Last March, the pandemic forced the world’s transportation systems to come to a dramatic halt. After months of lockdowns, their former passengers, champing at the bit to get back to ‘normal’, now sift through travel brochures with longing. Dawid Juraszek stands before the Bosphorus Strait and reflects on how the ancient conqueror, Xerxes once considered human destiny, and on a parallel modern drive to keep moving at all costs.

Brooklyn Ferry, City of New York, [c1909?] Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. USA

On what my memory archived as a clear summer day I stand at the edge of a continental landmass, contemplating all the means that brought me here and promise to take me anywhere. Ships, boats, ferries, yachts on the face of the waters; cars, trucks, and motorbikes on bridges above; subway trains invisible below; airplanes. Tireless and purposeful in ‘getting there’, natural barriers matter little to them – to us.

Immersed in the Earth to the point of not seeing it, I can always pinpoint a proximate cause for going somewhere, anywhere. After all, moving through space is what human beings do, and even when staying put, trapped by circumstances of our own or somebody else’s making, we’re thinking about it, planning, dreaming, worrying. Sometimes we anticipate future travelling while travelling, unable to connect with the present moment and with ourselves in it, separated from what is by what we think about what is.

But, though it’s easy to come up with well-rehearsed explanations for every instance of this constant movement, none of them reveals the ultimate cause.

In the midst of an age that propelled all that fervent rush to new heights, Walt Whitman asked:

‘What is the count of the scores or hundreds of years between us?’

His confidence in the shape of future that exudes from ‘Crossing Brooklyn Ferry’ is breath-taking: how could it not be that ‘so many hundred years hence’ there would still be passengers to ‘enjoy the sunset, the pouring-in of the flood-tide, the falling-back to the sea of the ebb-tide’? And yet the 19th century ferry service Whitman immortalised in his free-floating poem has long been eclipsed by bridges and subway lines. For the species that tamed fire, a single way of getting from A to B is hardly enough.

If human ingenuity were a story, one of its main motifs would be transportation. Creatures of land by birth, we have transcended our limitations, reaching across air and water, beyond our own biosphere. The world appears to have no edges off which we could fall into the abyss. Flat-Earthism may have been relegated to the fringes but another myth lies at the very core of who we have become as a civilisation: perpetual motion.

I step on board. The ferry reeks of diesel fumes, its hull vibrating in concert with the grinding engine noise on the way from one continent to another. It’s not Brooklyn. It’s the Bosporus, and in crossing it I’m enabled by energies born long before there was any Europe to be torn off from Asia or any Istanbul to be split down the middle, its population of 15 million mobilised to stitch up the gaping divide through fossil fuel-powered travel.

Why am I even taking this ferry? When, nearly a hundred years ago, George Leigh Mallory was asked about why he wanted to climb Mount Everest, he famously replied ‘Because it’s there.’ The ferry is there, too. So is every bus, train, plane. So is anything. Far from being a cliché, these words tell us more about what we’ve become than we wish to know. And recalling them right here, right now tells me the most.

Bosphorus Strait

*

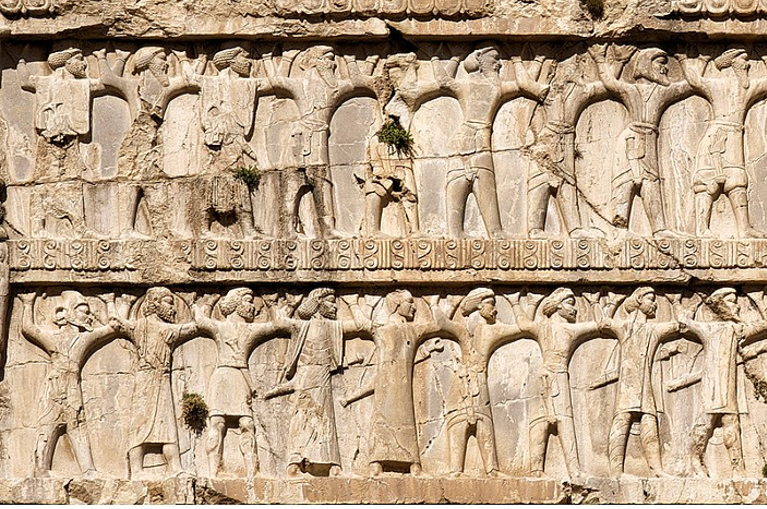

‘The similitudes of the past and those of the future’ that Whitman invoked strike me hard 250 kilometres south-west of Istanbul, away from the Black Sea, across the Sea of Marmara, towards the Aegean. Another narrow stretch of water that tears and splits, the Hellespont – or the Dardanelles, as it’s now called – is where two and a half millennia ago Xerxes beheld his forces of millions and his fleet of thousands, land and water swarming with humanity.

