Originally published at Literary Review

How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need

How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need

By Bill Gates

(Knopf / Allen Lane 272pp)

Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future

Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future

By Elizabeth Kolbert

(Crown / The Bodley Head 256pp)

Some readers may question the value of a book on climate change by Bill Gates, who made his fortune in the computer software business. Yet Gates has a long history of philanthropic work and engagement in discussions about the environment, and he has the resources both to gather relevant data and to pick the brains of experts. His book is a highly readable summary of mainstream thinking on ways to prevent the worst. His essential conclusion is that in order to avert climate disaster we need to get to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, deploy existing lower-emission forms of energy (like solar and wind power) ‘faster and smarter’, and ‘create and roll out breakthrough technologies that can take us the rest of the way’.

Emissions can be sorted into two baskets: electricity (which accounts for about a quarter of emissions) and everything else. The burning of fossil fuels accounts for two thirds of all electricity generated worldwide. Even though solar and wind power are getting cheaper by the year, they suffer from intermittency: dealing with diurnal and seasonal fluctuations will be complex, requiring energy storage, redundant generation capacity (i.e., installing far more generators than will be needed on sunny, windy days) and demand management. We will therefore need additional electricity sources. Gates is in favour of nuclear power. ‘It’s the only carbon-free energy source that can deliver power day and night, through every season, almost anywhere on earth’, he writes, while also pointing out how little material it uses in comparison to other sources of energy. Nevertheless he acknowledges that it is expensive and that issues of dealing with radioactive waste remain unresolved. He has invested hundreds of millions of dollars in a company that is creating designs for a next generation of reactors – but these won’t be ready to deploy for many years.

Then there’s everything else: emissions from manufacturing, buildings, transportation and agriculture. Electric cars are proliferating, but not electric cargo ships or airliners. High-heat industrial processes (like making cement and glass) will likewise be difficult or expensive to electrify. For these, we’ll need new low-carbon fuels, which will be costlier than oil or natural gas. Altogether, a host of what Gates calls ‘green premiums’ will be entailed, imposing higher expenses on governments, industries and households.

Much of this book is a plea for more technological innovation to remove carbon from the atmosphere and reduce green premiums. ‘Show me a problem, and I’ll look for technology to fix it,’ Gates says. He does concede that while technofixes are ‘necessary’, they are ‘not sufficient’, but his exploration of non-tech strategies is mostly restricted to government efforts to incentivise innovation. In contrast, some European environmentalists and economists are discussing ‘degrowth’ as a partial solution to climate change. After all, economic growth makes the problem continually harder to solve, while also driving resource depletion and loss of wild habitat. The only point at which Gates is sympathetic to the idea of ‘using less’ is in his discussion of load shifting (timing electricity usage to coincide with availability). This is puzzling given that one of Gates’s mentors is the environmental scientist Vaclav Smil, who concludes his recent book Growth with this truism:

‘Continuous material growth, based on ever greater extraction of the Earth’s inorganic and organic resources and on increased degradation of the biosphere’s finite stocks and services, is impossible. Dematerialization – doing more with less – cannot remove this constraint.’

We are faced with a fundamental question, one which Gates does not address: can we repurpose an economic system designed for one thing (generating profit) to do something entirely different (prevent unacceptable harm to the planet and to future generations of humans) without giving up any conveniences along the way? A lot of well-meaning theorists have tried to finesse the contradiction at the heart of that question; Gates is only the latest. But it’s unclear whether the transformation the author proposes is actually possible in the real world on a scale that will truly make a difference. Perhaps something genuinely radical is needed: something more than technology, regulations and incentives; something that would inspire the world – especially the richer portions of it – to give up flying and driving, to live simply, to protect the Earth’s remaining natural beauties, to have fewer children and to forswear consumerism. That may sound naive, but it is about as realistic as Gates’s prescription.

Under a White Sky is, in the words of Elizabeth Kolbert, ‘a book about people trying to solve problems created by people trying to solve problems’. A staff writer for the New Yorker and the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Sixth Extinction, Kolbert is an experienced environmental reporter and an engaging writer. She brings us along on journeys to places where humans have altered nature in sweeping and perilous ways and introduces us to people who are proposing still grander projects – all to control the disastrous results of previous human interventions.

The book is divided into three parts. The first, ‘Down the River’, explores what we’ve done to redirect rivers. In the late 19th century, Chicago’s sewage flowed via the Chicago River into Lake Michigan, polluting the lake and threatening the city’s water supply. In the 1890s, engineers dug a canal that reversed the river’s direction, causing effluent to flow away from the Great Lakes and towards the Mississippi river system instead. One result of this is that the Great Lakes ecosystem is now threated by the invasive Asian carp, which lives in the Mississippi River, having been introduced into the country in the 1960s in the hope it would keep aquatic weeds in check. Imaginative and heroic projects have been proposed to save the ecosystem, including an $18 billion ‘hydrologic separation’ project that would take twenty-five years to complete. At the other end of the Mississippi, New Orleans now routinely has to pump vast quantities of water out of the city to keep it from being flooded. This pumping, however, is accelerating the subsidence of land, making flooding events worse.

