If the Perseverance rover now exploring Mars finds substantial deposits of water under the Martian soil, perhaps it can send some to Taiwan. Taiwan—where so many of the world’s semiconductors are manufactured, but probably not the ones guiding the Martian rover—is suffering its worst drought in 67 years. The Taiwanese drought illustrates converging risks that involve climate change, geographic concentration of a critical industry, outsourcing, international tensions and supply chain fragility.

The drought has been very bad for those Taiwanese farmers affected by a shutoff of irrigation water. So far the shutoff affects only 19,000 hectares (46,950 acres) or 6 percent of all irrigated land.

But now the drought is threatening a mainstay of the Taiwanese economy, semiconductor production. This matters to the rest of world because the island nation of Taiwan is home to more than 20 percent of the world’s semiconductor manufacturing capacity, the largest percentage located in any one country.

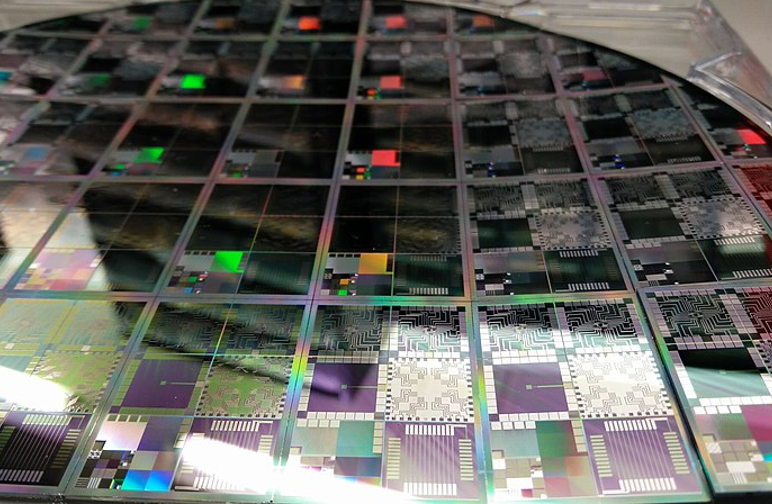

Semiconductors, the basis of practically all communications and computing infrastructure, require large amounts of water for their manufacture. The water is ultra-purified and used to clean the chips during assembly. Even the tiniest bit of dust or other foreign matter can destroy chip performance. It’s difficult to find recent figures on exactly how much water is used. One source claims that approximately 2,200 gallons of water are used to manufacture a 30-centimeter (12-inch) silicon wafer. That figure might very well be less today as manufacturers try to recycle some of their water.

But still, those manufacturers continue to use a lot of water. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, Taiwan’s industry leader and the second largest manufacturer of semiconductors in the world, consumes 156,000 tons of water PER DAY, according to Bloomberg. In the northern region of the country, the company accounts for more than 10 percent of the water usage.

The country of Taiwan and its people have become very adept at making semiconductors. And, they have been able to produce high-quality chips at competitive prices. It’s no wonder that many companies at the center of the tech and computer revolution have outsourced this task to Taiwan.

Few people involved in the decision imagined a day when there might not be enough water in Taiwan to support such manufacturing. After all, Taiwan is an island nation in the Western Pacific intersecting the Tropic of Cancer and it averages 100 inches of rain per year. Some of that rain comes from regularly occurring typhoons that hit the island more than three times a year on average.

But not a single typhoon landed in Taiwan in 2020. One Taiwanese climate scientist explained to Reuters that “high-pressure zones merging in the upper atmosphere over the Pacific and Southeast Asia” are “‘building a protective wall around Taiwan’ and driving typhoons north towards Japan and South Korea.” This development is likely a result of climate change which is expected to cut in half the number of yearly typhoons in Taiwan’s region of the Pacific by the end of the century.

All of this would be less concerning to those around the world were it not for Taiwan’s central role in providing a key ingredient for the infrastructure of the modern information age .

That concern is growing for other reasons as well. Tensions between Taiwan and China have resurfaced the ever-simmering issue of China’s claim that Taiwan is part of the People’s Republic of China. Chinese military jets recently flew through areas monitored by Taiwan’s air defenses. The Chinese government released a statement saying that any declaration by Taiwan that it is an independent state would mean war.

There have been such threats before. But events unfolding in Hong Kong provide a more ominous backdrop to the latest spat between Taiwan and China.

Yet another development has also highlighted the fragility of current arrangements. A sudden shortage of computer chips for automotive production has forced some assembly lines to shut down. Could other industries be next?

The shortage points up the vulnerability of so-called just-in-time manufacturing, in which components needed for assembly are delivered just in time for their use. Delivery trucks carrying parts essentially become rolling warehouses for manufacturers. It’s a system that works until it is doesn’t.

As I explained in a recent piece:

Ostensibly, the reason for this hiccup is that automakers curtailed production dramatically at the beginning of the pandemic. Chip producers then found a blistering market for their chips in computers, televisions and other devices that now homebound workers were ordering in unprecedented quantities. Auto sales have rebounded far sooner than expected, but the chip producers have pledged their production to other industries.

Two automakers who stockpiled the chips just in case now have the upper hand.

Semiconductors are not the only example of difficulties arising from the global system we have created. The supply of rare earths, a group of key metals essential to electronics and renewable energy, now come predominately from China which has threatened to reduce its exports in retaliation for hostile U.S. trade and military actions.

Which brings me back to the Perseverance rover on Mars. The rover is built for self-sufficiency and resilience. It has to be. There are no humans who can make a service call to Mars to fix it if something goes wrong. And, it turns out that the semiconductors that make up its brain come in the form of a PowerPC processor.

Longtime Apple computer users will be scratching their heads wondering why a processor used in a 1998 Apple computer would be controlling the latest Mars rover. NASA chose this processor on purpose because it is so reliable and reliability is what must come first on such missions.

Perhaps the managers of today’s global logistics system still have time to prove that there is intelligent life on Earth by learning something from the Perseverance rover about how we might do things better here on our planet.

Photograph: A 12-inch wafer of microelectronic testbeds (2017). Dr. Hugh Manning via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Semiconductor_Wafer_of_Microelectronics.jpg