters’ Fellowship was established in the UK at the beginning of the twenty-first century. There are now many companies and individual framers spread across the country producing timber frames for houses, garden studios and wedding venues, and where I live there is a thriving fashion for porches to embellish front doorways. The demand for chunky, bare oak frames with an aura of craftsmanship hasn’t diminished in our modern era. At the same time as the appeal of post-and-beam carpentry has expanded, the physical process of producing the frames is increasingly mechanised, efficient and automated. In an age of digital industrialism, this is a good moment to review what is at the core of the craft to ensure that the important things don’t get eclipsed.

My memories of the early days of the timber frame revival in England are of a shared passion for wood, for good-quality tools and for the discovery of an obscure form of carpentry. And, most importantly, I remember the fun of getting together and making a project into a joyful social gathering. Carpenters would travel around the country to work on different frames and for some particular projects a gathering would be arranged. These became affectionately known as ‘rendezvous’ projects, reflecting the spirit of camaraderie among timber framers. Volunteer carpenters would arrive en masse and stay for a week or so until the frame was completed. This spirit lives on today, and rendezvous projects occur across Europe and North America, particularly through the efforts of the Carpenters’ Fellowship in the UK, the Timber Framers Guild in the US and an international group called Charpentiers sans Frontières (Carpenters without Borders) based in France.

Although not unique to timber framing, the atmosphere of generosity and goodwill are something that surrounds the craft. In the late 1990s I travelled across the US and found the same thing happening there. I was warmly received by timber framers and their families, from architect and builder Jack Sobon on the East Coast to the late Merle Adams of Big Timberworks in the Northwest. Those weeks spent observing their different business models and experiencing different rural cultures and carpentry traditions inspired me deeply and changed the course of my career. I wasn’t travelling as a working journeyman, though those ancient traditions of medieval guild apprenticeships still survive in continental Europe today. Apprentices still travel between carpentry businesses as part of the training, carrying only their tools and often wearing traditional flared black corduroy trousers. This aspect of travel and exposure to diverse cultural experiences is thought to be an essential part of what it means to be a compagnon du devoir – companion of duty – within the French system of travelling craft apprentices. Learning a craft involves so much more than acquiring a skill or operating machinery to produce a product. In the past this was not only understood, it was fundamental. The compagnon would be on a personal journey of self-discovery that had moral dimensions as well. Learning a craft was meant to be a life-changing experience.

Mihai Vatajelu, a timber framer who runs a construction company in London, has taken part in the gatherings of the Charpentiers sans Frontières and came to volunteer at Churchfield Farm. Like so many people I talk to, he has grandparents or great-grandparents who were carpenters. He also feels the tug of wanting to work in a more meaningful way with wood:

I love timber framing. My best memories of the Carley Barn are the mornings at the start of the project, especially the cold ones; light snow on the timber, and then warming up through the physical effort of the carpentry. Working with wood the traditional way seemed to trigger in me a sleeping gene that, as a Romanian, I’m sure must have been passed on to me from my grandfather, Simon Vatajelu. He was a forester in charge of a large birch tree forest. I’m trying to find a way that makes sense in combining the new way of life dominated by technology with the traditional way. Always choosing technology will only make the old ways disappear.

I believe that when we think of making something and we set out to gather the materials and the wherewithal to do it, we stand at a fork in the road. On one side we see a well-trodden path of power tools and technology, on the other, a path of handwork, far less travelled in our day and age.

By taking this second path, as we did to make the Carley Barn, a different world opened up.

Immediately, in the absence of machine noise, you can hear what you are doing as well as see it. You can hear background birdsong or the soughing of the wind in the branches of trees overhead as you work. If you are able to source your raw material from your immediate natural surroundings, as a woodworker can, knowledge of the natural world seeps into you unconsciously. This connection and dependence on nature changes how you live. A craft that is rooted in its materials inevitably places you within the natural world rather than being simply an observer of nature. You develop a personal relationship with the landscape and the lives of animals, insects, birds and plants within it. This reaching out into the natural world to find the essentials of your craft occasionally leads to feelings of sublime happiness. It is not surprising really, as every single cell in our body is part of nature and is completely at home when we walk through a wood, stare at the sky or watch the flowing of a river. We have subliminal capacity in these settings, which fires up particular intuitive knowing. We begin to feel very much at ease and at one with the landscape. An uncanny knack of finding what you are searching for develops. In my case it appears through love of trees. Finding elms seems second nature.

Further along this ‘less well-trodden path’ a sort of intimacy grows, which is felt through the close partnership of hand tools, our hands and the material itself. Sometimes when you are working, the distinctions and boundaries between these three break down and you lose all sense of which is guiding and which is following: something is simply appearing through itself. This level of surrender to the process has elegance and grace, which I feel certain is a shared experience amongst many crafts. A craft is more than a hobby or a trade, it is a way of giving life to things.

Teaser photo credit: Joints in an ancient French roof; the wooden pegs hold the mortise and tenon joinery together. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chevilles_en_bois_dans_une_charpente_ancienne.jpg#/media/File:Chevilles_en_bois_dans_une_charpente_ancienne.jpg