The Persian King of Kings smiled at first, Herodotus reports. Hellas lay within his grasp, the strait was no match for his logistical prowess, glory beckoned. But then something gave way and he wept. Wise old Artabanus asked him why.

Xerxes could have shaken off this awkward moment, dismissed the question and pressed on with the business of empire-building as if nothing had happened. He didn’t. Instead, he blurted out that ‘a sudden pity’ came over him as he ‘thought of the shortness of man’s life, and considered that of all this host, so numerous as it is, not one will be alive when a hundred years are gone by.’

A hundred years. Average life expectancy at birth may have shot up since the Graeco-Persian Wars, but Xerxes’ sudden realisation has never been more to the point than now that the naïve charm of the edges of the Earth has been replaced by the brutal chart of planetary boundaries. Looking up, I can’t help but think of the forces steadily gathering in the blue of the sky, powerfully indifferent to our timetables, targets, and treaties.

World-weary and war-wary Artabanus played along with Xerxes’ outburst:

‘Short as our time is, there is no man, whether it be here among this multitude or elsewhere, who is so happy, as not to have felt the wish – I will not say once, but full many a time – that he were dead rather than alive. Calamities fall upon us; sicknesses vex and harass us, and make life, short though it be, to appear long.’

And so they stood – two powerful Persians with the known world at their feet – above a heaving sea of human bodies ready for battle. Me? I’m standing with a UV umbrella over my head, a dazzling sea of toxic water before me. Yet we are all gripped by the same insight. Thousands of years after Herodotus, in a different language and on another continent, David Benatar summed it up thus: ‘coming into existence is always a serious harm.’

But there is much in that exchange between Xerxes and Artabanus that Benatar, the soft-spoken philosopher of antinatalism, would question. By ‘death’ Artabanus seems to imply non-existence as synonymous with freedom from calamities and sicknesses. But non-existence in the wake of living and non-existence that living never followed are two different things separated by a sea of suffering. Artabanus attempts to give the whole matter an uplifting spin by concluding that ‘death, through the wretchedness of our life, is a most sweet refuge’, but isn’t that refuge predicated on the wretchedness in the first place? Worse still, isn’t its ‘sweetness’ a delusion? As Benatar observes, real predicaments are intractable:

‘If one is in a predicament from which there is a costless (or a low-cost) escape, one is not really in a predicament.’

Artabanus decries life’s calamities and sicknesses while confidently pointing to an escape hatch that isn’t there.

‘Death might deliver us from suffering, but annihilation’, Benatar argues, ‘is an extremely costly “solution” and thus only deepens the predicament.’

Given all that, and given what’s coming, an antinatalist repeats Whitman’s line ‘I consider’d long and seriously of you before you were born’ but instead of exhilaration at the prospect of new lives being brought into existence to experience what all have experienced since the beginning of time, decides that the only ethical way forward is not to create new life at all. What would the King of Kings, dedicated as he was to leaving ‘a memorial behind him to posterity’, make of that?

*

Our predicament is about more than an individual coming to see the ‘wretchedness’ of their life. For all the recent talk about climate ‘crisis’, ‘emergency’, ‘catastrophe’, and ‘breakdown’, we are being deceived by these and other words we use. Even with such appropriately ramped-up vocabulary, there still remains a veil of separation between the cause and effect, action and reaction. We have a history of keeping distance in this way. The environmentalist and author George Marshall recounts how Sheldon Kinsel, a lawyer with the National Wildlife Federation, when testifying about climate change (or as he called it ‘climate shift’) during a congressional hearing in 1977, declared that ‘other environmental problems pale beside it’. A seemingly innocent pronouncement, it helped ensure that a threat that demanded a comprehensive approach and universal cooperation on the global scale was relegated to being an issue for the environmental movement only, which was all that was needed to allow those with leverage – government, business, media – to put it aside as something to deal with later. And now here we are, standing at the edge.

The predicament we find ourselves in is about the biosphere we rely on, the civilisation we take for granted, and the survival of our own species. ‘Climate’ and ‘the environment’ are words and concepts that offer us a convenient excuse, however thin, to keep thinking that it’s not directly about us yet. They encourage us to claim we can ‘save the planet’, as if we were some all-powerful beings on the outside looking in, instead of what we really are: Oblivious passengers on the back of a wild beast hurtling through the outer space, brutally spurring it on even as it prepares to throw us off. Nothing short of ‘survival crisis’ will do.