The second part, ‘Into the Wild’, reports on extraordinary efforts to stop or reverse biodiversity loss. We meet a rare species, the Devils Hole pupfish, which evolved to live in a singular habitat that’s now being threatened by human activity, and a far more common species, the cane toad, which was imported into Australia in order to eradicate an insect pest (it didn’t) but is now displacing or consuming native species at a prodigious rate. In the case of the pupfish, a new artificial habitat has been proposed as a means of saving the species; with the cane toads, ‘assisted evolution’ via genetic engineering could make them less harmful. Kolbert tries a little genetic engineering herself, using a commercial ‘bacterial CRISPR and fluorescent yeast combo’ starter kit, and learns that it is neither particularly difficult nor expensive, though it could turn out to be ruinous if genetically engineered species have unanticipated harmful impacts (as the cane toad itself did).

The final part, ‘Up in the Air’, explores ways to solve the global climate crisis with negative emissions technologies and geoengineering. The technology to suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere exists and works (indeed, it has already been factored into IPCC future climate scenarios). Yet it is expensive and it is unclear who would pay for it (only a tiny market for carbon dioxide currently exists). Kolbert asks the obvious question: ‘How do you go about creating a $100 billion industry for a product no one wants to buy?’

Geoengineering could take several forms. The one most likely to be tried at scale is solar radiation management through the launching of reflective particles into the upper atmosphere. One problem with this technofix is that it would have to be continued indefinitely: if we failed to keep the atmosphere spangled with particles, a giant bout of global warming would suddenly overtake us. After describing preliminary efforts along these lines and interviewing researchers, Kolbert offers a judgement that could hardly be more fitting:

‘What the technology addresses are warming’s symptoms, not its cause. For this reason, geoengineering has been compared to treating a heroin habit with methadone, though perhaps a more apt comparison would be to treating a heroin habit with amphetamines. The end result is two addictions in place of one.’

While geoengineering could have unintended results on a global scale, it is actually far cheaper than the technological reboot of society that Bill Gates advocates. Our easiest – and, sadly, most likely – course of action will probably be to forgo moderating our consumption and fail to invest enough in low-carbon ways of making our economy operate. Then when catastrophe stares us in the face, we will try to engineer our way out by reshaping planetary systems.

During the last century, technologists exulted in their dreams of mastering the Earth. Man Versus Climate (1960), a Soviet volume surveying proposals to engineer the weather, ended with this declaration:

‘New projects for transforming nature will be put forward every year. They will be more magnificent and more exciting, for human imagination, like human knowledge, knows no bounds.’

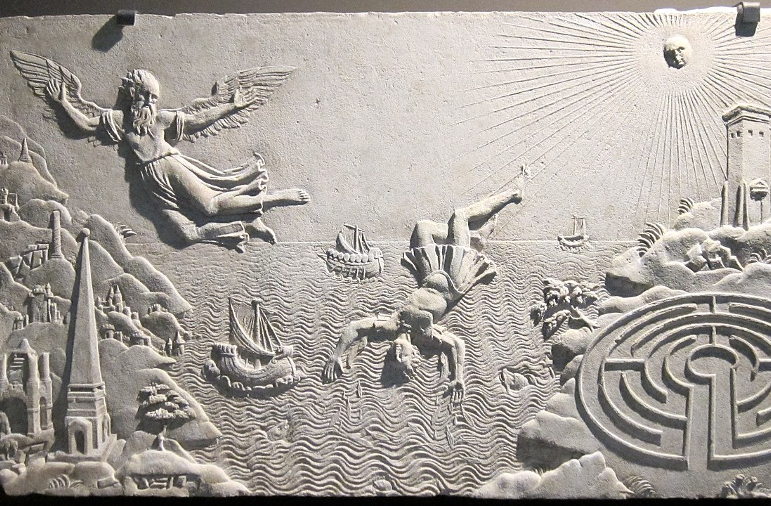

Today our situation calls to mind the myth of Icarus as much as that of Prometheus. Using energy from fossil fuels that we leveraged via rapidly evolving technologies, we have managed to increase our population eightfold, create immense pools of wealth and produce conditions of safety and comfort for billions of our kind. But we have also caused severe, unintended damage to systems that humanity depends on for its continued survival. We can’t seem to figure out ways of overcoming that damage without rejigging nature even more. When will the cycle end? Will it be when we finally get the technology right? Or when nature says, ‘Enough’?

Teaser photo credit: 17th-century relief of the Fall of Icarus with a Cretan labyrinth bottom right (Musée Antoine Vivenel) By Wmpearl – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12147397