That’s not the kind of insight we tend to develop when we board flights or ferries – nor when we make our way through the dazzling sea of opportunities and offers. How could it be otherwise? Ceaseless motion silences such thoughts, constant distraction ridicules them, captive cognition ignores them. So much is there for the taking, before our eyes, within our grasp, beguiling our minds, whether we can afford it or not. Consumption and entertainment are poor substitutes for what truly matters – but they provide a powerful illusion that it’s them that do.

Having exchanged bracing profundities with Artabanus, Xerxes got back to work. He had the strait bridged and the sea given 300 lashes when it rose in protest. Barriers were meant to be powered through. Still are: the infrastructure corridors and transportation links that brought me to the Turkish shores fulfil the reigning desire for conquest of nature, so forcefully expressed already in the Biblical command for mankind to have dominion over the living world, and echoed by Mallory himself before his fatal third attempt to climb Everest, when he justified his mountaineering exploits as a part of ‘man’s desire to conquer the universe’. To say that ‘we’ followed that command to the letter would be unfair – after all, for most of human history most humans did no such thing – but given the sheer weight of modernity upon the Earth, we might as well have. And what that paradigm of conquest and domination is sourced from and powered with are the attractive forces of addictive utility accumulated over eons that we are now squandering in decades.

I took the ferry across the strait. And back, too. I took the bus, the train, and the plane. I took them because they were there for me to take; because I could. That’s it and that’s all. Time and again I tried to really connect with my own seemingly negligible and yet absolutely undeniable contribution to what we have unleashed. All I found was glimpses of the actual reality, so efficiently tiled over with the collectively constructed one that we call ‘everyday life’. In our minds the latter takes precedence over the former, even as it is the former that makes the latter possible, not the other way round. The current paradigm features inbuilt attention-diverting processes that shut down any meaningful contemplation of its own fatal flaws, let alone resistance to it. Near impossible to break out of, it is at each and every turn breaking down the foundations of all that it promises to deliver.

The efficiency of this compartmentalisation is staggering – and cross-generational. ‘Fly on, sea-birds!’ urges Whitman towards the end of the poem, ‘fly sideways, or wheel in large circles high in the air’, only to cheer a few lines later: ‘Burn high your fires, foundry chimneys! cast black shadows at nightfall! cast red and yellow light over the tops of the houses!’ as if these two visions were coequal or compatible. But he couldn’t know, could he?

*

What brought me here and brought all of us to the present predicament is the brute force of carbon-powered hubris armed in insulating words and concepts. It has entrenched itself in our modern globalised worldview to the point of appearing to be our birthright. The illusions of total control over the natural world have seduced too many; the more you believe in adapting ourselves to the rhythms of natural systems rather than forcing those systems to adapt to us, the less power you have in the systems of modern civilisation. And looking at the traffic that never ceases crossing the Bosporus and the Dardanelles in all directions, I think of the world a hundred years from now. What I can see around me gives every impression of being unstoppable, and yet I know it cannot go on. The default narrative has for a long time been that prosperity lies within our grasp, obstacles are no match for our technological prowess, and glory beckons. But it’s increasingly clear that more lashes won’t do.

‘And you that shall cross from shore to shore years hence, are more to me, and more in my meditations, than you might suppose’,

Whitman sings of himself and of us all. Lost in the lives we’re made to live, we forget to meditate on life itself. Yet natural barriers do matter to us, and to those that come after us, whether we’re aware of that yet or not. There is no easy fix, no escape hatch at hand, only stories that we tell each other to justify or dismiss real efforts. We have much less than a hundred years to tell the right ones.

Writing an essay like this one on board a ferry or a plane feels meaningful, poignant, visceral – precisely because of where it’s written. There is hardly any carbon-innocent means left in the Anthropocene by which anything could be done, writing included. But you need to do something and begin somewhere. Giving way to what you feel when you suddenly catch a glimpse of the real edges of the Earth is a start. If all the wrong things are there for you to take in one way or another, so are the right things. The process of your own Deep Adaptation to the inevitable – through answering for yourself how you can retain what you really need, what you have to relinquish in order not to make things worse, and what you should restore to help with all that’s coming your way – will follow.

Or not. After all, Xerxes marched on.

Benatar, D. Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence. Oxford University Press 2008.

Benatar, D. The Human Predicament: A Candid Guide to Life’s Biggest Questions. Oxford University Press 2017.

Herodotus. Histories. Translated by George Rawlinson. Wordsworth Editions 1996.

Marshall, G. Don’t Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change. Bloomsbury 2014.

Teaser photo credit: By A.Davey – This file has been extracted from another file: Xerxes detail ethnicities.jpg, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=73682194